JOHN DANCY: Although a recent Gallup poll indicates support for the death penalty is the lowest in 19 years, 66 percent of the people responding said they favor capital punishment.

Imagine the sadness of dying alone. To that dismal prospect, add the thought of dying alone in prison. Well, not long ago, one of the toughest prisons in the country created a hospice program to ensure that that doesn't happen to its inmates. Lucky Severson reports from Louisiana.

LUCKY SEVERSON: From a distance, this sprawling, gated compound on 18,000 green acres could appear to be a country club, but Angola is not a country club. It is a prison for what the Louisiana justice system has determined to be the worst of the worst -- robbers, murderers, kidnappers in that category.

Angola has been known over the years as the biggest and baddest in the U.S. It is still the biggest maximum-security prison by far -- 5,108 inmates, all men -- but it's doing its best under Warden Berle Caine not to be the baddest.

Mr. BERLE CAINE (Warden): When I came here and saw the first funeral, when they took him down there and dug a hole with a backhoe and put him in a cardboard coffin and put him in that ground and threw the dirt in and the top collapsed in on it, and one fell through the bottom of the cardboard coffin, I said, "Enough is enough."

SEVERSON : The prison cemetery is neat and well groomed, but most of the inmates interred here were buried in cardboard boxes. And it is not a quiet resting place. You can hear the sound of gunfire at the firing range 100 yards away. This is not a country club. These cadets are shooting at targets the same as they will any of the inmates who try to escape. Very few do.

Because only the worst criminals end up here, with long, often life, sentences, most die of disease or old age. But now when they die, they're put to rest in proper wood coffins made by fellow inmates. Warden Caine considers himself a religious man with a forgiving spirit ...

Mr. CAINE: Are they taking good care of you?

Unidentified Inmate #1: Oh, yes, sir.

SEVERSON: ... but only after a convicted felon has paid his price to society.

Mr. CAINE: I think he should die with dignity. I feel great compassion for the victims, but I couldn't be there with the victims. I am in control of this, and so I'm supposed to do right by what I can control and do right with.

SEVERSON: Angola is known as the end of the road for good reason. Eighty-five percent of the inmates who end up here, die here. And until a couple of years ago, they were often lonely, wretched deaths. That was before Angola started a hospice program two years ago, where inmates who would normally be under lockdown are allowed to take care of other inmates who are dying. Alvin Royal has full-blown AIDS from a heroin needle. He was convicted of forcible rape, armed robbery, and second-degree kidnapping.

People help each other here.

Mr. ALVIN ROYAL (Inmate): Oh, yes. Yes. We got as much love than we had out there on the street when we was shooting each other, robbing them, stabbing, you know, killing and raping.

Unidentified Inmate #2: It's a blessing to be able to do what we do here.

SEVERSON: There are six inmates dying here. Sometimes each has several helpers, sometimes only one, or at least a favorite. Warren Martin has Lou Gehrig's disease.

Mr. WARREN MARTIN (Inmate): I feel pretty good.

SEVERSON: Now you got this guy here, Arizona.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, that's my hands and feet -- everything.

SEVERSON: And, Arizona, what are you in prison for?

Mr. ARIZONA SHULARK: Second-degree murder.

SEVERSON: Arizona is here for life, and in Louisiana, life means life. Parole is very, very rare.

Mr. SHULARK: I'll leave here the day I die. You spend most of your life -- man, the only thing you got going for you is whatever you can take from somebody, and then all of a sudden you find yourself getting something, giving something and not wanting in return. That's a blessing to me because I ain't never known what that even meant, and I've got some of the best things, my patients' love.

SEVERSON: Arizona decided to get involved in hospice after he saw a friend suffer a painful death with no one to look after him.

Mr. ARTHUR RHOADES: It certainly give you a lot better care to have a hospice, because you wouldn't get any care if it wasn't for the hospice.

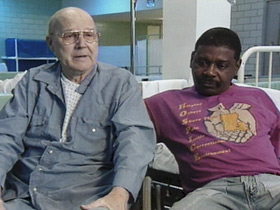

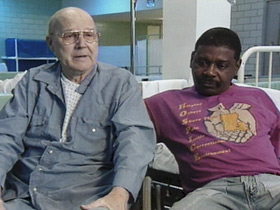

SEVERSON: Arthur Rhoades was a physician, a general surgeon sentenced to 22 years for growing marijuana. He said it was for his wife, who was suffering from cancer. Rhoades is now himself dying from emphysema. His helper is Ralph Dawson, in for life.

Mr. RALPH DAWSON: It was a simple robbery gone bad. I tried to take a man's car. I was drunk and I was high on drugs, and I just started beating on him and couldn't quit.

SEVERSON: Angola may be the only prison hospice program where inmates act as helpers. Normally in other prisons, the helpers are trained civilians.

Mr. DAWSON: When it's inmate to inmate, there's an element there that is different than if it was free society with an inmate. That element is that I live here and I know what he's going through because I go through it myself.

SEVERSON: And so inmates in prison for serious crimes against society who have never cared for anyone but themselves care for each other and become family.

Mr. DAWSON: He's just like a grandfather to me, you know. I come to him, talk to him, get some wisdom from him.

Chaplain CHUCK SMITH: We thank you, gracious God, for our brother and for his faith that you have given him.

SEVERSON: Presbyterian chaplain Chuck Smith says he is drawn to this place, more so than the two churches he also ministers on the outside.

Chaplain SMITH: The only thing that I can bring to it is a little bit of expertise by training and by experience. But you have to insert that very gingerly, because they're very protective of one another.

SEVERSON: There is a sense of spirituality here, the quiet kind. This is a graduate of the prison's Bible school sharing what he has learned with a man who knows he is about to meet his maker.

Mr. CAINE: It makes the prison more stable because they learn to care for one another. It sends a message to everybody: Love your neighbor, you know. And even in the Scripture it says the last commandment was, "Love your neighbor as yourself."

Mr. ALBERT RICHARDSON: I don't know why that fellow inmates would look out and care for one another like they do, you know.

SEVERSON: Albert Richardson, second-degree murder, paralyzed from the waist down from cancer. His helper, Claude Donald, convicted of armed robbery.

Mr. CLAUDE DONALD: I come up selfish, nobody -- thinking about nobody but Claude, you know, most of my life. And the first guy I ever bathed -- when I got through bathing him and got him back in his bed, he told me, "I appreciate that." And it just did something to me.

Mr. RICHARDSON: I kept telling them that -- I said, "Man, I hate it. I hate to be in this shape for you to do this." And he said, "Oh, man, there's just nothing to it. We don't mind it. We don't mind it."

Chaplain SMITH: I have seen people here, not just in hospice but certainly in hospice, become human beings. One does not think of a prison [as] a place where one comes to one's humanity, but that's certainly the case here, because people come here hardened or heartless, without feeling at all. Somewhere in the process, they open and change.

SEVERSON: The number of Angola inmates 65 and older has doubled in the last 10 years, so there is an increasing need for this program, one the National Prison Hospice Association says should serve as a model for all other prison hospices. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Lucky Severson, Angola, Louisiana.