LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: There is always the one big question after mass killings at places like the Aurora theater, Sandy Hook Elementary, Virginia Tech: could this violence have been predicted, or even prevented?

PROFESSOR ADRIAN RAINE (University of Pennsylvania, Author of The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime): I believe firmly there are things we can do to not just treat violence but also prevent it.

SEVERSON: Adrian Raine is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a pioneer in the field of neurocriminology. He has written a controversial book called The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime.

PROF. RAINE: It’s beyond a reasonable doubt now that there is this brain basis to crime. This research at one point was suppressed and ignored by social scientists for lots of ethical reasons basically, but now we’re out in the open with this information and we can’t go on ignoring it anymore.

PAUL WOLPE (Emory Center for Ethics): I’ve enormous respect for Adrian Raine and I think he’s an excellent scientist. I cannot think of anything more dangerous than his policy recommendations.

SEVERSON: Paul Wolpe directs the Center for Ethics at Emory University and is the co-editor of the scholarly American Journal of Bioethics. He, like other scientists, believes neurocriminology is an important new but undeveloped science with serious moral implications.

WOLPE: We find a new scientific technology, we get all excited about it, we think it will answer problems for us, we start to implement it and we hurt people. I want us to have the ethical wisdom right now to not rush to judgment about neuroscience.

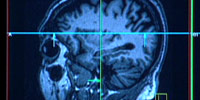

SEVERSON: Raine has been studying the connection between the brain and violence in children and adults for 35 years. He says his research shows that the brains of psychopaths have a deficiency in the part that governs feelings of remorse and empathy for the victims.

RAINE: What we see in psychopaths who are very fearless individuals and who create a lot of harm to society is that they have a reduction in a part of the brain called the amygdala, the part of the brain that’s very much involved in moral decision making, in empathy, in conscience, feeling remorse, feeling guilt which is one of the reasons they do such terrible things.

Researcher: In this task, you'll be shown a series of scenarios. You should immediately respond to the question by pressing the "yes" or "no" button.

RAINE: You take normal people, and if you give them a moral dilemma like would you kill one person to save lives? That’s a difficult decision for many of us. But when we do the same thing with psychopaths, their amygdala is functioning much less. Then how moral is it of us to punish psychopaths as harshly as we do, assuming that they never asked to be born with an amygdala that was broken.

WOLPE: Two people often can have a lesion, or some brain abnormality in exactly the same place and it manifests itself in completely different ways.

SEVERSON: Raine agrees that two people can have the same defect and one might resort to violent crime, the other to violent sports. But, he says, there are now more reliable bio-markers that should not be ignored.

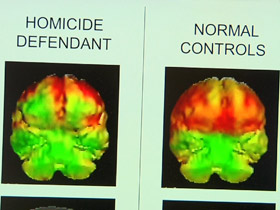

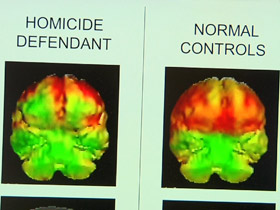

RAINE: You look at the murderer here and you can see a distinct lack of activity in that prefrontal cortex.

SEVERSON: So this person is not sensing that raping this person, killing this person is wrong, that it’s morally reprehensible?

RAINE: That’s correct.

SEVERSON: Raine testified as an expert witness in the trial of Donta Page who brutally raped and murdered a young woman. His testimony helped get the man’s sentence reduced from the death penalty to life in prison.

WOLPE: So defense attorneys are taking scans and saying “Can I find anything abnormal in this scan?" And if they do, they can hold that up to in front of a jury and say, “Look at this. The neuroscience expert has told us that this looks odd, or is different than average, my client couldn’t help themselves.”

RAINE: Cut them a break. You know you can’t hold them fully responsible as we do other people. We’re not all equal and for some individuals the dice are loaded early in life conspiring to push them into a life of crime.

SEVERSON: He sees a real benefit to society when brain imaging can predict which kids are most likely to end up in trouble and then work to develop treatment programs to prevent it. He has twin boys of his own.

RAINE: As a parent I want to know, and I think every parent should know, is their child at risk for becoming a violent criminal offender? We’ll never be able to predict with perfect accuracy which children are going to become violent offenders of the future, but we have information, some information now which does tell us that some kids, the odds are raised that they will become a violent criminal offender.

WOLPE: To try to suggest that we could learn something about their brains right now that would lead us to engage in any kind of different behavior towards them is not only extremely problematic and premature, it is dangerous, because we have seen over and over again the power of stigmatizing children.

SEVERSON: Where Raine and Wolpe agree is that brain imaging could be very useful in predicting which inmates will commit new crimes when they’re released. And there are few places that need that kind of risk assessment more than the Los Angeles County jail system. Terri McDonald is the Assistant Sheriff of L.A. County and until recently the head of Risk Assessment for the state of California.

TERRI MCDONALD (Assistant Sheriff, L.A. County): The State of California uses the California Static Risk Assessment tool.

SEVERSON: What is that?

MCDONALD: That tool is an actuarial tool that takes information from an offender's rap sheet, their arrest history and it downloads that information into a database system. From that, it pops out a score for the offender that predicts their risk of reconviction, re-arrest.

SEVERSON: California has a much more sophisticated risk assessment program than the L.A. jail system which has granted early release to over 26,000 inmates so far this year because of extreme over-crowding. Usually those inmates who qualify, for instance those not in for violent crimes, get released after serving only 40% of their sentence, some after serving only 10%.

MCDONALD: If a system has to release early, it should be based on risk. You know, we do it based on percentage of time served and it’s because we’re so large. We have 500 inmates coming in and out of the door every day and to do risk assessments, a manual risk assessment on 500 inmates takes a lot of people do to that. It’d be very expensive for every inmate in the L.A. county system to have that assessment done, so it’s not done for everybody.

SEVERSON: There is research underway, but as of yet, prisons are not using brain scans to predict recidivism.

RAINE: We’ll never be able to perfectly predict future violence, but look, let’s face it, will it become public policy? In a way, everyday we make decisions on which prisoners we release early. Do we lock them up or do we give them community service? And right now brain imaging research is showing that brain imaging data is giving added value in these predictions.

MCDONALD: We in L.A. County and in every other county in California has to get better at how we do risk assessments. It’ll be fascinating to learn as time goes on how physiological testing could help as one component of an overall review of an offender. You don’t ever want to rely on any one system.

WOLPE: We have to be very, very careful how we use this information, which again is not to say that we might not be able to use this information well, but to use it poorly is, so, so dangerous.

SEVERSON: Adrian Raine is the perfect example of how far neuroscience has come and how far it has yet to go before it is a reliable predictor. He says he has some of the bio-markers of a serial killer and yet he grew up to be a neurocriminologist. For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Philadelphia.