KIM LAWTON: In Queens, New York, thousands of members of the Chabad Lubavitch movement have come to the gravesite of their spiritual leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson--the Rebbe. They pray and leave notes and wishes, which are usually torn up after they’re offered. Schneerson died in 1994, and two decades later, his followers still want to be near him.

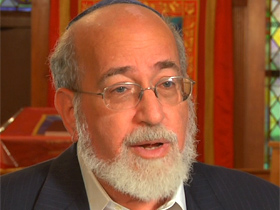

RABBI JOSEPH TELUSHKIN: There is this feeling that the Rebbe had a close connection to God, so people beseech him to intervene, so to speak, on their behalf, and they feel, when they go to his gravesite, they feel that they’re more connected at that holy place.

LAWTON: Rabbi Joseph Telushkin is author of a new biography of Schneerson titled, Rebbe. He documents how Schneerson’s legacy continues to touch Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews, and non-Jews as well. In the 20 years since Schneerson’s death, the Chabad movement has tripled in size. Telushkin, who's Orthodox, but not a member of Chabad, calls Schneerson the most influential rabbi in modern history.

TELUSHKIN: There is no other comparable rabbinic figure in modern times who had such a reach.

TELUSHKIN: There is no other comparable rabbinic figure in modern times who had such a reach.

LAWTON: Schneerson was the seventh Rebbe of the Hassidic Lubavitcher movement which began in the 18th Century. He was born in Ukraine and came to the US in 1941. He settled with other Lubavitchers in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and succeeded his father-in-law as Rebbe in 1951. Schneerson’s personal charisma attracted many, as did his teachings.

RABBI BEREL BELL: The Rebbe took the deepest concepts of Judaism and explained it to the questions that are bothering people today.

LAWTON: Rabbi Berel Bell first encountered Schneerson as a student at Yale University, when he read something the Rebbe had written in a weekly Chabad publication.

BELL: I was absolutely astounded. Just, just in terms of the, the scholarship and the relevance and the importance to living your daily life, I couldn’t believe it. I asked the, the people that I was with, it was a bunch of yeshiva students. I said, “Something like this comes out every week? It would, to me, it seems like somebody’s magnum opus.”

LAWTON: From the beginning, Schneerson’s goal was Jewish outreach, as he put it, “to ignite the soul of every Jew.”

TELUSHKIN: The Rebbe inaugurated the first attempt in all of Jewish history to reach every Jewish community and every Jew in the world. No one was regarded as insignificant and this was very important.

LAWTON: Schneerson instructed his emissaries, known as schluchim, to bring Judaism to every community, no matter how remote. Today, there are more than 4,000 couples running Chabad centers in 49 states and some 80 countries.

LAWTON: Schneerson instructed his emissaries, known as schluchim, to bring Judaism to every community, no matter how remote. Today, there are more than 4,000 couples running Chabad centers in 49 states and some 80 countries.

TELUSHKIN: The Rebbe understood that any one law, any one ritual, any one ethical act, could be that step that could bring someone on a path back to Judaism. And by the way, he thought though that the step had value even if the person didn’t take it further.

LAWTON: Today, Lubavitchers continue carrying out Schneerson’s marching orders, aided greatly by modern technology.

DAVID DENEMARK: When you look online for Jewish institutions, Chabad is probably the first thing you find.

LAWTON: David Denemark is a 23-year-old German university student who says he's faced anti-Semitism in Berlin. He grew up in a completely secular environment, but decided he wanted to reconnect with his Jewish roots. In a Facebook search, he found out about this Chabad Jewish summer Fellowship program in the Catskills.

At gender separated camps, Jewish college or grad students get six weeks of intensive training in sacred texts and mystical teachings. Men learn how to pray and wear tefillin and tzit-tzit, the religious fringes.

DENEMARK: They make you proud to be a Jew and not to be ashamed, go outside with a kippah, show your tzit, don’t be scared, don’t be afraid.

LAWTON: Women also study texts and pray. And they learn practical skills, such as how to make Challah, the traditional bread at Sabbath dinners.

BAILA HECHT: Very often, they are going to other countries exploring other religions and haven’t given themselves an opportunity to discover or explore their own religion.

BAILA HECHT: Very often, they are going to other countries exploring other religions and haven’t given themselves an opportunity to discover or explore their own religion.

LAWTON: Yosefa Jalal’s mother is Jewish and her father, a Pakistani Christian. She came to the program in 2011 and now is a counselor, because, she says, it transformed her spiritual life.

YOSEFA JALAL: I didn’t have much of a Jewish education at all. When I came here I learned a lot of new things and I was amazed, I knew that this was the truth, this was the way that I wanted to follow.

LAWTON: The program began 30 years ago, with Schneerson’s blessing and its leaders believe they are still carrying out his vision.

RABBI SHEA HECHT: Other Hassidic masters and other Hassidic Rebbes said “listen, all you have to do is to study the Torah and teach the Torah.” the Rebbe said no, you have a talent in art, you have a talent in music, you have a talent in medicine, yes, I want you to get the foundations and set yourself up in the foundations of Torah, but then go back to that profession, because everything leads to God.

RABBI CHAIM SCHOCHET (Director, Jewish Summer Fellowship): This is what he loved, you know? Jews from all over having the opportunity to just come, experience in an open environment, in a non-judgmental environment, learning on their own pace, taking it wherever they go.

LAWTON: Program director Rabbi Chaim Schochet says Schneerson was a vibrant presence in his family’s life. As a child, he attended the Rebbe’s popular mass meetings called farbrengen.

SCHOCHET: You know, often people thought it was just charisma, it was just a lot of fluff and singing and dancing and you know, when the Rebbe would no longer be there, it would kind of dissipate. And that’s why they ask 20 years later, “How’s it all going on?” What I think they fail to recognize, it was substance. He was teaching. He was communicating. He was a master teacher.

LAWTON: Telushkin says many of Schneerson’s teachings still have universal appeal.

LAWTON: Telushkin says many of Schneerson’s teachings still have universal appeal.

TELUSHKIN: One was approaching people with nonjudgmental love and not just having a love of people, but it always remained focused on the individual. Anything worth doing is worth doing now. The Rebbe would not delay things. The Rebbe also had the capacity to disagree without being disagreeable and what was the secret of that? He focused on what he held in common with other people. That’s exactly what most human beings don’t do.

LAWTON: For Jews, Schneerson stressed the importance of doing good deeds and fulfilling commandments in order to usher in redemption and the coming of the Messiah, Moshiach. The movement still believes that.

JACOB ZIEPER: Is the Moshiach part of my world? Absolutely. I believe that any one single deed any person does could be the deed that brings Moshiach.

LAWTON: Because of his spirituality and popularity, some Chabad followers saw Schneerson himself as a potential Messiah, and that belief persists in some quarters.

TELUSHKIN: To be truthful, there are some Chabadniks, some people within his movement, who believe that he will return from the dead. They’re hoping that when the dead are revived, he’ll be one of them and he’ll be revealed as the Messiah. I don’t see that affecting peoples’, any peoples’ behaviors on a day-to-day basis. When that day will come that the Messiah comes, we’ll find out. But I think it has greatly receded in significance.

LAWTON: Although several of Schneerson’s close associates provide administrative leadership for the Chabad movement, no new Rebbe was named after his death.

TELUSHKIN: What’s also significant is that the movement has undergone its greatest growth without a leader. Maybe the time will come when the movement will find a figure who seems to have that same unifying charisma that the Rebbe had, but in the meantime, it’s working.

TELUSHKIN: What’s also significant is that the movement has undergone its greatest growth without a leader. Maybe the time will come when the movement will find a figure who seems to have that same unifying charisma that the Rebbe had, but in the meantime, it’s working.

LAWTON: Many Lubavitchers say Schneerson continues to lead them through his teachings. They believe, as Chabad’s key text, the Tanya, teaches, the essence of a Rebbe doesn’t end with death.

BELL: It says in Tanya that the influence is even stronger… is even stronger after the physical presence is not visible than before. Because during the physical lifetime, the soul was limited to a body. Afterwards, the soul is free to affect things without the constraints of a body.

LAWTON: Lubavitchers also say they are united by the knowledge that they still haven’t achieved the mandate Schneerson gave them, to reach every Jew.

SCHOCHET: One Jew lost is one Jew too many. We have to reach out. Children in camps, students on their campuses, communities. Build synagogues and community centers. Wherever Jews are and whatever stage and whatever country, we have to reach out to them and bring them on board.

LAWTON: But it’s not an easy task. Growing numbers of US Jews, especially young Jews, describe themselves as religiously-unaffiliated.

TELUSHKIN: How can you find what Judaism can still offer people to give meaning to their lives? In the final analysis that’s what human beings are looking for, they want to feel that they’re part of something more important than just themselves. How do you do it? And that’s what the challenge will be.

LAWTON: Chabad members believe that challenge is precisely why Schneerson’s legacy is more important than ever. I’m Kim Lawton in New York.

TELUSHKIN: There is no other comparable rabbinic figure in modern times who had such a reach.

TELUSHKIN: There is no other comparable rabbinic figure in modern times who had such a reach. LAWTON: Schneerson instructed his emissaries, known as schluchim, to bring Judaism to every community, no matter how remote. Today, there are more than 4,000 couples running Chabad centers in 49 states and some 80 countries.

LAWTON: Schneerson instructed his emissaries, known as schluchim, to bring Judaism to every community, no matter how remote. Today, there are more than 4,000 couples running Chabad centers in 49 states and some 80 countries. BAILA HECHT: Very often, they are going to other countries exploring other religions and haven’t given themselves an opportunity to discover or explore their own religion.

BAILA HECHT: Very often, they are going to other countries exploring other religions and haven’t given themselves an opportunity to discover or explore their own religion. LAWTON: Telushkin says many of Schneerson’s teachings still have universal appeal.

LAWTON: Telushkin says many of Schneerson’s teachings still have universal appeal. TELUSHKIN: What’s also significant is that the movement has undergone its greatest growth without a leader. Maybe the time will come when the movement will find a figure who seems to have that same unifying charisma that the Rebbe had, but in the meantime, it’s working.

TELUSHKIN: What’s also significant is that the movement has undergone its greatest growth without a leader. Maybe the time will come when the movement will find a figure who seems to have that same unifying charisma that the Rebbe had, but in the meantime, it’s working.