In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

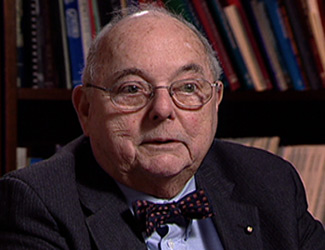

Interview: Dr. John Collins Harvey

Read more of the R & E interview with Dr. John Collins Harvey, who chairs the bioethics committee at Georgetown University Hospital:

Dr. Harvey, describe what it is the bioethics committee does with families.

The bioethics committee is mandated by the accrediting council for hospitals. It is set up to be a helpful advisory only — not decision-making — group for families, physicians, nurses, and social workers if an issue comes up in the care of a patient that falls into the field of medical ethics, nursing ethics. Very often, a conflict between a family and the physician or between the physician and the nurses taking care of a patient regarding the good and right thing to do for a patient is brought to us. We try to get the group together, sit down and go over the issues, and try to bring some resolution and advice to the group. The ethics committee members do not ever make decisions for individual care. They simply bring together the groups that consider all of the various issues around which the disagreement is occurring.

As both a moral theologian and a physician, do you make a distinction between keeping someone alive on a respirator and keeping someone alive on a feeding tube?

No, and that’s a very misunderstood thing. What’s important to understand is certain illnesses cause pathological conditions so that an organ system does not work — let’s say kidney disease, and certain kidney diseases will destroy the total function of the kidneys in the body. We can substitute now a machine that does the physiological work of the kidneys. That’s renal dialysis machines. And people with kidney disease who would otherwise have died can remain alive being dialyzed maybe two or three times a week and they can go on, for many years, living.

The same situation occurs when people have difficulty breathing. We have a machine that will breathe artificially for somebody. So we put a tube down their trachea, attach it to the machine, and it will do the breathing for them. We have the ability to have an artificial heart that will do the work of the normal heart when the heart has failed. The point is that if you can do, substitute the physiological mechanisms artificially for those that have failed, we use that. If the situation is a fatal, pathological condition that can never, ever be overcome, then one has to look at the boons and the benefits of this artificial, physiological mechanism.

Why is a feeding tube, in your view, the same as keeping someone alive on a respirator or through dialysis, and not elementary comfort care?

Because if it’s being done where there’s fatal pathology, it is just as if you were using the kidney machine on somebody who has no kidneys. They can stay alive, but if they decide that they don’t want to undergo this, it’s too much of a burden, it’s perfectly moral to stop.

When somebody has a condition in which they can never bring food to their mouth by use of their arms; they can never chew food if it’s placed in their mouth, because the muscles of mastication are paralyzed; if they can never move the bolus of food that they have put in at the front of the mouth and then moved by the tongue back to the esophagus, where automatic peristalsis takes place, and down the food goes to the tummy and then is absorbed and whatnot — if that is a fatal pathology that they never will recover, the ability to chew and swallow, then if we use administration of food and fluid artificially, we’re prolonging biological life. We’re not prolonging an individual to where cure can take place, and then we remove that artificially administered fluid. Just because it’s such a simple machine, such a simple tool, it makes it no different from a respirator, from an artificial heart, or from kidney dialysis machines.

The best way I can explain that is if an individual has what we call a tetanus infection, which is caused by a bug, an organism that grows in a small wound anyplace on the body, and it produces a poison, tetanus toxin, and the tetanus toxin affects all the muscles of the body, but particularly the muscles of mastication. It’s known as “lockjaw,” because as it advances, it makes the mouth clench. The body is stretched so that the person forms an arc because the back muscles are very tense and tight. We can treat the wound where the bug is growing and putting tetanus poisons into the system by antibiotics, like penicillin. Over a period of a month, we can get rid of that wound, overcome the infection; and the effects of the toxin gradually wear off, so that the individual will be able to recover fully the ability to eat normally. If we did not use a tube to feed that individual during this time of terrible physiological defect, he or she would die, because they would get no nutrition. So it would be mandatory to feed this type of individual.

But in the persistent vegetative state, there is no hope ever of recovery of this normal physiology of eating, swallowing, and giving food to yourself.

What is “fatal pathology,” in the medical view?

It’s a pathology brought about by a disease process that can never be cured and is going to ultimately lead to the individual’s death.

How do you decide that someone is truly in a persistent vegetative state?

We know the ability for an individual to express what we call his or her personhood — to love, to think, to remember, to talk, to move is all done by the biological substrate in the brain called the cerebral cortex; that’s the upper part of the brain. The lower part of the brain controls the vegetative activities of the body, like making sure the heart is beating at its given time, that we’re breathing regularly, that the kidneys are making urine, that the bladder is being able to fill it up and then expel the urine through the urethra. These are all vegetative activities in the body which we’re not even aware of.

The cerebral cortical cells and the vegetative area of the brain — if they are deprived of oxygen for given periods of time, they will die. The cerebral cortical cells can only tolerate the lack of oxygen for about six minutes, and then they die. And the death is irreversible, and no new brain cells ever grow up. Over a period of time, the cerebral cortex degenerates, disintegrates, and it just becomes in the skull kind of a bag of mush. The vegetative cells in the lower part of the brain can withstand the lack of oxygen for 40 to 50 minutes, and they will continue to function.

All of the cells of the body can be deprived of oxygen for different periods of time. The fingernails, for instance, can still metabolize and whatnot without being supplied by oxygen for a period of 24 hours. The kidneys also can work deprived by oxygen, so that very often people that are pronounced dead because their heart stops and their respiration stops — the bladder will be filled, will have urine accumulated in it after death has been pronounced because the kidneys are still doing a little work. The death of cells is at a different time rate after oxygen has stopped being circulated, which means the heart has stopped beating and the lungs are not aspiring so that oxygen is supplied to the blood. In the persistent vegetative state, the individual has been without blood going to the head for at least six minutes, so the cerebral cortical cells have died. How does this come about? It comes about because the heart stops beating. The heart can stop beating from a heart attack, from a coronary occlusion. The heart can stop beating if the individual is electrocuted by lightning on the golf course. The heart will stop beating if the individual is drowned. And sometimes, the heart will stop beating when there’s a terrible severe trauma to the head. The heart does not stop beating when an individual is poisoned by drugs and is put into a permanent coma by a drug, like the Quinlan case. Severe trauma does not always make the heart stop, but it can discombobulate the cells of the cerebral cortex, so that we see people who are in coma for 10, 15 years, and very rarely you will hear they woke up one day. That’s because they are not in the persistent vegetative state, because they did not have cessation of oxygen going to their brain at any time during their illness. But individuals who have had that, and the oxygen has not gotten to the brain over that period of time that I described — they are never going to recover, because they do not have any brain cells to recover. Brain cells that are discombobulated by drugs, alcohol, or by a trauma — their physiology is just disrupted, but maybe over 20 years it finally returns to normal.

Does it always happen that way? Are there exceptions to the rule?

Well, I do not think that we can talk about people who appear to be in the persistent vegetative state where we know that their heart has not stopped beating. But if I know that the heart has stopped beating, that the heart was started up at the scene of the accident by the emergency medical technicians, who can revive individuals now, get their heart going, get them reanimated — if we know that the heart stopped beating, and they develop this what we call “wakeful coma,” which is a persistent vegetative state, we know they’re never going to recover.

If the history is one of drug intoxication, or trauma, where there’s no record that the heart has stopped beating, then I do not think that we can say that’s the persistent vegetative state. That’s persistent coma. I think we have to be careful about withdrawing food and fluid from those people.

Was Hugh Finn, in your view, in a persistent vegetative state?

Yes. Yes, he was, because I think it was very clear in his medical history that at the time of his accident, his heart had stopped beating. And the emergency medical technicians at the scene of the accident revived his heart, so it started beating again, and he started having respirations.

What do you say, as an ethicist, to the family that just will not give up hope, even given the medical facts, that their relative will come out of this, will recover?

You give them the medical facts that their relative can never recover if they’re in the persistent vegetative state, and so doing these things is futile treatment. As a physician, I could not ethically give futile treatment to a patient. That’s wrong.

What do you say to the family that will not remove that tube?

I would talk to the family very carefully, point out all of the issues, and then say, “You know, I, in conscience, cannot continue this treatment because it’s futile. The individual is dying.” The burdens of such treatment are so great, compared to the benefits — the benefits are maintaining purely biological life. I would say to that family, then, “I can’t continue to be your doctor because I do not believe you’re doing the right thing by this patient. I think it’s poor medicine. It’s a poor way of treatment. And I feel I’m a good doctor and try to do the best for my patients.”

Now, this is purely the medical aspects of things. I’m not talking anything now about the moral aspect. This is if any patient came to me, regardless of his or her religion, and insisted that we continue feeding a person in the persistent vegetative state as I have defined the persistent vegetative state. If they would not follow my medical advice, I would have to ask them to find another doctor to take care of their patient, which is the correct way physicians deal with individuals. You never abandon a person, but you help them find another doctor who will work the way the family wants.

You’ve given the point of view of a medical doctor. What about a religious point of view? What would you say to the family that says, “We cannot do this. It is against our religious beliefs and moral beliefs”?

I happen to be Roman Catholic, so I’m very interested in the question. From the religious standpoint, from the moral standpoint, in our Roman Catholic belief, it has been a teaching of the Church for the last 500 years that when treatment is futile, it is not required to be given. When an individual is dying and we inhibit that dying process, if we stop inhibiting that process it’s perfectly moral. It’s perfectly licit. It’s perfectly compatible with the Church’s teaching. This is what is very misunderstood by many families of patients in the persistent vegetative state. The teaching of the Church, perhaps, is not well understood by these people. But from the moral theologians of the 16th century, 17th century on down to the present time have all pointed out that when there is a fatal pathology, we are not obligated to maintain simply biological life; because the biological life, while it’s a great human good, is not the ultimate good, not the “telos” of why we were created. We’re created to live in glory in heaven with God. And if we maintain biological life that can never recover, we are prolonging the ability of that individual to reach his or her final end, which is life in heaven in glory with God.

Could you say more about keeping the whole person alive?

When the individual is in the persistent vegetative state or in wakeful coma, we know that that individual can never, ever, express his or her personhood again. He’s still a person beloved of God and precious in God’s sight. There’s no question about that. But he or she is never going to be able to express their beliefs, their adulation to God as a creature here on earth. And all we’re doing is maintaining that individual in a biological state. That biological state, if it’s not treated, is going to die. It’s a heresy of vitalism, keeping somebody going when we’re preventing them from reaching God, which is their final end of their life. We’re keeping them from God. The Church teaches that we’re not required to do that. It’s basically wrong.

What do you say to those who believe that a feeding tube is really comfort care, elementary care of a person; it is not an extraordinary measure.

But it is an extraordinary measure because of the fatal pathology. Many individuals who insist it is comfort care simply do not understand the complexities of which I have been talking. And many of these people are very adamant and very zealous in their insistence, but they just have not understood the teachings of the Church with these nuanced kind of changes.

How have ethical questions changed over the years because of medical advances?

Medical advances in all fields have created many, many ethical problems that we never faced before. Absolutely. The kidney dialysis machine keeps people alive, but they’re able to stay alive expressing their personhood, not just maintaining a biological life. And yet, the burdens of that on some people are so great that they decide they don’t want to have this treatment anymore, and they stop it. Some people would say, “Wait. You can’t stop that. You’re committing suicide if you stop the kidney dialysis.” Not at all. The Church never says that. The Church says if the burdens of this treatment are so great for you, for the reasons you give, that you decide you do not want this which is life-saving and keeps you going — if you decide to stop it, and you do and you will die within a week, you have not committed suicide at all. You have decided that extraordinary treatment is not for you. And the Church has taught all the way through — the best example of that is Pius XII’s elocution to Dr. Bruno Hyde in November of 1957 at the Vatican, when the anesthesiologists, meeting as an international group, asked him, “Is it licit to withdraw a respiratory tube artificially keeping somebody alive if, when you do that, the patient’s going to die?” He said, “Absolutely, because that’s extraordinary care and it violates the natural end of a human being. It’s interfering with the human being going to God.” The best example of what you would want is the woman or the man with kidney dialysis who’s fully conscious, fully responsive, fully able to make decisions.

You’ve spoken a number of times about the Church’s teaching being very clear, but in fact, you have a group of bishops in Pennsylvania saying one thing about this, and a group of bishops in Texas saying another thing. It seems there isn’t a clear-cut guideline from the Catholic Church, or any church, on this.

The committees of bishops in different states in this country have issued various statements and, indeed, what you say is quite true, that the bishops in Pennsylvania, speaking as a conference, have said, in their opinion, that the teachings of the Church would demand that the feeding tube be kept in, except in the most dire circumstances, where death is imminent from other causes. But when you go further west, the bishops’ conferences have not maintained this attitude and have said it’s perfectly licit to withdraw the feeding tube. The bishops are certainly the teachers of morality to the faithful, and they teach the principles. But underneath the principles there have to be considerations of the individual cases, the nuancing of the general principle based on the circumstances of each individual patient’s illness. And this is what a lot of people do not seem to understand. The Church teaches through its bishops, but the final authority of the teaching is either a council or the pope speaking ex cathedra. And none of that has been done in regard to use or disuse of feeding tubes, so that there is no official, immutable teaching on this point. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has issued its declaration on euthanasia, and it touched upon the removal of feeding tubes under certain circumstances. It said we should always presume in favor of maintaining life, but there are circumstances where the burdens outweigh the benefits and the feeding tube can be removed. The teaching has never been authoritatively defined so it’s a final, absolute teaching. That’s why you get these different opinions of the different bishops’ conferences, of different priests, of different physicians.

When a family is making a decision to put in a feeding tube, what types of considerations should go into that decision?

I think the diagnosis has to be quite clear. In my opinion, the way I treat patients, I would never consider taking a feeding tube out of anyone who was in permanent coma or who developed, then, the wakeful coma that is fairly characteristic of the persistent vegetative state. I, personally, would not even talk about removing it until a year had passed.

Why is it such a turning point, putting that tube in?

Well, it’s not a turning point. We use it all the time for pathology that prevents somebody from taking in food. It’s perfectly good and useful and mandatory care, as I said. If somebody has tetanus infection, you would be committing a mortal sin, you would be committing a felony against that person if you did not use a feeding tube.

What about cases where there has been some deprivation of oxygen to the brain?

If the history is so clear as that would be, then I would, after six months, when they’re in the persistent vegetative state, feel it’s perfectly okay to withdraw the feeding tube.

But what about putting the feeding tube in, to begin with?

I would never not put the feeding tube in, because I think it’s one of those things that you never know. A miracle may occur. The individual may wake up. We may have made a misdiagnosis. The heart may not have stopped, but people thought it did.

Is there a time that you would say, “Well, we should give up hope at this point”?

A year. Absolutely.

How expensive is it to keep someone alive on a feeding tube?

It’s about $60,000 to $80,000 a year.

How do you weigh the costs and benefits of this?

The cost-benefit is entirely moral to consider; that is one of the burdens that the family or the community is bearing. And if the community feels that it can’t afford that benefit for patients in Medicare, or if a family feels, with its private funds, it has a limited amount of money to send the grandson to college or to keep Grandma alive in a nursing home in this futile situation, the cost can be considered a burden. The psychological burden of the family, the terrible psychic trauma of seeing this individual, their loved one, lying in this condition for over a year is very, very costly on the psyche of family members. That can be brought into consideration. Pius XII said that. Gerald Kelly, a great Jesuit priest who was a great medical moralist, said that way back in the ’50s.

Given the huge costs of keeping someone alive on a feeding tube, do you think families might be susceptible to pressure to remove their family member from the feeding tube in that case?

I can give you an instance of that. There was a family that had just such a situation. The patient was transferred to a nursing home, and the individual’s insurance provided for something like four or five months’ care in a nursing home, which most hospital insurance doesn’t provide for chronic care. They were insistent that the tube be kept in until they found they had a burden to keep it in — namely, $60,000 a year.

Would it be moral to remove it in that case, when money is the only burden? Is cost a valid moral basis upon which to make your decision?

Cost is a burden. The moralist Gerald Kelly and Pius XII both said that extraordinary burdens do not have to be borne by patients or families or communities, and cost is a burden to be considered in maintaining an individual in a persistent vegetative state with a feeding tube.

Why did you intervene in the Hugh Finn case?

I was called by the attorney who was representing Mrs. Finn, and he asked if I would testify for them on the medical aspects of persistent vegetative state. I never met Mrs. Finn. I had no contact with the patient at all. I was simply asked to talk about, what is the persistent vegetative state? How does one describe it? How do we treat individuals in a persistent wakeful coma, and what would the outcomes be under different circumstances?

Knowing what you know of the details of his case, you concluded that she was absolutely proper in her decision?

Yes, I felt she was right.

Did you feel it was clear-cut that he was in a persistent vegetative state?

There was no question about that. I never examined him, but from reading what people reported, there’s no question. The nurse who was an expert in public health nursing and said that, when she went to visit him at the insistence of the state health department when the governor and the state representative intervened, she thought he was talking — this is not talking. Individuals in the persistent vegetative state have reflex actions, including reflexes that will end up in groans and noises that are meaningless, but are there.

A Virginia delegate who also was involved in the Hugh Finn case made the point about doctors trying to play God, relatives trying to play God — that doctors are no longer following the Hippocratic Oath. How do you respond to that?

That’s out of pure ignorance that he is saying something like that. Doctors are still very moral. They’re still following the Hippocratic Oath. They’re doing the very best they can by their patients. We all know that medical progress and high technology have brought these problems that were never dreamed of 50 years ago or 25 years ago. I do not think politics has a place in medical treatment.

How about government intervening in these cases?

I do not think government should intervene. If the physician is doing the best he or she can do, is following the best medical, moral practices, I do not think there should be intervention in the doctor-patient relationship. That does not mean that people can do things that are illegal. But I’m just saying that a very excellent doctor who’s following his or her best ability to give the right care to an individual, following all that we’ve been taught from both the physical, scientific and moral standpoint, should not be interfered with by outside bodies.

If you were making the decision to remove the feeding tube, could you tick off some of the points that people should look at?

How much nursing care is required? Is it taking nursing care from other people who need it and would benefit by it? And there are physical and medical complications which are a burden that an individual would not be forced to undergo. Then you have to think of the burden to the family next. Is the terrible psychic trauma that can occur — the disruption of normal family relationships, with fighting going on between different members of the family arguing “yes,” “no,” “yes,” “no,” can be terribly disruptive and destroy a whole family this way. The psychological burden on the family, the financial burden on the family. And then the financial burden on the community. When you spend $60,000 a year on taking care of somebody and the care is not going to bring them back to a cognitive life, but merely maintain biological life, is it wise, if their community resources are of a given amount, to use them this way, or to use them for benefit of many more people in a different way?

When you say the burden on the community, you mean that Medicare generally pays for all of this.

Absolutely — Medicare or Medicaid. It might be that money can be used to a much better advantage in the care of citizens where the care given is going to have an effect on the outcome of that disease or illness that the patient has, or preventive medicine measures, whereas, the care that we give to these people — loving care, expensive care — is not going to have any effect, except maintaining biological life.

What guidance do you give your own patients about all of this?

I always insisted that they understand what advance directives were, to make sure that they expressed their own preference about what kind of treatment they wanted if they had a stroke and were unconscious, if they developed the persistent vegetative state, so that there would be no argument by the family. They would have a clear-cut understanding of what was to be done. People, for some reason, don’t want to take thought about that because we all don’t want to talk about our mortality. Young people should have advance directives, too; but you can’t get a 30-year-old to be concerned about “When I die” or “In the dying process, I don’t want to be treated this way. I want to be treated that way.” They just don’t want to talk about it. In the absence of advance directives, then I think a family should get in contact with a medical ethics center, a bioethics center in a hospital or university, an institution, and ask, “Can we discuss all of this in an open way and educate ourselves in regard to this?”