BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: In the ongoing national debate about the morality of torture, the question is whether it is ever the lesser evil. We want to identify the underlying principles in the debate, beginning with part of President Obama’s reply at his news conference last Wednesday (April 29) when he was asked whether he thought the Bush administration had sanctioned torture.

President BARACK OBAMA (at White House news conference): What I’ve said, and I will repeat, is that waterboarding violates our ideals and our values. I do believe that it is torture. You start taking short cuts and over time that corrodes what’s best in a people. It corrodes the character of a country.

ABERNETHY: But can torture sometimes be justified?

Jean Bethke Elshtain is a professor of social and political ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School and at Georgetown University. She joins us from Nashville. Shaun Casey is a professor of Christian ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington. Welcome to you both. Shaun — never?

Dr. SHAUN CASEY (Professor of Christian Ethics, Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, DC): I think the bulk of the Christian moral tradition says that torture is never morally permissible. If you go to Christian Scripture, you go to the wide arc of Christian social teachings, you get a very consistent historical answer that it is never right to torture another human being.

ABERNETHY: What’s the underlying reason for this?

Dr. CASEY: Well, you look at basic Scripture, you look at Jesus in the Gospels about love your neighbor as yourself, do not repay evil for evil, love your enemy—so there’s this sense that each person is created by God in the image of God and has an inherent dignity, and torture would render that dignity undermined.

ABERNETHY: And Jean, what are the underlying principles for you?

Dr. JEAN BETHKE ELSHTAIN (Professor of Social and Political Ethics, University of Chicago Divinity School and Georgetown University): Well, the underlying principle for me is what I would call an “ethic of responsibility.” That’s an ethic that is especially important when we’re talking about statesmen and stateswomen who often have the lives of thousands in their hands, quite literally.

ABERNETHY: So they have a different rule, a different ethic, a different moral standard than somebody would if he’s just acting as an individual?

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Not entirely different. We don’t want a huge chasm to emerge. But I would say that there are extraordinary circumstances when harrowing judgments must be made by those we tax with the responsibility of keeping us safe, and at those times there may be a “lesser evil” kind of calculation to be made.

Dr. CASEY: We have about a 60-year tradition of international law and domestic law that regulates the behavior of those who, in fact, are called to be our political leaders and there is a consistent prohibition of the use of torture. In fact, the United States has been a leading catalyst in that international movement, so I agree with that. But I think we have some rules that are in place that prohibit torture.

ABERNETHY: But beyond what’s legal is what’s moral. I mean, they’re not always the same, are they?

Dr. CASEY: That's true, and as the president said the other night in part of the clip that you played for us, that he believes that a leader in his position who faces those harrowing decisions ultimately is going to decide on both, of the angels and on responsibility if in fact we as a country refrain from using torture.

ABERNETHY: So, Jean, the president then has this primary moral responsibility, would you say, of protecting the people?

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Yes, that’s why we have states. That’s the reason that people made the deal back in the 17th century to organize the state — to prevent capricious power and the slaughter of human beings willy-nilly. That’s the reason we have states and have leaders to protect us.

ABERNETHY: And do you think people generally, American people, expect that a president will, somebody has written, have, you know, has to have dirty hands?

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Well, the problem of dirty hands is a perennial problem in politics. What it means is that one can’t remain absolutely morally pure, that you take actions. You don’t know what the full ramifications of those actions may be. Now I fully agree, by the way, that torture is something that should be ruled out as a general norm. My concern is with certain very specific and tragic circumstances, if there are severe forms of interrogation that may well fall short of torture as we usually understand it but are certainly severe — whether those are permissible.

ABERNETHY: And Shaun, the classic argument for permitting an exception, an extraordinary circumstance is the ticking bomb scenario, you know, that somebody in your custody has information about when a terrible, terrible thing might happen that would cost the lives of thousands of innocent people. Under such circumstances, perhaps others, don’t the people in authority have the responsibility to do something extraordinary if they think that can give them information quickly?

Dr. CASEY: Well, the fist thing we should observe is that there are no historical examples of that being lived out in reality. That’s a hypothetical contrary to fact, that it never obtained in the real world. What I worry about is the lack of rules to govern that exception. Many people argue that because they can create a hypothetical case like this there should be no rules against torture, and I think that is a grave moral error. The problem is we never know if that information can be elicited by other means. There’s no way to verify that, indeed, torture is the only option in those cases. So what happens if you torture that person and you turn out to be wrong, the information proves not to be true? But what do you say then to the person who’s tortured at your hands?

ABERNETHY: Jean, you want to comment on that?

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Yes. I would say that the resort to extreme techniques would be used only after all other possibilities had been exhausted. It wouldn’t be the first resort; it would be the last resort, and again we’d have to be clear about what we’re considering torture here, because some of the most severe forms I think must be ruled out. But there are other forms of enhanced interrogation that, I think, under those extreme circumstances and as an exception, may well, under the ticking time bomb scenario, be resorted to.

ABERNETHY: There is a recent poll by the Pew Research Center that found that 71 percent of Americans — American adults — said torture can be justified often or sometimes or rarely. Only 25 percent said never. Is that influential to you at all?

Dr. CASEY: I think that shows the influence of the Rupert Murdoch school of ethics — that we’ve been watching Jack Bauer, where torture is routinely shown to be effective on our television screens. I don’t think we decide what is moral and what is immoral based on the latest Pew poll about American opinion.

ABERNETHY: Jean, and what do you think of investigation and perhaps prosecution of those who authorized what was done?

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Well, it strikes me that, number one, it would immediately be politicized in a way that would be egregious and unacceptable, and number two, there’d be the question of how far back you go. Extraordinary rendition began under President Clinton, for example. So I think that that kind of going back and second-guessing those who in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 were dealing with shock and horror and fear about another imminent attack and were asked by CIA operatives in the field whether certain things were permissible—it strikes me that the best thing for now is to go on and to make clearer what we expect from those who are interrogating even high-value targets and operatives of Al Qaeda, for example.

ABERNETHY: Shaun — investigation, prosecution?

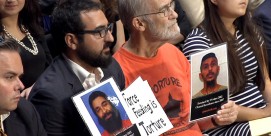

Dr. CASEY: We need a thorough moral accounting of what’s gone on. We’ve had an air of moral permissiveness in the last administration under which tens of thousands of innocent people have been tortured — not simply the special Al Qaeda cases. We need to find out why that happened. We need to find out who was accountable in order to build a very tall wall against this kind of behavior. We need to empower the folks who do the interrogating with very bright lines about what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable. At this point that, in fact, is not clear.

ABERNETHY: But, quickly, would you come out saying that there could be sometimes an exception to the “never” position?

Dr. CASEY: No.

ABERNETHY: No. Never?

Dr. CASEY: Never.

ABERNETHY: Thanks to Shaun Casey and Jean Bethke Elshtain.

Dr. ELSHTAIN: Thank you.