Faith and Doubt after Easter

by David E. Anderson

Seeing is believing. Or is it? What about hearing? What about touch?

How does one come to believe what one believes, especially if, on the surface, the claim appears to be preposterous?

Saint Paul put the central declaration — and dilemma — of the new Christian faith in blunt but succinct terms: “If Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14).

Belief in Jesus’ resurrection has been the central and most controversial tenet of Christianity and its core theological principle. Writers and theologians have speculated through the ages on how the resurrection should be understood. Was the risen Christ a body, a ghost, or a spirit?

Some try to glide past the problem by suggesting the resurrection’s symbolic or psychological nature. In his poem “Seven Stanzas at Easter,” the writer John Updike echoes Paul’s insistence on the resurrection’s reality:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle

the Church will fall.

Two recent books take up central questions of faith and doubt in human history. With the rise of Christianity, belief itself became the central religious duty, according to poet and historian Jennifer Michael Hecht in her comprehensive book DOUBT: A HISTORY (HarperSanFrancisco, 2004). Unlike the Romans, whose civic religions were tied to rites, or the Jews, who were bound by Torah and the Law, the early Christians had neither, and instead they focused on belief, says Hecht. “With Christianity, managing one’s doubt, that is, husbanding one’s faith, became the central drama.”

At the same time, Hecht suggests, a new kind of doubt emerged — the believer’s doubt. Jesus himself gave rise to this new kind of doubt, according to Hecht. She points to his anguished prayers in the garden of Gethsemane, when he doubted his ability to do what was asked of him, and the moment on the cross “when he doubted God’s loyalty.”

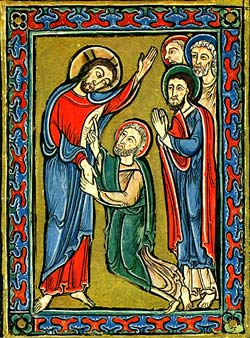

In Christian history, and especially in the Easter story, no one has symbolized the so-called “believer’s doubt” more than Jesus’ disciple Thomas. He has become such a paradigm of the kind of doubt that assails the faithful that the very quality has been attached to his name, and he has come down to us not as one whose doubt was resolved in faith and belief but as Doubting Thomas.

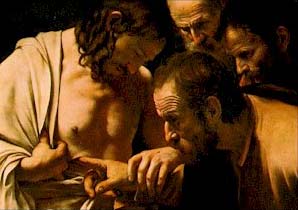

In his book DOUBTING THOMAS (Harvard University Press, 2005), University of Chicago professor and ancient Greek specialist Glenn W. Most gives a close reading of the Thomas story as it appears in the Gospel of John. Most also probes the question of belief in the resurrection stories of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and he examines the way the Thomas story has been interpreted and developed over the centuries, focusing with special insight on its visual depictions, particularly Caravaggio’s famous painting of Doubting Thomas.

For many readers, the most startling claim in Most’s analysis is that Thomas never actually touched the wounds in Jesus’ hands and sides, despite centuries of both homiletic tradition and the visual tradition represented in the artworks of Caravaggio, Rubens, and many others. The crucial verses are John 20:27-28:

Then he (Jesus) said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing.” Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God.”

“This is the first time,” Most notes, “in the whole of John’s Gospel, or in fact in any of the New Testament Gospels, that anyone calls Jesus a god, let alone to his face.” But Most argues that readers who believe Thomas’s startling outcry follows from touching Jesus are mentally supplying a sentence or a thought that is not in the text. For Most, John’s use of the word “answered” rather than some expression such as “said” or “exclaimed” is crucial:

The grammar of the verb used here … is unambiguous: it occurs more than two hundred times in the New Testament, and whenever it introduces a quoted speech B spoken by one person that follows a quoted speech A spoken by someone else, then speech B is a direct and immediate response to speech A, not to any other event intervening between the two speeches. That means there is no room between Jesus’ speech and Thomas’s speech in which something else — the touching of the wounds — could happen that might spark Thomas’s exclamation.

“Thomas’s attempt to found religious faith upon the empirical sense of touch fails utterly: to suppose that Thomas might actually have touched Jesus, and thereby have been brought to belief in his divinity, is to misunderstand not just some detail of John’s account, but its deepest and most fundamental message,” Most writes.

To underscore his point, Most notes Jesus’ reaction to Thomas’s confession: “Jesus said to him, ‘Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.'”

Even if seeing has once again become believing, it is not the highest form of belief, Most contends. That belongs, as Jesus says, to those who can believe without seeing. Here, according to Most, Jesus is following the Hebrew Bible, “which in general privileges that faith which is based upon hearing God’s word alone over any requirement that that belief be attested by miracles.”

Most tracks the way the Doubting Thomas narrative was shaped and retold in the early church, especially in the apocryphal books that didn’t make it into the New Testament. He spends some time on the Gnostics, who viewed Jesus’ resurrection as purely spiritual, not material, and who thus developed a minor tradition of interpretation that said Thomas did not actually touch Jesus. The anti-Gnostics, however, insisted on the materiality, the corporality of Jesus’ resurrection, and that has been the mainstream Christian tradition, from Luke’s insistence on having Jesus eat fish to show his apostles he wasn’t a ghost to Updike’s insistence that the resurrection was “not as the flower” but “it was as His Flesh: ours”:

The same hinged thumbs and toes,

the same valved heart

that — pierced — died, withered,

paused, and then

regathered out of enduring Might

new strength to enclose.

It was only with the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, Most writes, that “a new and quite different interpretation of the story of Doubting Thomas became possible” because of the reformers’ willingness “to put into question the millennial view that Thomas touched Jesus.” For her part, Hecht notes that “doubt in Europe in this period was about doubt in the Church,” but it was also about a mood influenced by Renaissance humanists such as Erasmus. The humanist-inspired Reformation theologians’ principle of “Scripture alone” and their disdain for ancient apocrypha as well as centuries of interpretative commentary; their privileging instead of Jesus’ spoken words; and their reliance on the touchstone of “faith alone” rather than on what Thomas did or did not do all allowed them to question the long-held view that Thomas touched Jesus.

Nevertheless, Hecht observes, “doubt was not Luther’s cup of tea,” and Catholic counter-Reformation theologians were “no less convinced than their pre-Reformation predecessors were that Thomas did indeed touch Jesus — indeed, they seem to be far more stridently so.”

One of Most’s innovative contributions to the Doubting Thomas tradition is his study of pictorial versions of the story. Until the invention of the printing press, the church often used pictures and other visual arts to mediate between the written text and communities of illiterate believers. Taking Caravaggio’s painting as a starting point, Most suggests that the message of the many images depicting the Doubting Thomas story is at least in part directed at the viewer. “Thomas,” Most writes, “both does and does not represent us: we must strive to be as like him as possible in certain regards and as unlike him as possible in others.”

But there is a paradox in the paintings of Thomas inspecting Jesus’ wounds. The pictorial images “must try to persuade us to believe in Jesus’ resurrection by permitting us only to see, and not to touch, an image of someone who achieved notoriety for claiming that seeing is not enough and that only touching provides real proof.” Most concludes that Caravaggio’s painting is a representation “neither of faith nor of doubt, neither of religious belief nor of scientific skepticism, but rather the irreconcilable conflict and the indispensable interdependence between them.”

Echoing Hecht’s exhaustive history of the many forms doubt has taken and continues to take, Most concludes, “Many of us cannot live without doubt any longer and cannot even imagine what a non-skeptical life would be like.” Yet, he adds, “We are all failed skeptics. For those of us who are Christians, Thomas is an emblematic figure: he has expressed a doubt from which even the most pious believers cannot be entirely free at every moment of their lives, yet he himself has overcome this doubt once and for all. But he is emblematic too for those of us who are not Christians: his doubts are our doubts, and his inconsistencies are our inconsistencies.”

David E. Anderson is senior editor of Religion News Service. He last wrote for RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY on “The Torture Debate”.