BOB ABERNETHY: Here's a question: when a person has a religious experience, what happens within the brain? What kind of changes take place?

Science has been looking into this. In one experiment, for example, brain scans examine the parts of the brain that are activated during prayer. In another, mystical and religious experiences are simulated by using bursts of electrical impulses. As you might expect, these experiments have created no small amount of controversy. Lucky Severson reports:

Dr. MICHAEL PERSINGER: I think one of the most exciting challenges in science is to find the basis, the empirical basis, of why people experience the "God phenomenon." Not belief in God -- that is a different process. But the experience of the "God phenomenon." That of course is tied to the brain itself.

SEVERSON: Dr. Persinger is a neuroscientist who has been conducting experiments with a helmet that pulses tiny bursts of electrical activity into the brain. Persinger says the pulses can simulate mystical or spiritual experiences.

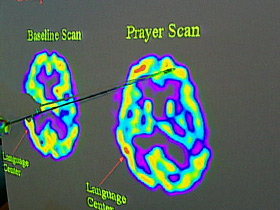

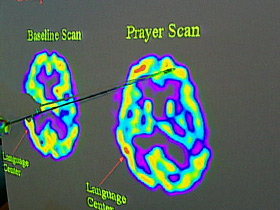

And at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Andrew Newberg can show, through a brain scan, the parts of the brain that are activated during meditation, and also during prayer.

(to Dr. Newberg): What's the significance of all this? What does it mean?

Dr. ANDREW NEWBERG: Well, what it means is that when people actually do these kinds of spiritual practices, when people do prayer or meditation, that there are real changes that are going on in their brain.

SEVERSON: The concern of some religious believers is that this new research might imply that God is a concept created in our brains rather than a transcendent being who exists quite independent of us.

Ms. GRACIA THOMPSON: I feel it would be against God to try to alter or change anyone's belief of Him.

Mr. RAMIRO GARCIA: I cannot conceive of living without the presence of someone greater than ourselves to lean on.

SEVERSON: Dr. Persinger says his experiments can actually induce the sense among his subjects that there is a presence in the room with them.

Dr. PERSINGER: The types of experiences in our laboratory when magnetic fields are applied to the brain are considered spiritual because the person feels at one with the universe. Very often it is very personal. There may be a sensation of quiescence, a kind of eternal peace, but they know that somehow their sense of self has been changed forever.

Professor JOHN HAUGHT: This is something that is not entirely new. A lot of people have testified, for example, that under the influence of LSD or cocaine or other stimuli to the chemistry of the brain, that certain ideas happen that didn't happen before.

SEVERSON: John Haught is a professor, not of science but of religion, at Georgetown University. He argues that religion encompasses much more than biology -- that it means charity and faith and doing good works.

Prof. HAUGHT: I would say that in this recent flurry of news about the brain and religion, what is often left out is that religion means much more than a state of mind or [an] ecstatic or mystical mood. It's a commitment over a lifetime to what a person considers to be good.

SEVERSON: Among the scientists in the field, Dr. Persinger is controversial because he has stated in the past his view that God is a creation of the brain.

Dr. PERSINGER: There are Christians and individuals of other faiths who have come to me, very often hostile at first, pointing out that I am threatening their belief, accusing me of being an atheist and often worse terms. I am not trying to remove God as a phenomenon. I am trying to understand the areas of the brain and the magnetic patterns -- the electromagnetic patterns -- within the brain that produce the experience.

SEVERSON: Dr. Newberg argues his experiments with meditators and those who pray doesn't disprove God.

Dr. NEWBERG: When I take a brain image of a nun who has the experience of being in the presence of God, what I can tell you is that this is what is going on in their brain when they have that experience. What I can't tell you, just based on imaging studies alone, is whether or not they've actually been able to do that, they've actually been in the presence of God. But I think it raises some very interesting issues and questions for us, as scientists and also as philosophers, to be able to explore where the true reality lies.

SEVERSON: Dr. Michael Baimes is one of Newberg's subjects -- an expert on meditation and stress management.

Dr. MICHAEL BAIMES: It's pretty darn interesting to see that when people do this ancient meditation practice, a predictable change in brain function happens.

SEVERSON: Here's how it works. After the subject has meditated, Dr. Newberg injects them with radioactive dye and he takes pictures of their brain. As they get deeper into their meditative state, the colors depicting brain activity change.

Dr. NEWBERG: But when the person went into the meditation, what we see is a dramatic decrease over here in this particular orientation area, and this is that particular part that helps us differentiate the self from objects in the world.

SEVERSON: When we meditate and pray, for instance, the part of the brain that helps us orient ourselves and create a sense of self shows less activity, less red -- the brain quiets down.

Dr. NEWBERG: What they are perceiving is a sense of being at one with something else, in this case, the idea of being within the presence of God, or finding some way of becoming joined or in union with a sense of God.

SEVERSON: Newberg believes the brain is engineered to allow spiritual experiences. And Professor Persinger in Canada believes that the brain over generations has evolved to what it is today to allow spiritual experiences.

Dr. PERSINGER: People are afraid to die. The sense of diminishing, that tremendous terror of losing a sense of self is incapacitating. So I think somewhere in the development of the brain there was a kind of cognitive process that allows people to have minimal anxiety if they just felt that the self, part of brain activity, was tied to a concept that was infinite and lasted forever. If something is infinite and lasts forever, there is no anxiety. And I think that spirituality that comes out of that process has allowed the human being as a group -- as a species -- to survive.

SEVERSON: So is it possible that one day science will be able to prove or disprove God with a certainty? A goal of science perhaps, but for many of the faithful, a waste of time.

Prof. HAUGHT: The conflict is not between science and religion or science and theology, but it's between two belief systems: the belief system that matter is all there is and the belief system that there is something in addition to matter.

Dr. NEWBERG: If there is a God, it certainly makes sense that the brain is set up this way, because it would be silly for us to have some fundamental disconnect with the God that created the brain.

SEVERSON: Like other neuroscientists delving into religion, Professor Persinger has taken some heat for his work. He may be more careful now about what he says, but what he says is that science is not threatening religion.

Dr. PERSINGER: The fact that we can now understand the brain basis to faith simply tells us that we can understand it more effectively. It doesn't make it go away any more than when you look at the brain and you are seeing a sunset, and it is beautiful. It doesn't take the beauty away, it just allows you to understand more of it.

SEVERSON: So the science continues, and the debate. And the question: "Will the science challenge the faith of the believers or will it simply add to it?"