In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

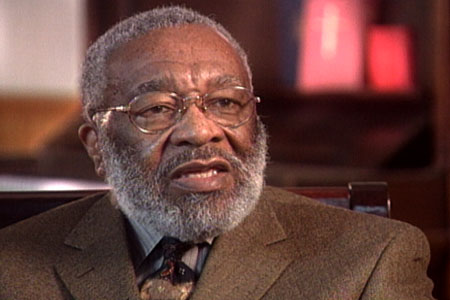

Dr. Vincent Harding and Dr. Rachel Harding Extended Interviews

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview about art, social change, and Martin Luther King with Vincent Harding and his daughter, Rachel Harding.

On the interrelation of the arts, spirituality, and social change:

Dr. Vincent Harding: Often when I’m thinking about these things, I’m thinking about the music that came out of the freedom movement. I’m remembering literally what people looked like when they were singing these freedom songs. I have constant memories that people, in a sense, were singing their freedom. They were indicating by the songs themselves that they were determined to move towards freedom. The creativity of song was a part of the creativity that they were exhibiting in the Southern freedom movement particularly, in creating a new society.

I see creativity not simply in creating particular works of art, or creativity in doing a particular piece of music; creativity was expressing itself by people saying, “We can build a better world. This is our creative contribution to this society and to this world. And we’re going to let you know how we feel about this by singing the songs that we are creating or re-creating.”

One of the things that comes to my mind, for instance, would be Mrs. Fanny Lou Hamer taking the songs of the Christian religious tradition, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” to “Let my people go.” She takes an old African-American Christmas spiritual and brings the Hebrew story of “Let my people go” into that and brings the struggle of black people in America in our own time into that. I was fascinated one day back in what seems like a long-ago time now, when the Berlin Wall was being dismantled, to hear people on top of that wall, taking those bricks down and singing in German that same song. So for me, creativity is in the acts of creating a new society, and the songs that came out of the acts — all of that is part of the creativity.

On art and Martin Luther King:

Martin King was an artist in a whole variety of ways. One of the ways is his use of the language of the people — taking the language of the people, returning it to them as they had given it to him, and creating in many cases a higher form that they could know was actually theirs, and therefore they could feel very right about participating in the creative action with him, the action of transformation. It was in that language, in that sensing that change was possible, in that envisioning of new possibilities, in that dreaming that we saw the artist in him coming through.

On Dr. King and the freedom songs:

For King, the songs were as much a part of his life as breathing. It was nothing that had to be added on or brought in; he didn’t have to say, “Oh, we ought to have some songs in this mass meeting.” There was no way you could meet without singing. There was no way in which you could organize without singing. Singing became central to the whole experience. I remember back in the days when the Nation of Islam was in an earlier form, when they were very determined to be as unlike Christian churches as possible and decided that they weren’t going to sing. I was talking to a friend of mine from Vietnam who had been involved in the struggle against French colonialism, and I said to him, “John, have you ever known a freedom movement where there was no singing?” And he said, “I can’t think of one.” You simply have to have song in order to work for freedom. That was a part of Martin; he simply had to have that. In a way, you could say that his preaching was a kind of singing; that was his artistry. But all of that was just almost not necessary to be thought out in categories. All of that flowed together as a part of the art of creation.

I have long been very moved by one of the songs that was used in the movement, “This Little Light of Mine,” which a lot of people knew from Sunday school and other settings, but which took on a whole meaning. I’m moved by what happened in Selma when they used that song in the midst of tremendous dangers and misuse and abuse by the authorities there. The young people sang, “I’m gonna let it shine. This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine.” Then they said, “Tell Governor Wallace…” But what they said was not, “Tell Governor Wallace he’s a white honky and he’s no good”; they simply used the song to say, “Tell Governor Wallace I’m gonna let it shine. … Tell Chief Clark I’m gonna let it shine.” They didn’t need to attack those people; what they needed to do was powerfully, through the song, affirm that they had a spirit in them that they were going to share with the world, and no one in the world was going to stop them from doing it. That has always been a memory for me — the way they refused to enter into the destructive spirit of their oppressors but instead took their powerful strength, which was always represented by Martin’s action and preaching, and in their own particular way said, “We too are the carriers of light, and we want the governor and the police chief and everybody else to know that we’re going to keep carrying it, too.”

On art and religion:

Dr. Rachel Harding: The impulse to art, the impulse to creativity is very similar to the impulse to spirituality and to imagining and creating a more humane society. I think at root, the more exalted artists in our global societies as well as folk artists are looking for ways to express the deepest parts of their own humanity, and the deepest connections that they’re able to manifest, whether in song or in visual art or in dance, with something higher — a kind of collective meaning of who it is they are and how it is they’re connected to something beyond themselves. And religion, I think, at its base is that as well, an attempt to try to find something outside of our own individual identity that connects us to something larger, that stretches out beyond where we are and that is a part of what we come from… I think of artists in the African-American tradition such as John Biggers, Jacob Lawrence, and Elizabeth Catlett who represent the constant focus on the deep humanity, the deep dignity of their people who have struggled and been through so much trauma and hardship. But at the same time [they use that] as a foundation to stretch out and stretch up and connect with the humanity that all people share. Religion at its best does that too; it comes out of a particular and a specific experience, but it moves us toward a connection with others — the spirit.

On telling the story of the freedom movement:

Dr. Vincent Harding: One of the things we are most concerned about is that a younger generation comes into as vital and creative contact with this story as possible. It is absolutely necessary to find as many ways as possible that will tie into the experience of younger people, tie into the contemporary experience, whether it be television, video, murals, songs in a new genre. We’ve got to find ways; just as that generation took the songs from the past and brought them into new relevance for that struggle, so now we have to go back there, take those, bring them into this time. Every people, every generation, every society has to keep watering the seeds before them in order that the new plants can be of value to those who are living in the present time. Every mode and means of creativity that we can find to tell this story is absolutely necessary, because the story must not only be a story; it must be a reason for living for another generation.

It is powerfully motivational to realize how many people were not alive 35 years ago, 40 years ago, when my wife and I began to be involved in this movement ourselves. There’s a tremendous motivation to say, “We’re going to have to find some way to tell this story.” We feel that because of what we have seen and known and because of a companion like our daughter, we have a great ability to respond. Responsibility means that to us, for one thing. It also means a great privilege. We have lived through one of the great periods of human history and certainly one of the great periods of our country’s development. And therefore there’s a beautiful possibility that we have for sharing what we have known.

Dr. Rachel Harding: What excites me most is as I look around the country, I’m aware of lots of people, particularly in the arts, who are finding different ways of interpreting and passing on the meaning of this story. I’m thinking for example of Cleo Parker Robinson, a local choreographer and dancer here [in Denver], and Ronald Kay Brown, who’s this wonderful African-American choreographer doing tremendous things to link up history and movement and spirituality in the dances that he creates, and a whole generation of word artists, poets, and performance artists who are building on the tradition of the black arts movement, the Chicano arts movement, the women’s coffeehouse poet movements from the ’60s and the ’70s, who are carrying on this tradition of passing on the story.

I am thrilled when I travel to different parts of the country and see the kind of energy and impetus that the movement that my parents and people of their generation were a part of has continued to ignite in folks my age and even younger. It’s very exciting, and you see it across the arts — in dance, in writing, in visual arts, in the music. This has something to do with the fact that human beings are always looking for ways to express our deepest humanity and our deepest connection to others. The movement for African-American rights and the expansion of democracy, as my dad likes to call it, was quintessentially that kind of thing, so there are a lot of people all around the country and other parts of the world who draw inspiration from it.

On poetry:

Dr. Rachel Harding: For me, poetry has been a way to make those spiritual and ancestral connections that become sources of sustenance in my life. Poets I admire and consider my mentors, such as Sonia Sanchez, Lucille Clifton, and Nathaniel Mackie, would describe the meaning of the work in similar terms. It’s a way to connect to something that gives you deep roots. And with the roots, then, you’re able to stretch out and move in directions that perhaps you wouldn’t have had the strength or the inspiration to do otherwise.