DEBORAH POTTER, correspondent: For Kelly Lange, it's another day of treatment at a clinic near Baltimore for the disease she's been fighting for 13 years.

KELLY LANGE: I have metastatic or Stage Four breast cancer, which is a terminal illness. If I don’t die of something else first, this disease will kill me.

POTTER: Cancer is Lange's biggest battle, but not her only one. She's also lobbying for a new law in Maryland that would allow doctors to prescribe lethal medications to people like her who are terminally ill so they can end their lives on their own terms.

LANGE: I’ve seen some people have a very peaceful end, where they are comfortable. And I’ve seen some people experience a lot of bloating, which can be mildly uncomfortable. But what worries me is I’ve seen some people in excruciating, uncontrollable pain. I really feel like if I had the option to avoid a week or three weeks of excruciating pain, it would be such a comfort to me as I progress in this disease—knowing that I had a little bit of control over something that is otherwise uncontrollable.

LANGE: I’ve seen some people have a very peaceful end, where they are comfortable. And I’ve seen some people experience a lot of bloating, which can be mildly uncomfortable. But what worries me is I’ve seen some people in excruciating, uncontrollable pain. I really feel like if I had the option to avoid a week or three weeks of excruciating pain, it would be such a comfort to me as I progress in this disease—knowing that I had a little bit of control over something that is otherwise uncontrollable.

POTTER: Maryland is one of 23 states where so-called "death with dignity" bills were introduced in 2015. Supporters believe they're gaining momentum now that California has become the fifth and largest state to allow physicians to aid in dying. The proposed laws would mirror what's been legal in Oregon for almost 20 years. More than 1300 people there have used the law to get a prescription to end their lives; two-thirds of them have taken it.

Existing laws or pending legislation: New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, Montana, Washington

Legislation introduced in 2015: Missouri. Washington, DC, Massachusetts, California, Iowa, Wyoming, Connecticut, Colorado, Kansas, Hawaii, Oklahoma, Maryland, Alaska, Wisconsin, Rhode Island, New York, Utah, Nevada, Minnesota, Tennessee, Maine, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Delaware

One was Cody Curtis, featured in the award-winning documentary "How to Die in Oregon." She was of sound mind, had terminal liver cancer and 6 months or less to live. In 2009, she took a lethal dose of a sedative…

Cody Curtis (in documentary): “Yeah, I'm ready.”

POTTER: … and died at home, surrounded by her family.

Many doctors are not ready to see what they call "physician-assisted suicide" legalized in more states.

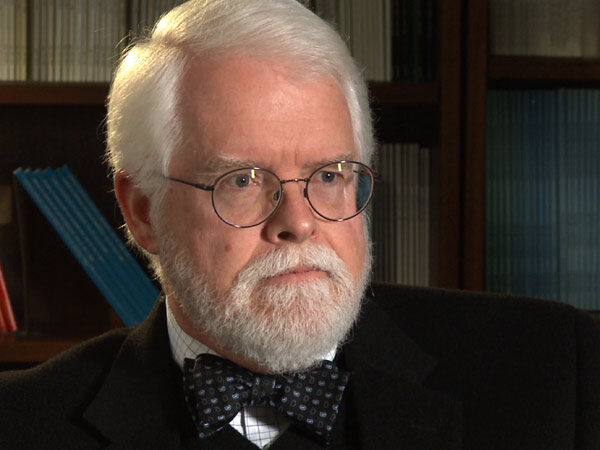

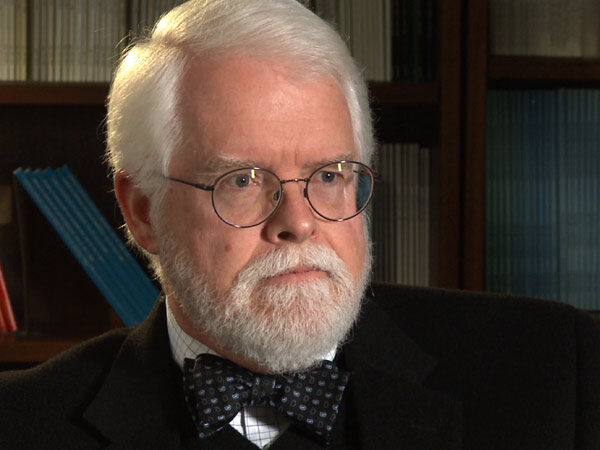

DR. G. KEVIN DONOVAN (Bioethicist, Georgetown University Medical Center): I think that it is a huge problem for patients and for doctors, if we introduce into the relationship that we no longer will focus on curing their illness; we will no longer focus on managing their symptoms; we will no longer focus merely on palliation of pain and other problems near the end of life, but we will also—in an almost bait-and-switch—say well if this stuff doesn’t work we’re going to make sure you die.

DR. G. KEVIN DONOVAN (Bioethicist, Georgetown University Medical Center): I think that it is a huge problem for patients and for doctors, if we introduce into the relationship that we no longer will focus on curing their illness; we will no longer focus on managing their symptoms; we will no longer focus merely on palliation of pain and other problems near the end of life, but we will also—in an almost bait-and-switch—say well if this stuff doesn’t work we’re going to make sure you die.

POTTER: Public opinion on the issue is shifting, and philosophy professor Sam Kerstein says it may have to do with baby boomers watching their aging parents die and facing their own mortality.

PROFESSOR SAMUEL KERSTEIN (Philosophy Department, University of Maryland): I think that people in this generation have had a lot of control over their own lives. They've had a lot of choices that they were able to make, living in relatively good financial circumstances, for example, and that maybe they want choices to have at the end. They want to control how they go out.

POTTER: More than two-thirds of Americans say doctors should be legally allowed to assist the terminally ill to end their own lives, according to a recent Gallup poll. That's up sharply from just two years ago, when about half of Americans approved. Why the change? One woman's story may be partly responsible.

Brittany Maynard was 29 when she learned she had terminal brain cancer. She moved to Oregon so she could get a prescription to end her own life, and she became an advocate for the "death with dignity" movement, with videos on YouTube getting millions of views.

BRITTANY MAYNARD: I chose this for myself. I would never sit here and tell anyone else that they should choose it for them. But my question is who thinks they can sit there and tell me that I don't deserve this choice?

DONOVAN: If the patient wants to commit suicide, that is not illegal in any of the 50 states, so the legislation isn’t needed for that. What the legislation does is include physicians in that patient’s suicide, and gives legal protections not to the patients, but to the physicians.

POTTER: Almost all religious groups oppose aid in dying. The Catholic Church is particularly outspoken.

REV. THOMAS PETRI (Academic Dean, Dominican House of Studies): The church's viewpoint on assisted suicide and euthanasia is that it’s never permissible to take a life, an innocent life, for the sake of alleviating suffering; that essentially you are killing a person to remove suffering from their lives.

REV. THOMAS PETRI (Academic Dean, Dominican House of Studies): The church's viewpoint on assisted suicide and euthanasia is that it’s never permissible to take a life, an innocent life, for the sake of alleviating suffering; that essentially you are killing a person to remove suffering from their lives.

POTTER: Father Thomas Petri is academic dean of the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, DC. He fears that new laws will let doctors pressure patients to end their lives.

PETRI: My bigger fear is that it’s going to become very easy for patients themselves to feel morally pressured to do this—to see themselves in those last stages of life as useless, as a burden to their family, as a burden to their loved ones, as a burden to the world, when as a man of faith I have to say, on the contrary, it’s the sick who show us what it means to suffer well, to suffer beautifully, and who give us the opportunity to care for them as we would care for a suffering Jesus Christ.

POTTER: One of the few religious faiths to officially support aid in dying is the Unitarian Universalist Church, where Alexa Fraser is a seminarian. For her, the issue is personal.

ALEXA FRASER: My dad was a total character—very, very independent, and as part of his independence he knew how he wanted to die. Or at least he knew how he didn’t want the last of his days to go.

POTTER: Alex Fraser had Parkinson’s disease. At the age of 90, he tried to kill himself twice before succeeding with a gun. His daughter and her husband found him.

FRASER: It was horrible. Nobody should have to go through that, least of all the person who’s dying.

POTTER: Fraser is now an outspoken advocate for the "death with dignity" bill in Maryland.

FRASER: My personal theology is really very simple: It’s about kindness. Surely we can be kind to one another. I see nothing kind about somebody being at the end of their life, not getting the choice that they want to make, and in pain and suffering. Don’t tell me it’s about doctors and pain and palliative care solving every problem. It doesn’t.

POTTER: Both sides in the debate say what they want is "death with dignity," but they don't mean the same thing.

KERSTEIN: There’s a sense in which people are said to lose dignity near the end when they can’t take care of themselves. They can’t dress themselves, can’t feed themselves, and so forth. Now on the other side, people also appeal to dignity but they appeal to a different notion of dignity. For example, a notion that persons have a special worth, no matter what happens in their bodies, no matter what control they lose. And on this idea we might be disrespecting the dignity of persons in helping them die sooner than they otherwise would.

KERSTEIN: There’s a sense in which people are said to lose dignity near the end when they can’t take care of themselves. They can’t dress themselves, can’t feed themselves, and so forth. Now on the other side, people also appeal to dignity but they appeal to a different notion of dignity. For example, a notion that persons have a special worth, no matter what happens in their bodies, no matter what control they lose. And on this idea we might be disrespecting the dignity of persons in helping them die sooner than they otherwise would.

LANGE: There’s not much dignified about cancer, and things often get very messy, in every sense of the word, at the end. Perhaps this option would bring me some dignity, but I think for me it’s mostly being able to say, “I’ve had enough. This is it. I’ve had enough. I’m ready.”

Nurse: “One two, three—deep breath.”

POTTER: Would Kelly Lange be ready to actually take a toxic dose of medication to end her life? She says she's not sure. And for the time being, asking a doctor to write her a lethal prescription remains against the law in Maryland.

For Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, I'm Deborah Potter in Baltimore, Maryland.

LANGE: I’ve seen some people have a very peaceful end, where they are comfortable. And I’ve seen some people experience a lot of bloating, which can be mildly uncomfortable. But what worries me is I’ve seen some people in excruciating, uncontrollable pain. I really feel like if I had the option to avoid a week or three weeks of excruciating pain, it would be such a comfort to me as I progress in this disease—knowing that I had a little bit of control over something that is otherwise uncontrollable.

LANGE: I’ve seen some people have a very peaceful end, where they are comfortable. And I’ve seen some people experience a lot of bloating, which can be mildly uncomfortable. But what worries me is I’ve seen some people in excruciating, uncontrollable pain. I really feel like if I had the option to avoid a week or three weeks of excruciating pain, it would be such a comfort to me as I progress in this disease—knowing that I had a little bit of control over something that is otherwise uncontrollable.