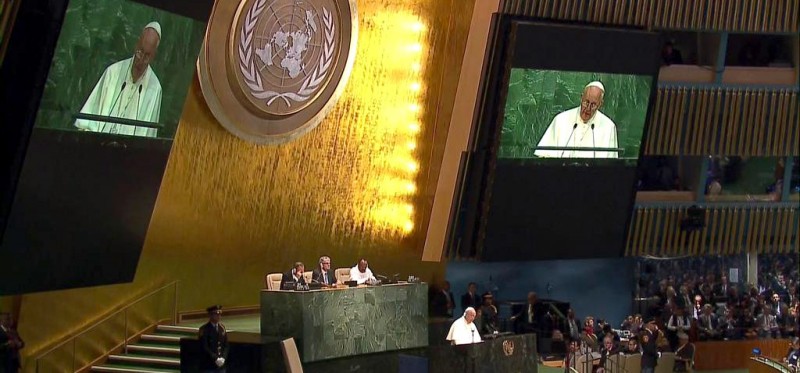

On Friday (September 25), Pope Francis spoke at the UN to the people of the world, just as yesterday (September 24), to use his words, he initiated dialogue with the people of the United States. In both cases he drew on people’s history and most noble aspirations, in one case by reference to iconic national leaders, in the other by reference to a founding document, the UN Charter.

In Washington, for a few hours, he helped transcend polarized politics; in New York, again for a moment, he transcended discouragement, even cynicism, about the now 70-year-old dream of peace through international cooperation. In both cases Pope Francis recognized disagreements and acknowledged discouragement but he deliberately enlisted himself and the Church in the work of building solidarity and practicing shared responsibility. Before Friday’s talk he urged an enthusiastic gathering of UN staff to “care for one another” so that in their diversity and shared commitment to the global common good they might embody the hopes of humanity for a future of justice and peace. In many ways his talk asked everyone to join in that care for one another and the world.

In New York as in Washington, the pope touched gently but truthfully on hot-button issues. He placed at the center environmental deterioration and the “exclusion” of massive numbers of poor and marginalized people. Political leaders are gathering at the UN this weekend to renew and extend their millennial commitments to overcoming extreme poverty. Pope Francis praised this work for sustainable development but consistently used the word “excluded” rather than “the poor” to draw attention to the need to reduce inequalities of power as well as income and wealth.

Echoing persistent criticism of top-down development strategies, Pope Francis condemned “the relentless process of exclusion” often consequent on the search for prosperity. He was particularly critical of international financial institutions and “oppressive lending systems.” Instead, he insisted that everyone, regardless of wealth or social status, should have the power to participate in building a just and sustainable political economy. People should be “the dignified agents of their own destiny.” This reflects his commitment to “accompanying” those on the periphery and his calling to make their voices heard in citadels of privilege.

Pope Francis took note of many other issues: widespread violence, religious extremism and assaults on religious liberty, the “scourge” of war and the scandal of trade in arms, the persistent evils accompanying the drug trade and the poorly fought “war” on drugs. He spoke out for the abolition of nuclear weapons and praised the most recent agreement to limit proliferation. He gave thanks for UN peacemaking and peacekeeping efforts, and urged reform to bring greater equity to UN decision-making, noting particularly the Security Council.

Understandably, but unfortunately, the UN talk will probably receive less attention in the US than the speech to Congress. The Washington talk was quickly translated into familiar categories of problem-solving rather than partisan divisions. The papal-visit story, as told in the media, usually centers on personalities rather than structures and ideas. It is hard to penetrate our American parochialism. We assume domestic problems can easily be resolved if we put divisions aside, and global problems, even terrorism, pose no immediate threat to our daily life.

On the periphery things look different. At the UN, the pope from the global south spoke with passionate urgency about problems that make life in much of the world tenuous and uncertain. His were terms familiar to thoughtful people in countries lacking the military, economic, or political resources to “defend life at every stage of development.” For such people and countries, international law and multi-national cooperation are essential; unilateral action by powerful nations, even if well-intentioned, is dangerous; and international institutions under the influence of global powers, economic and cultural as well as political, are regarded with suspicion. Those assumptions underlie the pope’s comments on global politics and inform his remarkable effort to bring everyone, at the centers and edges of contemporary life, into the process of making history.

The pope has won affection and attention by stepping outside the religious boundaries of the Church and taking seriously the joys and hopes of the entire human family. He invites other people of faith to do the same. He also draws attention because the Argentine pope has chosen to stand outside the framework of nations and classes to care first of all for our common home, the earth, and for our brothers and sisters without power, the excluded. He invites all of us to do the same.

We Americans rightly worry about political polarization, but the UN speech would suggest the need to worry as well about things we agree on, like the need for enough unilateral military power to protect our security and enough economic power to protect our material interests. The global common good, sustainability and human rights may draw nods of the head but always seem to end with what Pope Francis called “declarationist nominalism,” words we have no intention or capacity to act upon. We make much of political freedom, religious liberty, and free markets, but even modest suggestions by politicians that we might rely on the “tireless work of negotiation, mediation, and arbitration” to achieve our goals would cost them the next election.

Pope Francis before Congress challenged Americans to live up to the ideals of solidarity, inclusion, care for the excluded, and dialogue about differences represented by Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton. In New York, he called upon people everywhere to make the same commitment to care for the global common good as those UN workers he greeted before his speech. At the end of the UN speech he warned against “idle chatter” and called for action, political will. That seems an appropriate call to the world leaders who will gather at the UN this weekend, but in the end it is a call to everyone, especially those of us who are no longer excluded and now bear a full share of responsibility. As Pope Francis encountered people at every stop, he seemed to suggest by his smile and his warmth that taking up that responsibility might even make us happy.

David O’Brien is professor emeritus of Roman Catholic studies at the College of the Holy Cross.