FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: For the Bowen family, this was a huge day.

JENNY BOWEN: She got the international baccalaureate diploma, and then she got the bi-literacy medal, as opposed to bilingual. She can read and write—and talk.

DE SAM LAZARO: That 18-year-old Maya Bowen can talk let alone graduate with honors seems both natural and unlikely, given her early childhood in a distant orphanage. Richard and Jenny Bowen adopted her when she was two.

BOWEN: No one had ever talked to her and, you know, language develops when people talk to you. That’s how you learn to speak, so she had no language at all.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Bowens were moved to adopt—first Maya and later Anya—after reports in the late nineties of child neglect on a vast scale in China. This film, shot undercover, called The Dying Rooms, showed orphanages filled with girls abandoned in a country that had begun restricting families to one child in a culture that traditionally favored boy children.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Bowens were moved to adopt—first Maya and later Anya—after reports in the late nineties of child neglect on a vast scale in China. This film, shot undercover, called The Dying Rooms, showed orphanages filled with girls abandoned in a country that had begun restricting families to one child in a culture that traditionally favored boy children.

BOWEN: We thought the thing we could do is save one life. So that’s what we did. We went to China to save a life.

DE SAM LAZARO: But she found it impossible to ignore the conditions Maya would escape, but where millions of others still languished—in the custody of indifferent or untrained workers, invisible in a nation focused on industrializing its way out of third-world poverty.

Sixteen years later, Jenny Bowen heads a group called the Half the Sky Foundation that’s helping transform the way orphans are cared for across China. Her agency—whose name derives from a Chinese proverb that says women hold up half the sky—has trained 12,000 teachers and nannies in 27 provinces across this vast nation. We visited this facility in the northeastern city of Shenyang.

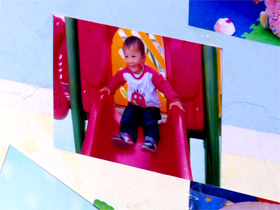

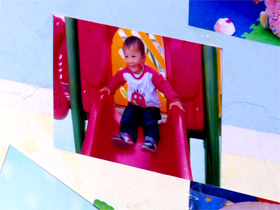

BOWEN: All these children are abandoned. Many of them are abandoned because they have what are called special needs. Before Half the Sky, children were tied to their chairs. They were lying in bed. You could see the tragedy. You walk into a room, and you were just confronted with the tragedy. Here it’s invisible. These children are going on with their lives. They’re being treated like their lives matter. They know it, and they know they’re loved, so they thrive.

DE SAM LAZARO: She says children need a sense of being part of a family, in whatever shape family takes.

DE SAM LAZARO: She says children need a sense of being part of a family, in whatever shape family takes.

BOWEN: It doesn’t mean that they have to be back with their birth families or permanently adopted or anything. They just need to have the love that a family gives naturally to a child, and to me it was like a no brainer.

DE SAM LAZARO: It was not a no-brainer to get her ideas across in an opaque state-run welfare system. What’s more, the publicity about orphanage conditions was deeply insulting to a government highly sensitive about China’s image. Zhang Zhirong works for Half the Sky’s China offices.

ZHANG ZHIRONG: China always want to tell the world she is the best. Everything perfect. We are serving the people, we are helping the people. That’s China politically. At that time it was difficult to let people, especially foreigners, to come in and see some of the problems, to see some of the dark side.

DE SAM LAZARO: Zhang was a key early ally. An English professor and official interpreter well-versed in the culture and politics of the bureaucracy, Zhang was convinced of Bowen’s sincerity.

ZHANG: I really felt she had the heart. She wanted to help. No other intentions.

DE SAM LAZARO: Did it help that she had Chinese daughters as well?

ZHANG: She always says, “I’m half Chinese. My daughters are all Chinese.”

BOWEN: I know that resonated. The international criticism certainly let them know that something had to be done. I was probably the least threatening of the options out there.

DE SAM LAZARO: Bowen began by seeking guidance from child development experts. She raised funds in Hollywood where she’d worked as a screenwriter, and from American couples who’d adopted Chinese daughters. She organized volunteer trips to train caregivers and transform the environment in which orphans spent their days. Children who once sat impassively are now in busy pre-schools. Walls that had generic cartoon images now display the children’s own artwork and pictures.

DE SAM LAZARO: Bowen began by seeking guidance from child development experts. She raised funds in Hollywood where she’d worked as a screenwriter, and from American couples who’d adopted Chinese daughters. She organized volunteer trips to train caregivers and transform the environment in which orphans spent their days. Children who once sat impassively are now in busy pre-schools. Walls that had generic cartoon images now display the children’s own artwork and pictures.

BOWEN: Children in institutions, traditional institutions—they move in packs. They all eat at the same time, they all sleep at the same time, they all pee at the same time, and they don’t separate themselves from each other. So we use a lot of mirrors, things like this, where they can identify themselves, their friends, and it’s a way for them to start knowing who they are, and that’s the beginning of developing intellectual curiosity and opinions.

(Speaking to child): I can tell you already have opinions...

DE SAM LAZARO: Teacher Lin Lin says Half the Sky’s approach, called “responsive care,” is tailored to children’s individual learning interests—a far cry from the previous rote learning.

LIN LIN: Kids were asked to recite a lot of things, old poems and literature, which they did not understand, they weren’t interested in. Now we’re doing things that are interesting to them. Gradually you build a trust with these children, and they begin to consider you as part of their family.

DE SAM LAZARO: That’s a key goal: to make such caregivers part of the child’s understanding of family. But Half the Sky is also building so-called family villages, a more traditional setting. Couples, most with grown children, are given housing and a small stipend to raise their young charges. It’s an easy sell in a country where large families used to be the tradition.

Liu Peng Ying: These are like my own children, like my grandchildren. My husband likes children even more than I do. That’s why we decided to apply for this program.

Liu Peng Ying: These are like my own children, like my grandchildren. My husband likes children even more than I do. That’s why we decided to apply for this program.

DE SAM LAZARO: They’ll live here until adulthood, unless placed in adoptive families. In today’s wealthier, more urban China, Bowen says fewer healthy female babies are abandoned. Anywhere from one to three million children are in state custody. They are more likely to be from impoverished rural areas and more likely to have congenital or medical conditions their families cannot afford to treat. Many are unlikely to be adopted. For them, Half the Sky runs a care center in Beijing. Supported in part by the government and corporate donations, it has medical supervision and nannies for children awaiting or recovering from surgery—or, as in the sad case of four-year-old Pin Pin, chemotherapy.

Bowen (speaking to care giver): Cancer in both eyes?

Care giver: Yes. And eight times chemotherapy.

DE SAM LAZARO: For the weeks or months Pin Pin will spend here, a teacher will help her adjust to the loss of her sight.

Bowen (speaking to child): You need to have a teacher, because you have a lot of things you need to learn. We don’t just worry about your eyes. We have to worry about your brain.

DE SAM LAZARO: Maya Bowen plans to become an elementary teacher. She and Anya, a high school junior, have gone from being thankful to impressed.

MAYA BOWEN: I did a paper at school, a research paper, and we could do it on anything, so I chose my mom, because I thought that would be an easy topic. So then, when I started researching and learning everything she did, I was like, wow, like this goes way farther than I thought. She has like a much bigger influence than I ever thought.

DE SAM LAZARO: Jenny Bowen recently published her own epic called Wish You Happy Forever, the happily-ever-after story of a fifty-something screenwriter turned adoptive mother turned CEO of the seven-million-dollar Half the Sky Foundation.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Bowens were moved to adopt—first Maya and later Anya—after reports in the late nineties of child neglect on a vast scale in China. This film, shot undercover, called The Dying Rooms, showed orphanages filled with girls abandoned in a country that had begun restricting families to one child in a culture that traditionally favored boy children.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Bowens were moved to adopt—first Maya and later Anya—after reports in the late nineties of child neglect on a vast scale in China. This film, shot undercover, called The Dying Rooms, showed orphanages filled with girls abandoned in a country that had begun restricting families to one child in a culture that traditionally favored boy children. DE SAM LAZARO: She says children need a sense of being part of a family, in whatever shape family takes.

DE SAM LAZARO: She says children need a sense of being part of a family, in whatever shape family takes. DE SAM LAZARO: Bowen began by seeking guidance from child development experts. She raised funds in Hollywood where she’d worked as a screenwriter, and from American couples who’d adopted Chinese daughters. She organized volunteer trips to train caregivers and transform the environment in which orphans spent their days. Children who once sat impassively are now in busy pre-schools. Walls that had generic cartoon images now display the children’s own artwork and pictures.

DE SAM LAZARO: Bowen began by seeking guidance from child development experts. She raised funds in Hollywood where she’d worked as a screenwriter, and from American couples who’d adopted Chinese daughters. She organized volunteer trips to train caregivers and transform the environment in which orphans spent their days. Children who once sat impassively are now in busy pre-schools. Walls that had generic cartoon images now display the children’s own artwork and pictures. Liu Peng Ying: These are like my own children, like my grandchildren. My husband likes children even more than I do. That’s why we decided to apply for this program.

Liu Peng Ying: These are like my own children, like my grandchildren. My husband likes children even more than I do. That’s why we decided to apply for this program.