DAVID TERESHCHUK, correspondent: A Baptist service in Harlem, New York—at the First Corinthian Baptist Church (FCBC), in fact, that is deeply rooted in the black Baptist tradition. But look closely, and there’s a perhaps surprising number of white faces.

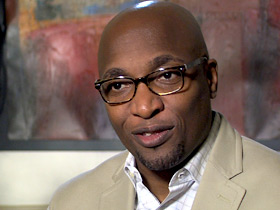

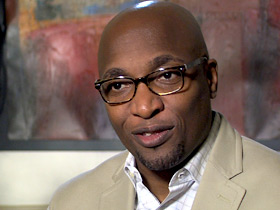

REV. MICHAEL WALROND (Senior Pastor, FCBC): We’ve seen a rise in the amount of whites who’ve joined the church. It’s still not a large percentage, but enough to notice.

TERESHCHUK: And growing?

WALROND: Oh, yes, growing. It’s growing every week.

TERESHCHUK: What’s happening at First Corinthian varies strikingly from the conventional picture of America at prayer on a Sunday morning.

WALROND: I remember years ago, when I was in school, hearing a quote from Dr. King when he said “eleven o’clock is the most segregated hour in the United States.”

TERESHCHUK: Though having white people among its worshippers may be fairly new, First Corinthian is accustomed to white visitors—tourists who will often fill the spectators’ balcony. The church is, after all, a landmark in a world-famous neighborhood: the iconic center of much African-American culture and history, seedbed of the Harlem Renaissance. Nowadays, though, the district is quite altered and its population becoming more mixed. One sign of the times is the housing stock getting visibly changed by gentrification.

Scott Burrows is a local public schoolteacher who got his first taste of Baptist worship at another African-African church, and now, after testing a range of denominations, he’s becoming a regular at First Corinthian.

SCOTT BURROWS: I tried an Episcopal church and a Catholic church and some different church settings. I can’t explain why I didn’t feel what I feel here.

TERESHCHUK: Though Burrows was attracted by Baptist preaching, he still hesitated for a while, feeling discomfort and questioning himself.

BURROWS: How can I be part of this congregation? My background is so different, my culture, my heritage is such a different experience. And they reassured me that we’re here, you know, in Jesus’ spirit, and if we’re here to worship together then it’s a good thing.

TERESHCHUK: Once given that reassurance, Burrows sensed a contrast with what he had previously known of white Christianity.

BURROWS: When I went to churches where there were more people that looked like me that I feel that it’s less of a deep experience. And here in a Baptist setting, and in this traditionally African-American setting, the pastor is helping me to encourage me to connect with God directly.

TERESHCHUK: Though feeling God-connected, Burrows is still a conspicuous rarity in these pews, and some discomfort remains for him, though he doesn’t now regard it as a bad thing.

BURROWS: I’m sure it’s the same awkwardness than many African Americans feel when they’re in a big group of white people, and there are only one or two of the black people present. So it’s a good experience. I think it’s a kind of humbling and empathic experience.

TERESHCHUK: Robbin Gust, a retired transit system employee, has been a member at First Corinthian for three years, and right from the start, she says, she never felt any awkwardness.

ROBBIN GUST: I have lived on 116th Street for 22 years. I never walked in the church. I never had any interest in going to church where I live. And one day I just came in and never left. I joined the church the day I came.

TERESHCHUK: Gust takes a full part in the church’s work, singing in the choir and helping with its prison ministry.

GUST: No matter where I go everyone’s, like, “Hey, Robbin.” So it’s just really nice to be part of a great community. I don’t feel like I’m in the, you know, like a black community, a black church. I’ve never thought about it like that. The church is so diverse with so many different walks of life that that was never even—it never even crossed my mind to think that.

TERESHCHUK: First Corinthian’s congregation has been growing in overall numbers ever since Michael Walrond became senior pastor a decade ago. He’s emphasized an outward-looking, socially involved view of the gospel. He believes this is what helps to broaden the church’s appeal—not any deliberate targeting of specific demographics.

WALROND: I don’t think to myself that today I must preach a message so that whites can join, or today I must preach a message so that blacks can feel affirmed. I preach a message so the gospel can be realized and actualized. That is a message that knows no racial boundary. White, Black, Latino, Asian—no matter who you are we all believe, we all cry, we all have pain, we know what it is. And when we begin to speak to the existential issues that bind us together, I think people find a home and a place of common ground.

TERESHCHUK: Willa Rose Johnson is among the newer white element in the church, and she has even gone on to become one of the church’s ministers.

WILLA ROSE JOHNSON: I was surprised, because I didn’t see myself in an African-American church. I always grew up in a predominantly white church, just natural—you know, I’m white, my family’s white, so it just—that’s just always been my context.

TERESHCHUK: Originally from Georgia, Johnson found FCBC, as First Corinthian is often known, after she came to New York as a theology student.

JOHNSON: FCBC’s the place that makes everyone feel comfortable. Really, it’s very—it’s quite remarkable. It’s not only just comfort; it’s what I call the FCBC magic. I did not expect, when I first started worshipping in FCBC, that I would work here.

TERESHCHUK: When she graduated, a job opportunity came up here, but she wasn’t sure about applying for it.

JOHNSON: I did approach Pastor Mike, and I was, like, “Is this okay?” I mean, I don’t want to be encroaching on a space that’s a safe space for African Americans.

TERESHCHUK: Johnson was told she’d be welcome as a staff member, and she now runs the church’s outreach work, engaging with the surrounding community and its problems.

JOHNSON: There are particular challenges to Harlem: gentrification, rising cost of housing. There’s more poverty here than there may be in other parts of New York.

TERESHCHUK: And it hasn’t been hard for you as a white woman to do that engaging?

JOHNSON: You know, it might have been hard for other people with whom I’m engaging, but it hasn’t been super hard for me. Yes, I’ve become increasingly more self-aware, I would say. I reflect on it a lot. I’ve thought a lot about what it means to be white. But you really see that human pain has no color. We’re all one paycheck away from homelessness, potentially, we’re all one tragedy, one pain away from falling apart as people.

TERESHCHUK: Back in the church itself, how has the black majority reacted to whites coming to worship within a religious tradition known for expressing pride in black identity? Could a growing white presence dilute that identity?

WALROND: I have not heard any complaints. Our purpose statement is on the wall, and it says that we are commanded by God to love beyond the limits of our prejudices. One challenge we had is that we had to help some of our leaders realize that all the persons who are white who come here are not tourists.

TERESHCHUK: There’s also been a lingering doubt that, for some whites, their experience might still be that of an observer more than a full participant.

JOHNSON: There’s a dangerous line between coming to worship and then looking at other—someone else’s religiosity as entertainment.

TERESHCHUK: But for the increasing number of worshipping whites who feel entirely at home in FCBC, that’s simply not an issue.

BURROWS: I’ve come here for the purpose of praising and worshipping and being a part of the congregation, and not coming here for the spectacle or the novelty or a show. I feel centered, I feel balanced, I feel like I’m in a safe place, and I did the right thing to get out of bed and get here this morning.

TERESHCHUK: Undoubtedly Harlem is changing, First Corinthian is changing. But with all the evolving change that the church is committed to, it is also determined to stay true to its roots and its character.

WALROND: As we continue to walk in the identity that God has shaped us in, yes, there’ll be others who will join, others who will feel compelled to be a part of this movement, part of this place. There’s something beautiful about the culture and the history of Harlem. In the midst of influx of persons of all backgrounds who find themselves coming to Harlem, there’s something unique. That will not change. That is what makes Harlem Harlem.

TERESHCHUK: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is David Tereshchuk in Harlem, New York.