In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

A Year with the Quran

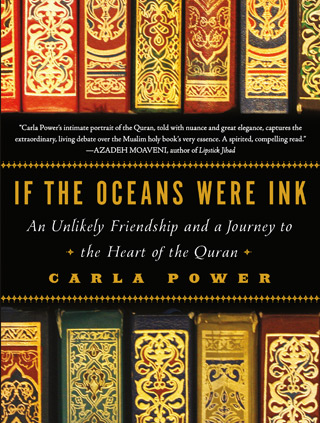

American writer Carla Power and madrasa-trained Sheikh Mohammad Akram Nadwi debated Islam’s holy book in search of interfaith understanding. She has written about the experience in her new book If the Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran. “People are going back to the basic texts, and they’re stripping away centuries of culture and tradition and looking for what they see at the heart of the religion,” she says.

…

Read an excerpt from If the Oceans Were Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to the Heart of the Quran by Carla Power:

My year with my own sheikh and the Quran provided me with many moments of grace. I found comfort in how small I felt reading the text, as when I considered the images of the “lord if the heavens and the earth and everything in between, and Lord of all points of the sunrise.” Even as a nonbeliever, I still found myself taking refuge in the Quran classes as a clam inlet from daily life. The sheikh’s disregard for all the measurements of getting and spending was soothing. Yesterday’s close on Wall Street, the exam score or dress size, even happiness itself; all were nothing next to the fact that from God we com and to God we return. The constant reminders of one’s own puniness and powerlessness were strangely bracing. When my mother died, I remember thinking how sensible it was, the Muslim practice of saying “Inshallah,” or “God willing,” after every plan, every promise, no matter how minor, since only God can be sure whether next Wednesday’s lunch date will indeed be kept. It was a comfort, in a season of grief, to hang out with a community that honored this world’s certainties.

…

For the sheikh, existence was a circle with God at its end, beginning, and every point in between. From Allah he has come, and to Allah he will return….Everyday circled back to his God. Thirty-five times a week—and often many more—he returns to prayer. In standing, kneeling, bring his forehead to the earth, then standing again, his attention returns to his origins and destination, which are one and the same. On good days, prayer could feel like returning to “the arms of your mother, when you are a child,” he said.

For the sheikh, existence was a circle with God at its end, beginning, and every point in between. From Allah he has come, and to Allah he will return….Everyday circled back to his God. Thirty-five times a week—and often many more—he returns to prayer. In standing, kneeling, bring his forehead to the earth, then standing again, his attention returns to his origins and destination, which are one and the same. On good days, prayer could feel like returning to “the arms of your mother, when you are a child,” he said.

…

When I began my Quran lessons, I assumed, with pert certainty, that I would read a book through and learn what was inside it. The first clue that I couldn’t had arrived during that first lesson. “Ah, but is it a book?” the sheikh had asked. I’d patted my paperback, clueless as to what he meant. I’d come a long way from earliest encounter with the Quran, but I still hadn’t understood that it was far more than a much-revered book. Over the course of the year, I began to see that the Quran was not merely a set of pages between two covers. Calling it a book, something one can read from beginning to end, embalms it in expectations. It was just another way of limiting it into something small: an amulet, a manifesto, an instruction guide, a political tool. In the life of a Muslim like [Sheikh] Akram, its meaning is much more diffuse. So, too, is the Quran’s reach in Muslim societies, where its words blare from mosque loudspeakers issue from radios and CDs, or hang on necks or walls. Grasping at what the Quran might be, I can only settle on the metaphor of return. It is a place to which the faithful return, again and again.

Much as they do to prayer. Scientists who have studied the postures of Muslim prayer have found they encourage calm and flexibility. Standing straight in the opening stance, they discovered, strengthens musculature. Bowing stretches out the lower back and hamstrings. The pose of sitting after prostration keeps joints mobile. Akram’s prayers have rendered him culturally supple, too, stretching his humanity in surprising ways. The act of return—to his prayer mat, to his Quran and his classical texts—has often afforded an expansion of his worldview, not a restriction of it.

…

When I asked the sheikh how I could deepen my understanding, his answer invariably echoed the command that Muhammad heard: “Read.” Keeping reading the Quran, he told me at our last lesson. Read it, and read it again. Return.