LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: When Mark and Jennifer Drago decided to get married, they had both drifted away from their separate churches. He was a Methodist, Jennifer a Lutheran. So they asked Pastor April Gismondi of the non-denominational Church of Ancient Ways to officiate.

PASTOR APRIL GISMONDI: On this area of Long Island, a lot of people of a lot of different religions come together and agree that spirituality is the core of the human belief, not the book you got it from.

SEVERSON: And then two and a half years later, when their daughter Julia was welcomed into the world in another ceremony, Pastor Gismondi spoke the words and wisdom of one of the most popular poets of all time, and among the most controversial — Kahlil Gibran.

GISMONDI: (Reading from Gibran) Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself. For you are the bow from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.

He speaks to the core of what makes us truly human - the things that we all struggle with, the things that we all enjoy, the lessons we have to learn.

MARK DRAGO: He has this metaphor with the arrow, which I think is great.

JENNIFER DRAGO: They’re ours but they’re not ours to keep. Like we get to have them for just a little bit of time, and then we have to send them off.

GISMONDI: And it’s so eloquent. It really is.

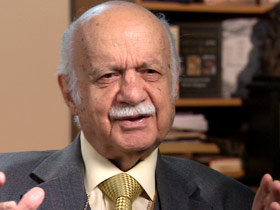

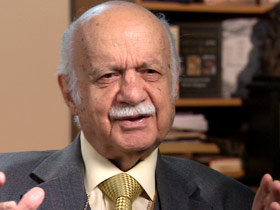

SEVERSON: Apparently millions of readers agree. Kahlil Gibran is one of the best selling poets of all time, behind Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu, the founder of Taoism. Suheil Bushrui holds the Kahlil Gibran Chair for Values and Peace at the University of Maryland.

SUHEIL BUSHRUI: I’m not saying that Gibran is as great as Shakespeare, but I’m saying that people who have a universal message, Goethe, Dante, Shakespeare, the great poets of all time, because of their universal message, they resonate with every culture, every language and every people.

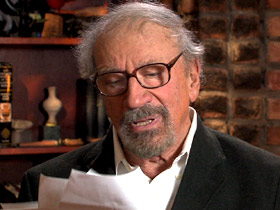

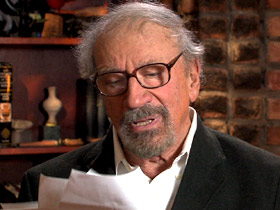

SEVERSON: Gibran’s widespread and lasting popularity has also been greeted with much critical derision. Among the critics who least appreciate the poet is Stefan Kanfer.

STEFAN KANFER: His work has always seemed to me, Khalil Gibran’s, like halva — which is a part of Middle Eastern cuisine which is almonds and honey — to the point where you really can’t take more than a little bit of it. And sometimes I feel if you read enough of this kind of stuff, your appetite for real food goes.

SEVERSON: He gives numerous examples of what he calls Gibran’s “muzziness,” and pseudo-paradoxes.

KANFER: Here he is on marriage. This, by the way, from a man who never married. “Fill each other’s cup but drink not from one cup. Sing and dance together and be joyous, but let each of you, each one of you be alone even as the strings of a lute are alone.”

BUSHRUI: This is, this is mysticism. This is that other level of communicating.

GISMONDI: He says that joy is sorrow unmasked. He talks about how if you’re sitting at your table with sorrow, joy is in your bed waiting to awaken.

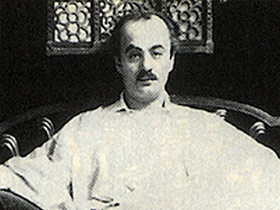

SEVERSON: Khalil Gibran was born in 1883 in Northern Lebanon, and grew up in a poor, Maronite Catholic family. Priests tutored him about the bible, but he had no formal education. After his father was imprisoned for embezzlement, his mother moved the family to Boston, Massachussetts.

LIESL SCHILLINGER: He arrived with his family as a 12-year-old immigrant, living in the slums of Boston, the Syrian quarter. And by the time he was 13 or 14, he had already been discovered.

SEVERSON: Liesl Schillinger is a New York literary critic, who contributes to several major publications.

SCHILLINGER: He has a beautiful face and he is said to have had an arresting and mystical way about him. People felt they were talking to a prophet. And he went pretty quickly from being this teenager to having his own verse published in various quarterlies.

SEVERSON: Gibran had help along the way, as he grew into adulthood — usually from women.

SCHILLINGER: It’s true that he admired women and many of them admired him. You know, this is a handsome man who speaks of love, who speaks of individuality who respects women in his writing as humans.

BUSHRUI: Now the most important influence of course came from Mary Haskell, a schoolmistress ten years his senior, who detected in this young man something very special. So she arranged for him to go to Paris. She funded him.

SCHILLINGER: She had enormous faith in him. She very nearly married him, but decided that at the time it would have hurt her social standing too much because at that time, that would have been considered a mixed marriage.

SEVERSON: By far Gibran’s most famous work was "The Prophet," a short 20,000-word collection of prose and poetic essays, written when he was in his twenties and thirties — and then living in New York City. He would compose poems sitting on a bench looking out at the Statue of Liberty.

BUSHRUI: The Statue of Liberty, America itself, of course has its shortcomings as well, but he saw it as the hope for the world.

SEVERSON: And he expressed this hopeful attitude in both fluent English and Arabic. "The Prophet" has been translated into over 40 languages.

SCHILLINGER: He helped present an appealing mystical idea of the wisdom of the East. He was someone who helped humanize and popularize Eastern thought.

SEVERSON: In Stefan Kanfer’s view, it’s remarkable that Kahlil Gibran’s work achieved any kind of influence.

KANFER: I don’t think he’s a phony. I think he genuinely believed in what he believed, but it’s it really is, um, simple stuff.

BUSHRUI: It uplifts my soul and teaches me something to think about, well, that’s good enough for me. Yes, there has been enormous criticism sometimes, and very bitter criticism against him, but the question here is which of the great poets, or figures in history, has not been subject to the same degree of criticism.

SEVERSON: But Kanfer doesn’t consider Gibran one of the great poets.

KANFER: And here he is on death. “When the Earth shall claim your limbs, then you shall truly dance.” Well, is this the afterlife? Is it Christianity? Is it Buddhism? He uses this kind of indistinct manner of speaking.

SCHILLINGER: People who read his poems can find in them resonances of Sufi-Islam. They can find resonance of Hindu love poems and life poems. They can find resonances that sound like, that are biblical as in from the King James Bible.

SEVERSON: When "The Prophet" was first published in 1923, it was not an immediate or complete success. Critics panned it, but the public bought it. Then sales flagged until the Vietnam era.

BUSHRUI: There was the Vietnam War, the disappointment of the youth of America. What could take place to help find the meaning in life? Gibran. "The only thing you need is love." This is what Gibran is saying, but it is not sexual love that he’s talking about. He’s talking about loving human beings, loving humanity. Yes, he filled the gap that was necessary to be filled. It was a spiritual gap.

SEVERSON: A building in Lower Manhattan that once was Gibran’s home and studio. Today it’s a place of pilgrimage for those who feel his words still speak to them. But reverence is relatively rare among today’s literary elite. After Liesl Schillinger’s assessment of the writer, one of his family descendants wrote her expressing surprise that she had treated Gibran so "unscornfully." She says he doesn’t deserve scorn.

SCHILLINGER: He has existed as a bridge between the Middle East and America and the Western world, a bridge between Christianity and Islam to help people around the world to feel their commonality.

SEVERSON: Khalil Gibran died when he was 48, in 1931. To date, it’s estimated that "The Prophet" has sold more than 100 million books worldwide, nine million in the U.S. where it’s never gone out of print.

For Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson.