KIM LAWTON, correspondent: This is the Grand Entry procession at the annual Tekakwitha Conference. Native American Catholics from more than 100 indigenous tribes across the US and Canada have gathered to show their devotion to Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th Century convert to Catholicism and the Church’s first Native American saint.

SISTER KATERI MITCHELL (National Tekakwitha Conference): After all these centuries, the love of her people has seemed to just have been a contagious type of love that has swept right across the country.

LAWTON: Saint Kateri or as some call her, Saint Ka-TERI, is a vivid symbol of the Catholic Church’s complicated relationship with indigenous people. For many, she represents the diversity of a church that has been embraced across racial and cultural lines.

REV. MAURICE HENRY SANDS (Black and Indian Mission Office): It means a lot to have somebody like St. Kateri who is being held up by the whole Catholic Church, as well as someone who is recognized and respected and greatly esteemed throughout the whole world.

LAWTON: But for some Native Americans, she represents the pain of colonization and missionary activities that were seen as destroying indigenous culture and religion.

KENNETH DEER (Indigenous World Association): We believe the Creator gave everybody their own spirituality so if he gave it to Europeans or to people in the Middle East, that’s for them, you know. And not for us.

LAWTON: Nicknamed the “Lily of the Mohawks,” Kateri was born in the mid-1600s in what is now New York State. She lived in a Mohawk village that was part of the Iroquois Confederacy.

PROF. ALLAN GREER (McGill University): There’s a series of epidemics that pass through this part of the world. Terrible small pox that when she’s six years old, she is very ill with. It has a permanent effect on her health. She loses both her parents.

LAWTON: Allan Greer is professor of history at McGill University in Montreal and author of the book, Mohawk Saint. He says as a young woman, Kateri began studying with Jesuit missionaries in the area and decided to become baptized.

GREER: There’s more specific detailed information on her life than on any Indian person of North, South, Central America at the time of initial encounter with Europeans, so she is uniquely well-documented.

LAWTON: The Jesuits documented much of Kateri’s life in their journals. They described how, after her conversion, the young woman moved to the Jesuit mission at Kahnawake, near what is now Montreal, where there were many native converts.

GREER: What made her stand out along with several other young Mohawk women is she practiced an extreme form of what religious scholars would call mystic asceticism—religious practice that involves inflicting deliberate pain and discomfort on the body as a way of empowering the spirit.

LAWTON: Kateri’s health was always weak, and she died in 1680, when she was around 24 years old. Almost immediately stories about her charity, devotion, and purity began to spread, as did stories of miracles. Leona Gonzales of the Tuscarora tribe in New York recounts one miracle story involving the small pox scars on Kateri’s face.

LEONA GONZALES: She’s dying, and she mentions, ‘Jesus I love you.’ And according to the journals written in French by the Jesuits, the pox marks all disappeared from her.

LAWTON: An effort to see Kateri officially recognized as a saint was launched in 1884, but the church’s complicated process for sainthood usually takes decades. In 2011, the Vatican certified the final required miracle: a young boy of Native American descent, Jake Finkbonner, was cured of a life-threatening case of flesh-eating bacteria after family and friends prayed that Saint Kateri would intercede with God for him. One of those praying at Jake’s bedside was Sister Kateri Mitchell. She is executive director of the National Tekakwitha Conference. Mitchell says Catholics across the country have formed Kateri prayer circles.

MITCHELL: They are really a powerhouse of prayer when they gather. So many of our people have received multiple favors and praying through her intercession and many who have received a lot of healing.

LAWTON: Gonzales says Saint Kateri interceded for her as well, although it wasn’t officially recognized as a miracle.

GONZALES: I had thyroid cancer 14 years ago and with her help it’s gone. Surgery removed all of thyroid and all of the cancer.

LAWTON: When Kateri was canonized at the Vatican in October 2012, Gonzales and several family members were there.

GONZALES: She’s always been our saint. Always.

LAWTON: But for many Native Americans, the issue of indigenous people converting to Catholicism remains a sensitive one. During his visit to the US, Pope Francis canonized Father Junipero Serra, an 18th Century Spanish missionary who brought Christianity to California. Some Native Americans protested the canonization, arguing that missionary efforts were tied to colonization, which was devastating to indigenous cultures.

DEER: The problem was is that Christians weren’t honest. And that’s how we lost our land. They lied to us and they also felt superior to us and betrayed us and I think they betrayed our trust and they used religion.

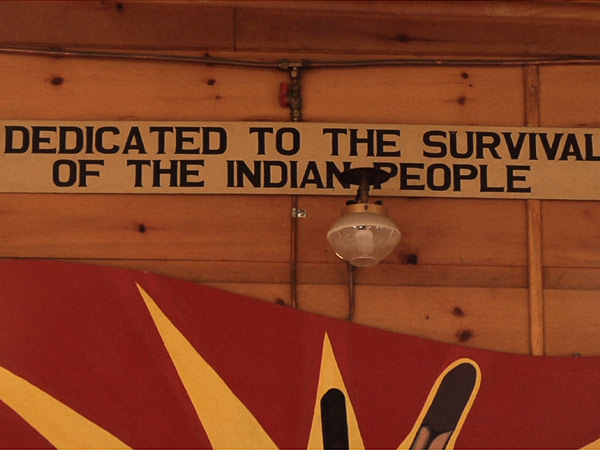

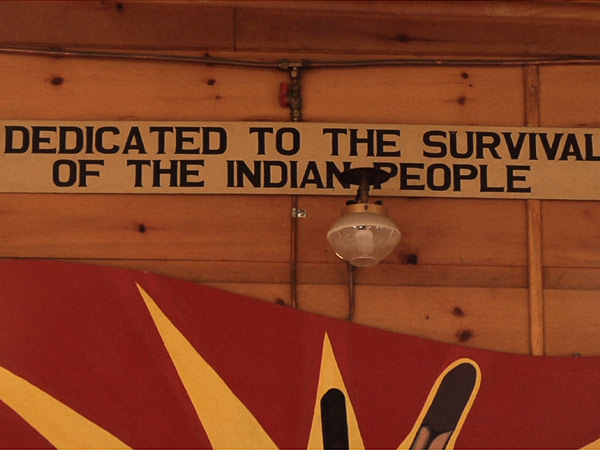

LAWTON: In many areas, tensions persist between Catholicism and traditional native religions, which are often practiced in a longhouse.

DEER: At a very early age, around 12 or 13 years old, I was an altar boy at the time, and I was sitting on the altar one day during Mass and I was looking around and I was wondering to myself, ‘what am I doing here?’ you know. There’s nothing in the church you know in the mass or anything that I could identify with as a young Mohawk.

LAWTON: But Native American Catholics take a more nuanced view. Father Maurice Henry Sands directs the Black and Indian Mission Office, founded by the US Catholic bishops.

SANDS: There have been lots of negative things that have also come along with the Europeans who came that also impact us to the present day. As a believer, as a priest, I don’t have any hesitation to say that the coming of the Gospel of Jesus Christ to the Americas is the best thing that has happened for us.

MITCHELL: We reflect, we remember, but let us let go. Let us heal and we need to move forward.

LAWTON: Leaders at the Tekakwitha conference say there doesn’t need to be a conflict between native ancestry and Catholicism. That’s something they try to teach to the next generation. Tasha Smith first came to the conference as a child.

SMITH: It was the first time as an eleven year old coming to me like ‘wow, these people know how to sing in their native language and they’re praying in their native language,’ and it was just an amazing experience.

LAWTON: Native American Catholics say the Church is doing a better job of celebrating diversity than it had in the past.

SANDS: Since Vatican II, you know, there’s a much greater openness to the expressions of cultures, inclusion of cultures in liturgies and in our life as Catholics.

LAWTON: Nature has always played a key role in native spirituality, and that’s true for Native American Catholics as well. They were greatly inspired by Pope Francis’ encyclical on the environment, especially his many assertions about the close ties between humans and the earth.

MITCHELL: I have met a number of people from other cultures who have said it was like reading something that a native person, first people of this land, would write. So now, native spirituality is taking deeper roots within the hearts of our Christian people.

LAWTON: Many Native Americans believe that’s one more example of how the Catholic Church is moving beyond the mistakes of the past.

I’m Kim Lawton reporting.