BOB ABERNETHY: Now, a special report on the plight of churches in America's Great Plains. As corporate farming displaces more and more family farms, ranchers and farmers move away, local businesses shut down, schools consolidate, and, finally, congregations become so small they have to close their churches. Judy Valente reports from North and South Dakota on what it means when long-familiar churches disappear.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #1: It's a hard life. And ranching is not easy. The weather, nature take a lot of a toll.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #1: No. When we first started, there was a lot of young farmers out here. But ...

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #2: ... the last census showed that we were the only state in the union who had lost population in several tens of thousands.

JUDY VALENTE: The high plains of the western Dakotas. They've been called as quiet as a monastery, except for the wind. Homesteaders came to the Dakota Territory in the mid-19th century, Catholics and Lutherans from Germany, Hungary, and Scandinavia. They got 160 acres of sometimes rocky, arid land. If they worked it for five years, the land was theirs.

Mr. STUART SCHMIDT (Rancher): It's a very traditional ranch ran in a very traditional manner, very similar to the way they were ran 100 years ago.

VALENTE: Stuart Schmidt raises 400 head of cattle on 10,000 acres near Lemmon, South Dakota. Better cows than plows, he says. In a time of big corporate farms, small operations can no longer survive. Despite its vast expanses of open space, North Dakota is now considered an urban state. More than half its population lives in cities and towns, not on farms.

Those who can't compete sell or abandon their farms and move away. Older folks move to the cities for better health care. They leave behind not only abandoned farms but abandoned churches and unique faith communities that are fast disappearing from American life.

Mr. SHANE SICKLER (Rancher): Well, I figure the church is the most important thing out here, more so than a barn or a house. It was the first thing that the settlers -- when they moved here, they moved here on faith and they built that church on their faith, and that was their backbone that kept them here.

VALENTE: Out here, the towns are small and far apart, which is why people drive a long way to attend Sunday services with their neighbors. This is Hope Presbyterian Church in South Dakota. It is in the middle of nowhere.

Mr. RICK DARNELL (Pastor): If you asked me to go through and pick out who's Presbyterian and who's Lutheran or Catholic or whatever in the cong -- I couldn't tell you. It's just whoever comes, comes, and that's who we serve.

I believe in God, the Father Almighty, maker of ...

VALENTE: Rick Darnell is the part-time pastor, but he isn't an ordained minister. He can't perform weddings or baptisms. The former pastor left last fall. Darnell took the job because no one else volunteered for it.

Mr. DARNELL: These are people that -- they like what they do. They like where they are and it shows. Here you get much more of a sense of sitting around a dinner table and telling stories. There's more interaction, you know, with the congregation.

VALENTE: On this Mother's Day, flowers for the women in the congregation. And for the young people graduating, best wishes for the future, a future that will most likely take them somewhere else.

Mr. DARNELL: Do we have joys or concerns this morning to share?

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #2: We need to be thankful for all the good moisture we got this last week.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #3: Oh, yes.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #4: Bonnie is just not doing well. She's -- you know, it's hard to speak yet. She's lost a lot of weight. She just needs some prayers.

VALENTE: After the service, coffee and cake. And the ranchers talk about keeping their congregation intact.

Mr. SCHMIDT: It would be a big loss. We would lose our fellowship.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #5: People recognize if they want a community, they're going to have to make it. And they can't let petty differences ...

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #6: Right.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #5: ... and feuds interfere.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #6: The young people that have grown up here and the community couldn't support them, like Brad and Clint and all these kids, they all want to come back.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #5: Yeah.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #6: You know, there's something about the community that just says ...

Mr. SCHMIDT: Magnetizes them ...

UNIDENTIFIED MAN #6: Yeah.

Mr. SCHMIDT: And the wives all ...

VALENTE: But if there isn't a way to make a living, they don't come back. And eventually congregations die. That's what happened at St. Philip's Catholic Church across the state line in North Dakota. It was down to 18 families when the archdiocese decided to shut it down.

Mr. S. SICKLER: You remember the church. It's where you met your cousins the first time. It's where you met your friends and -- or you developed friendships.

VALENTE: Glen Sickler, a cousin, and his wife Joan live a couple of miles away. Each of their four daughters was married at St. Philip's. The last person to be baptized there was one of their grandchildren. The church was their social life.

Mr. GLEN SICKLER (Rancher): I've got to say there's some neighbors I have never seen since the church closed. And that's been just about two years now. I've never seen them really since.

Mrs. JOAN SICKLER: It's not there anymore. The closeness is gone.

VALENTE: When a church closes, the people have to decide what to do with the building. Some are used for special occasions or converted to other uses. Many are simply abandoned and others, like this one, are burned. Some parishioners considered burning St. Philip's.

Mrs. SICKLER: To see the flames would have just been awful, I think.

Mr. S. SICKLER: I don't want to see a church burn. I don't want to see a church burn any more than you would want to see your whole family house burn once it was done living in it.

VALENTE: Finally, the parishioners decided to have the church torn down. A carpenter is taking it apart piece by piece.

Mr. CHRIS DAHNER (Carpenter): Some days, it's pretty darn sad because, you know, I -- you look at this church. This was built with hand tools. This wasn't built with power tools. To let it tarnish away and weather away and eventually when one of the big winds that we get here come and push it over, I think that would even make me feel sadder.

Mrs. SICKLER: Oh, it was a very pretty country church. It had a lot of wood in it.

VALENTE: Tom Richter is a young priest who spends a lot of time on the highway. He teaches school and is the pastor of three different churches in three different towns. It was his job to close St. Philip's down.

Father TOM RICHTER: This whole rural crisis that -- is not just a financial thing. But it's about deaths in their lives to important things in their life, and one being the parish.

Dr. JACK SEVILLE (United Church of Christ): The main threat to the community of losing churches is the pastoral care. Who cares for people at times of death, at times when people need counseling?

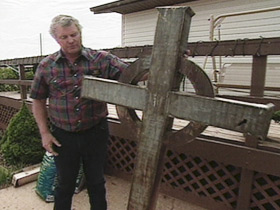

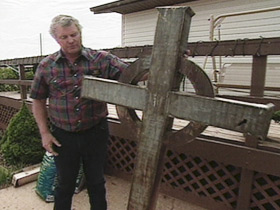

VALENTE: Chris Dahner plans to make furniture from whatever wood he can salvage from the church. When demolition began, Glen Sickler took the cross from the steeple.

Mr. G. SICKLER: I'd like to take it and put it up into the cemetery, mount it up there so it's -- make a memorial from the church.

You can see that it's all handcrafted and somebody took a lot of time to make it. It looks like even, somebody maybe even shot it with a gun at one time.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #3: When he took it down...

Mr. G. SICKLER: That's the way it came off the church and that's the way I want to put it back up into the cemetery, so ...

VALENTE: Not so many years ago, there were 2,000 churches in North Dakota. Four hundred have now closed. About 15 shut down every year. An organization called Preservation North Dakota is trying to save them, but has few resources and gets no public money.

Ms. BARBARA LANG (Preservation North Dakota): From the state and federal government, no, we really don't. Again, it's the issue of the religious properties and the separation of church and state.

VALENTE: And for the churches that remain, there aren't enough clergy to go around.

Fr. RICHTER: If you don't learn how to say no, you will die. And the work will kill you. Before I became a priest, I thought it would be a lonely life, being celibate and all that. And now, quite honestly, I try to hide as much as I can. I long for more time alone. I long for more solitude.

Dr. SEVILLE: I've trained over the last 20 years over 100 laity in both Dakotas to preach and teach in our churches, in the United Church of Christ, and other denominations are doing the same. North Dakota might be the first state in the United States where denominations will come together and agree that our goal will be to provide a clergyperson for the town, regardless of how many churches are there, regardless of the differing faiths that are there.

VALENTE: Congregations like Hope Presbyterian will hang on as long as they can, but the exodus of farmers, present and future, seems irreversible. Some of the historic church buildings may be saved, even though they've been all but abandoned. Others will fall slowly into ruin, and still others will be torn down, with worshippers salvaging what they can, like the cross of St. Philip's to be erected in the cemetery overlooking what will soon be an empty field. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Judy Valente in Hershville, North Dakota.