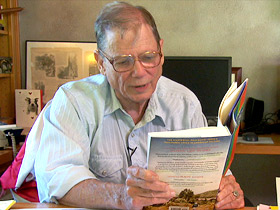

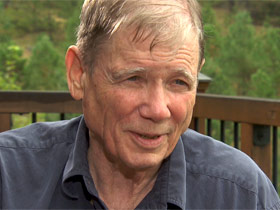

BOB FAW, correspondent: James Lee Burke, now 76, not only pounds a speed bag nearly an hour every day, he also still writes feverishly every day, churning out novels which have sold more than 10 million copies. Burke’s crime stories are modern morality plays about a world which is, in his words, “intransigent and corrupt, a place where moth and rust destroy and thieves break in and steal.”

JAMES LEE BURKE: I write about the world I’ve known, put it that way, and I try to write about it in accurate fashion.

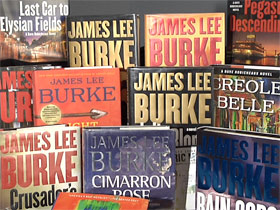

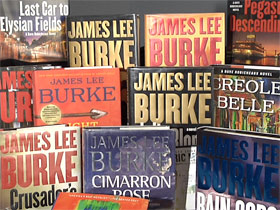

FAW: Burke’s been called “America’s best novelist...the heavyweight champ of nostalgic noir.” But success didn’t come easy: one of his early books was passed around to publishers for nine years.

BURKE: It was rejected by 111 editors, and it is a record in New York. This is the most rejected book in the history of publishing. Everyone says that.

FAW: Once published, it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Until then Burke had to take jobs as a surveyor, reporter, teacher, even a social worker on Skid Row. But he never gave up writing.

BURKE: It’s a vanity. It’s a conceit. Every artist has this notion that he sees the truth about the world in an exquisite, perfect fashion, and he’s compelled to tell others of this vision. He will have no peace until he does so. That’s the compulsion.

FAW: After all that time in the literary wilderness, James Lee Burke struck pay dirt, creating Louisiana detective Dave Robicheaux, who like Burke is a recovering alcoholic who is portrayed here by Alec Baldwin:

From “Heaven’s Prisoners”: “I want a drink all the time. All those colored bottles.”

FAW: The subject now of two motion pictures and 20 novels, Dave Robicheaux, tormented by alcoholism and depression, is a two-fisted St. Augustine-quoting lawman who navigates a demi-monde rife with perversion and bloodshed. Damaged but following a unerring moral compass, Robicheaux is Burke’s modern-day knight-errant.

BURKE: Actually, his character is based one, on the Everyman character in the medieval morality and religious dramas. But also primarily I see his antecedent as the Good Knight in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It’s a great character, the Good Knight, chivalric figure who is always the peacemaker in the story, the pilgrimage.

FAW: That pilgrimage toward redemption, says Burke, is what defines good literature.

BURKE: As far as redemption is concerned, I’m speaking as an artist. I believe the central theme in all Occidental literature is about the search for salvation. It is the basic theme of Western literature, and that’s what we all end up painting, acting out in dramas, or writing about.

BURKE talking to horses: “Missy gets the last one because you were a slowpoke. All right, come here.”

FAW: Robicheaux has brought Burke fame and fortune: two horses on 120 acres nestled in a towering, tree-lined valley near Missoula, Montana where he lives with Pearl, his wife of 52 years, and an impressive firearms collection he so lovingly maintains.

BURKE: Boy, these are a beautiful pair of guns. Pearl gave me these for Christmas.

FAW: And still he writes one thousand words on a good day.

BURKE: It's an incremental discovery. That's what I believe. The right line is there. You got to wait, and you got to hear it, got to hear it. It is all in the unconscious. You just have to listen to it, listen for it. It’s there.

FAW: Patiently copying onto a computer words he’s earlier scribbled into one of his many notebooks, there at his bedside when he needs to write something down in the middle of the night.

BURKE: There is a piece of dialogue here that I know. I don’t know where it goes, but it goes somewhere in the novel.

FAW: In his two latest books, Burke draws upon both his Roman Catholic upbringing and education in classical literature. His voice, says the New York Times, has grown “more messianic...more biblical.

BURKE (reading from the Bible): This is from Isaiah 43:20: “The wild beasts will honor me, the jackals and the ostriches.”

FAW: And it’s not just using an inscription from Isaiah, or language suffused with religious imagery.

BURKE: The stories I’ve written are the Passion Play. I mean, they clearly come out of the New Testament. The imagery, the icons all have to do with Golgotha. That’s what they’re all about.

FAW: Page-turners and major motion pictures, yes. But what Burke is really doing is grappling with some unanswerable mysteries, such as are there people who “love evil for its own sake”?

BURKE (reading from “Light of the World”): “Or could a black wind blow the weather vane in the wrong direction for any of us and reshape our lives and turn us into people we no longer recognize...”

FAW: You talk about the darkness that can live in the human breast. You talk about men “who have no parameters.”

BURKE: Yeah, there’s no explanation. It’s just an aberration. It’s something that allows them to step over a line, or as Dave Robicheaux says, “They murder all light in their souls.” Dave says they try to erase the thumbprint of God from their souls. But nobody knows why.

FAW: In his writing he might have wrestled with some of those eternal mysteries, but James Lee Burke does not pretend to have found the answers.

BURKE: When you get down into the top of the ninth, when you’re standing on third base, you realize the great mysteries were going to remain the great mysteries. If wisdom comes with age, it has bypassed me like a freight train.

FAW: In the end, Dave Robicheaux, though he rarely turns the other cheek, does find a kind of peace and a perspective about what is important in life.

BURKE (reading from “Light of the World”): “At the bottom of the ninth, you count up the people you love, both friends and family, and you add their names to the fine places you’ve been and the good things you’ve done, and you have it.”

FAW: That’s it?

BURKE: That’s it, brother.

FAW: That’s wisdom?

BURKE: I don’t know if it’s wisdom or not. It’s the way it is.

FAW: A no-nonsense approach much like advice Burke was given long ago as a Catholic schoolboy.

BURKE: A Franciscan told me once, don’t keep track of the score, the score will take care of itself. You never measure yourself in terms of days or weeks or months. In theology it’s called the fundamental option. You make your choice, you make your troth, you never go back on that silent contract you make, and you’ll be pleasantly surprised at the arithmetic on the scoreboard in the bottom of the ninth, and that’s how it works.

FAW: James Lee Burke, at 76: confronting the past, embracing the present, pounding away hard as ever.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Bob Faw in Lolo, Montana.