In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Lindisfarne Gospels

The oldest surviving English version of the New Testament Gospels withstood Viking raids and the Dark Ages to be exhibited this summer at Durham Cathedral.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: The large cathedral towers over the small English city of Durham, but Durham Cathedral’s historical imprint is far wider. The foundation of Christianity on the British Isles was profoundly shaped by events, people, and relics connected to this eleven-hundred-year-old structure—including one relic that’s come home to visit from safekeeping in the British Library in London: a book that is thirteen hundred years old.

PROFESSOR RICHARD GAMESON (History Department, Durham University): This is a book that has been dragged around the north of England on a cart, fleeing from the Vikings, and the fact that it is still in near perfect condition shows how highly valued it was over the centuries, that people did look after it as well as they could.

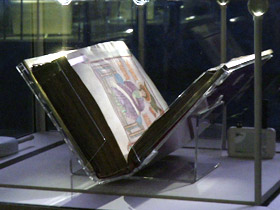

DE SAM LAZARO: And to keep protecting it, Professor Richard Gameson says visitors to the exhibit get to see just one open page of the Lindisfarne Gospels—the illumination of St. John that precedes his gospel. The space is kept cool and gently lit.

GAMESON: “The Lindisfarne Gospels is a remarkable book...”

DE SAM LAZARO: Scholars like Gameson work off facsimiles. This one is a $16,000 exact replica of what he calls a technological and artistic masterpiece and a religious landmark: the first translation of the four gospels into English—an Old English that it takes a scholar to interpret.

GAMESON: "Here begins": "On gynneth, on gynneth." It sounds a bit like "begin." "Evangelium godspell"—close to our "gospel."

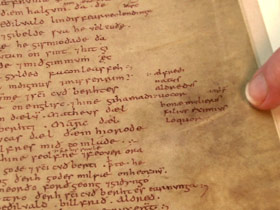

DE SAM LAZARO: The book was first hand-written in Latin around the year 700 from texts brought over from Rome. Three centuries later it was translated word-by-word in English between the lines of the original text by a monk named Aldred. He took special care to clarify critical passages, like the one describing the relationship of Mary and Joseph.

GAMESON: He added the Old English word “bewedded”—“wedded,” we’ve still got the same modern word. However, “wedded” had sexual implications, and of course that would conflict with the doctrine of the virgin birth, and so he then adds various alternatives. He was still not satisfied, and so he added in a note saying that Mary was “entrusted” to Joseph, and he adds “in no wise to have as a wife, but for him to look after her.”

DE SAM LAZARO: Almost as important to Gameson is a side-note written by translator Aldred. It tells of the book’s creation on the remote island of Lindisfarne, just off England’s East coast.

GAMESON: There is a poem hidden within this that goes back to nearer the time the book was made and provides us with the key facts that Eadfrith the bishop made the book, and now we’re told the book is for God, for Saint Cuthbert, and all the saints on Holy Island.

DE SAM LAZARO: On Holy Island or Lindisfarne the spirits of Cuthbert and those long-ago saints can still loom large. Mark Douglas is with English Heritage, a public agency that maintains historic sites and ruins including those at Lindisfarne Island.

MARK DOUGLAS (Properties Curator, English Heritage): The island itself has a certain draw. There’s something special about this island. You find a lot of people actually coming for the spiritual benefits. You get this sort of a tingling of the spirituality of the place.

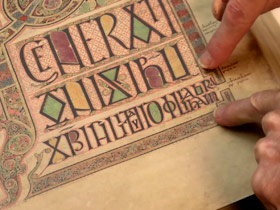

DE SAM LAZARO: It was here in the year 635 that Irish monks set up the priory, establishing Christianity in a largely pagan land and the cult of Cuthbert, a revered early prior. The quiet monastic life ended when Holy Island was discovered by the Vikings, notorious invaders from Scandinavia. By the late ninth century, the monks decided they had had enough of the ever-present threat of Viking raids. They decided to abandon this windswept island of Lindisfarne. They took off for the mainland and took with them two of their most prized possessions: the body of Saint Cuthbert and the gospels. After a years-long trek across the north of England, Cuthbert was reburied in Durham Cathedral, where the monastery was reestablished. His tomb still attracts thousands of visitors. As for the gospels, the book wound up in private hands after King Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in the sixteenth century, and it was later donated to the British Library. Today, Gameson says it offers a chance to rethink a period often dismissed as the Dark Ages: this elegant calligraphy under daunting conditions, parchment from the skins of 149 calves, colored inks made from diverse animal and vegetable sources.

Also, amid the vivid display of his talent, the scribe Bishop Eadfrith was human and made mistakes.

GAMESON: Beautifully set out—Liber generationis, but we can see, as he gets to the last line, slight desperation. He has to fit letters in between other words, and here he even has to bend the frame in order to fit all the words in.

DE SAM LAZARO: In Durham, the exhibit has far exceeded the 80,000 visitors organizers expected.

EXHIBITION VISITOR: I think they're an important piece of world history, because they are something special from the so-called Dark Ages and a copy of what shaped the Western world, Christianity.

EXHIBITION VISITOR: I think it's very, very impressive.

EXHIBITION VISITOR: It’s really nice for the gospels to come back here where they belong, and we think they should stay here.

DE SAM LAZARO: Alas, it’s in Durham just through September. After that it would take a trip to London’s British Library to catch a glimpse. For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Durham, England.

The oldest surviving English version of the New Testament Gospels withstood Viking raids and the Dark Ages to be exhibited this summer at Durham Cathedral.