Mark G. Toulouse: The Religion of the Republic

The conventions are over. Truckloads of trash have found their way to landfills, despite best efforts to “go green.” Massive sets of Democratic Doric columns and the 51 foot by 30 foot high-definition screen of the Republicans, composed of 561 Hibino four-millimeter Chroma LED panels and often filled with shots of an American flag flapping in the breeze, have all been returned to wherever it is such things go. Pundits, left and right and indifferent, have offered their takes on anything and everything. Religion and the conventions has been a popular theme.

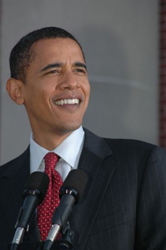

For the first time in their history, the Democrats seemed to do “religion” right, reflecting Obama’s firm belief that all religious voices belong in debates concerning public policy. Appointing a Pentecostal minister as the chief executive officer of the convention brought new religious twists, including a rousing interfaith service on Sunday afternoon and four “faith caucuses” held throughout the convention. Both Republicans and Democrats began and ended each session with prayer from a variety of religious leaders, though the Democrats, as was especially true of their delegations as a whole, held a decided edge in the diversity department. The important speeches all ended with the obligatory “God bless America” or similar ritualistic catch-phrases meant to communicate the piety of our great country. Speeches were carefully crafted to include meaningful religious references where appropriate, but unplanned references crept in here and there. In addition to the two references to God scripted in his VP acceptance speech, Joe Biden added four impromptu, colloquial, perhaps even profane references in actual delivery (not quite the pious references Democrats had in mind), as in “God, I wish that my dad was here tonight.” Family values got their pitch as well, as both parties highlighted (exploited?) the children, spouses, and parents of their candidates.

For the first time in their history, the Democrats seemed to do “religion” right, reflecting Obama’s firm belief that all religious voices belong in debates concerning public policy. Appointing a Pentecostal minister as the chief executive officer of the convention brought new religious twists, including a rousing interfaith service on Sunday afternoon and four “faith caucuses” held throughout the convention. Both Republicans and Democrats began and ended each session with prayer from a variety of religious leaders, though the Democrats, as was especially true of their delegations as a whole, held a decided edge in the diversity department. The important speeches all ended with the obligatory “God bless America” or similar ritualistic catch-phrases meant to communicate the piety of our great country. Speeches were carefully crafted to include meaningful religious references where appropriate, but unplanned references crept in here and there. In addition to the two references to God scripted in his VP acceptance speech, Joe Biden added four impromptu, colloquial, perhaps even profane references in actual delivery (not quite the pious references Democrats had in mind), as in “God, I wish that my dad was here tonight.” Family values got their pitch as well, as both parties highlighted (exploited?) the children, spouses, and parents of their candidates.

Democrats hope their efforts to take faith seriously will close the perceived “God gap” between the political parties. A Pew Forum poll released the week before Denver indicates that Obama has made some progress in closing the gap. Thirty-eight percent of Americans (it was 26 percent just two years ago) find the Democrats generally friendly toward religion. But they are still behind the 52 percent of Americans who see the Republicans that way. If Democrats can pick up a few percentage points among white Catholics and evangelicals, the election would be much harder for Republicans to win in November.

To be honest, I’m less interested in these kinds of analyses of religion and the conventions than I am in how the conventions actually demonstrated a religious vision of America and its role in the world. This slant on religion and the political parties has been largely ignored by most. In what ways did the conventions reveal how parties and candidates think about America religiously, something Sidney Mead described as “the religion of the Republic”? Mead, an American religious historian who died in 1999, argued in his book THE LIVELY EXPERIMENT that America itself possessed a transcendent and universal religion that is “articulated in terms of the destiny of America, under God, to be fulfilled by perfecting the democratic way of life for the example and betterment of all mankind.” These conventions demonstrated well that American civil religion, or the religion of the Republic, still moves many Americans to convention ecstasy, including Americans who claim to take Christian faith, or other traditional faiths, so seriously.

For the Democrats, signs proclaimed a commitment to “change you can believe in.” But the theme of the convention consistently emphasized a need to renew the “promise of America.” America is the one “glorious nation” under God “where anyone who works hard enough can make the most of their God-given potential.” “This,” proclaimed New York Governor David Paterson, “is the promise of America.” Throughout, Democratic leaders sounded the theme that the essential promise of America (and therefore, the country’s mission) is threatened by the fiasco of the last eight years of Republican leadership. From states like Missouri, Iowa, West Virginia, and others the convention heard speeches emphasizing how hardworking people have survived the challenges of life to make it, and how the past decade has threatened to take away their hopes at keeping their slice of the “American dream” alive. In this way, the Democrats appealed to the self-interest of every American. They spoke of an America focused on individual accomplishment and advancement. Hillary Clinton hammered the theme well: “I ran for President to renew the promise of America. To rebuild the middle class and sustain the American Dream. . . .We need leaders once again who can tap into that special blend of American confidence and optimism . . . who can help us show ourselves and the world that with our ingenuity, creativity, and innovative spirit there are no limits to what is possible in America.” Bill Clinton echoed these phrases with his own as he stressed that the “American Dream is under siege at home.”

In his inspiring address, Obama spoke of his parents who believed in an America where “their son could achieve whatever he put his mind to.” “It is that promise that has always set this country apart — that through hard work and sacrifice each of us can pursue our individual dreams but still come together as one American family, to ensure that the next generation can pursue their dreams as well.” The mission of America, for Democrats, is to keep “the American promise alive.” Thus, if threatened from the outside, Democrats can and will take the military actions necessary to secure the American future, to keep America “that last, best hope for all who are called to the cause of freedom, who long for lives of peace, and who yearn for a better future.” In other words, America is the great example for the world and must be protected, but its promise must never be abused or misused. Bill Clinton spoke a one-liner that said it best: “People the world over have always been more impressed by the power of our example than by the example of our power.” Obama summarized “the promise of America — the idea that we are responsible for ourselves, but that we also rise or fall as one nation; the fundamental belief that I am my brother’s keeper; I am my sister’s keeper. . . . Individual responsibility and mutual responsibility — that’s the essence of America’s promise.” Then, continuing his use of biblical allusions to apply to Americans, Obama closed his speech with “Let us keep that promise — that American promise — and in the words of Scripture hold firmly, without wavering, to the hope that we confess.” Is he talking of the hope Christians have in Christ? No, here the hope is the one that all Americans share in the promise of America — the hope that we can succeed, have a good life, and teach the world how to live by our example.

In his inspiring address, Obama spoke of his parents who believed in an America where “their son could achieve whatever he put his mind to.” “It is that promise that has always set this country apart — that through hard work and sacrifice each of us can pursue our individual dreams but still come together as one American family, to ensure that the next generation can pursue their dreams as well.” The mission of America, for Democrats, is to keep “the American promise alive.” Thus, if threatened from the outside, Democrats can and will take the military actions necessary to secure the American future, to keep America “that last, best hope for all who are called to the cause of freedom, who long for lives of peace, and who yearn for a better future.” In other words, America is the great example for the world and must be protected, but its promise must never be abused or misused. Bill Clinton spoke a one-liner that said it best: “People the world over have always been more impressed by the power of our example than by the example of our power.” Obama summarized “the promise of America — the idea that we are responsible for ourselves, but that we also rise or fall as one nation; the fundamental belief that I am my brother’s keeper; I am my sister’s keeper. . . . Individual responsibility and mutual responsibility — that’s the essence of America’s promise.” Then, continuing his use of biblical allusions to apply to Americans, Obama closed his speech with “Let us keep that promise — that American promise — and in the words of Scripture hold firmly, without wavering, to the hope that we confess.” Is he talking of the hope Christians have in Christ? No, here the hope is the one that all Americans share in the promise of America — the hope that we can succeed, have a good life, and teach the world how to live by our example.

The Republican “religion of the Republic” stressed other commitments. While the Democrats emphasized the disastrous economy and the loss of America’s standing as example across the world, the Republicans emphasized placing “Country First.” While they also sounded well the note that all Americans should prosper, they emphasized that Obama was not tough enough to insure America’s safety. He would, warned Mike Huckabee, “continue to give madmen the benefit of the doubt.” Fred Thompson told the convention that John McCain would be the kind of president “who feels no need to apologize for the United States of America.” Republicans believe in an America whose mission is threatened more by external forces than internal economic problems. “Our country is calling,” Thompson reminded listeners. President Bush emphasized the “dangerous world” we live in and the need for a president who will protect America by staying “on the offense [and] stop attacks before they happen.” Rudy Giuliani touted McCain as the “man who believes in serving a cause greater than self-interest [then, going off-script] and that cause is the United States of America — America comes first!” McCain’s address to the convention offered a kind of religious testimony. In moving terms people often use when talking of their experiences of God, he said that the prison in Hanoi changed him: “I wasn’t my own man anymore. I was my country’s.”

In the well-established tradition of President Bush and any self-respecting religion, Republicans spoke often of good and evil and America’s representation of the good in the world. Romney said it clearly: “Republicans believe that there is good and evil in the world. . . John McCain hit the nail on the head: radical violent Islam is evil, and he will defeat it!” In facing the threat posed by radical Islam and all other evils, John McCain and Sarah Palin will “keep America as it has always been — the hope of the world.” This Republican hope for the world does not rest in the American example of living freely, but rather in its proactive expansion of freedom across the world. Republicans are, Giuliani exclaimed, the party that “believes unapologetically in America’s essential greatness.” Palin attacked Obama as one who “wants to forfeit” in Iraq and is “worried that someone won’t read [al Qaeda] their rights.” But McCain possesses “the special confidence of those who have seen evil, and seen how evil is overcome.” Though she did not do so at the convention, she told ministry students meeting at her former church in Anchorage that American troops in Iraq are serving in a “task that is from God.” In the Republican understanding of the religion of the Republic, little seems to separate America and expansion of freedom from good, and the threats to these from evil. While McCain’s speech was much more subdued than Palin’s and underscored that government should “make sure you have more choices to make for yourself,” he claimed to “know how the world works” and to “know the good and the evil in it.” Where Democrats are running to renew the promise of America and its example, Republicans are running, in McCain’s words, “to keep the country I love safe,” and to “see the threats to peace and liberty in our time clearly and face them.”

These are two very different versions of the religion of the Republic. One emphasizes the life of the ordinary American and the divine right existing in the promise of America to fulfill all God-given potential. It is largely a religion aimed at self-interest. As Hillary Clinton said, “it comes down to you — the American people, your lives, and your children’s futures.” In this version, America serves as an example of freedom to the world, the nation where human beings can thrive and succeed and live the life that God intended them to live in harmony and peace with one another — a nation that models what God intends for all nations. Americans can fight external enemies, if need be, to preserve the promise of the nation, but they are not proactively looking for a fight. No word about how the American drive for success, even at the individual level, affects the rest of the world, or how the American freedom to consume impacts resources for everyone else.

The other version highlights evil in the world and is confident that America is the divine agent called to fight it, a nation on the offensive. Here the nation is the church, the place where God is present and active in mission, but it is clearly the nation, on God’s behalf, that defeats evil and brings freedom and democracy, by any means necessary, to the rest of the world. Like the Democrats, Republicans can also quote the Bible, as President Bush did at Ellis Island on the first anniversary of 9/11 when he said, “This ideal of America is the hope of all mankind. That hope drew millions to this harbor. That hope still lights our way. And the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness will not overcome it. May God bless America.” Without acknowledging it, President Bush used John 1:4, a passage describing the Word of God, in whom “was life, and the life was the light of all people,” to refer to the hope of America and its role as a light to the nations. This messianic, and very religious, understanding of America contains profound, and usually tragic, implications for all other peoples and nations in the world.

So what are good people of faith to do with these versions of the religion of the Republic? Of the two versions, I’m more drawn to the former than the latter, to an understanding of example rather than imperial mission. But from a Christian perspective I am put off by its constant appeal to self-interest. I genuinely miss some expression of the prophetic vision of Jimmy Carter’s understanding of the “spiritual malaise” that continues, I think, to affect American life. But others will have to make their own choices. My hope is that they will do so with the full recognition that, while both parties try to convince us that they are hospitable to people of faith, each is actually proposing a competing religious vision to those that the traditional faiths espouse.

— Mark G. Toulouse is professor of American religious history at Brite Divinity School and the author of GOD IN PUBLIC: FOUR WAYS AMERICAN CHRISTIANITY AND PUBLIC LIFE RELATE (Westminster John Knox Press, 2006). Beginning January 1, he will be principal and professor of the history of Christianity at Emmanuel College, Victoria University, in the University of Toronto.