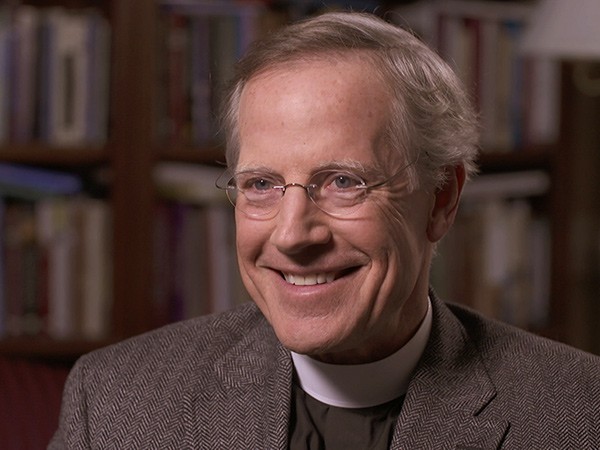

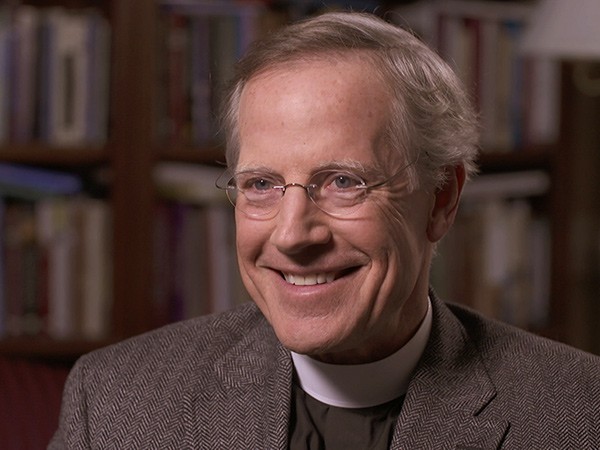

KATE OLSON, correspondent: As a Sunday of worship winds down at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, what’s known here as the evening community gathers for the Celtic evensong and communion service. This contemplative offering has become the most popular of seven services over a weekend, drawing hundreds of people. St. Stephen’s’ rector is Gary Jones.

KATE OLSON, correspondent: As a Sunday of worship winds down at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, what’s known here as the evening community gathers for the Celtic evensong and communion service. This contemplative offering has become the most popular of seven services over a weekend, drawing hundreds of people. St. Stephen’s’ rector is Gary Jones.

REV GARY JONES: God is very much active and present in people from all sorts of walks of life and tradition, and if they find a way to open themselves up to that reality by participating with us, then we’ve accomplished what we set out to do.

Singing: “Christ before us, Christ behind us …”

OLSON: Jones created a liturgy drawn from ancient Christian worship centered on a personal encounter with the divine.

JONES: The aim very simply is to assist in drawing people deeper into their experience with God, who is already with them. We aren’t giving them God, somehow, but to help to open them up to an awareness, a deeper awareness of God’s love for them, God’s forgiveness, the hope that God offers, and God’s just essential presence.

JONES: The aim very simply is to assist in drawing people deeper into their experience with God, who is already with them. We aren’t giving them God, somehow, but to help to open them up to an awareness, a deeper awareness of God’s love for them, God’s forgiveness, the hope that God offers, and God’s just essential presence.

OLSON: There are periods of meditation throughout the service, with the liturgical team joining the congregation in silent prayer as the service begins.

JONES: What we discovered was people started coming earlier and earlier to church, because they saw this was a place full of prayer, and they wanted to be still.

Parishioner: ‘”Sometimes in the face of small alienations of life, I find myself hiding on my class room orange carpet again … “

OLSON: Rather than a sermon, people share their personal experience of the divine.

OLSON: Rather than a sermon, people share their personal experience of the divine.

Parishioner: “Even as he faced the reality that he didn’t quite fit the mold, I wonder if Jesus felt like me, a bit of a weirdo, an odd ball…”

OLSON: And Holy Communion is open to all.

“This is the table not of the church, but of the Lord.”

JONES: We tell the congregation every Sunday that it doesn’t matter to us who you are, where you come from, what spiritual tradition—or if you don’t have any. We believe this is God’s invitation to you, to all of you, to know the very near presence of God within yourself, within everyone around you and in our fellowship together.

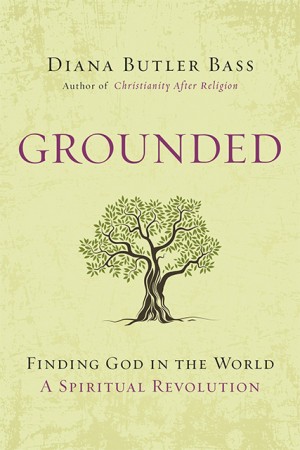

OLSON: For church historian Diana Butler Bass, the worship experience at St. Stephen’s is responding to what she sees as a profound change in people’s understanding of God.

DIANA BUTLER BASS: For much of the last millennium across Western Christianity, we’ve understood God primarily as being “up,” and yet that vision of God is the very vision of God that is now being questioned and in many cases rejected. And what is happening, if people still choose to believe in God, which most Americans do, they are developing new understandings of who that God is, and God has moved from “up there” to all around.

DIANA BUTLER BASS: For much of the last millennium across Western Christianity, we’ve understood God primarily as being “up,” and yet that vision of God is the very vision of God that is now being questioned and in many cases rejected. And what is happening, if people still choose to believe in God, which most Americans do, they are developing new understandings of who that God is, and God has moved from “up there” to all around.

OLSON: Having studied churches for the past two decades, Bass explores this new understanding with faith communities across the country.

BASS: The idea that God is really truly with us and that we’re not just sending our prayers up some elevator shaft to some far off place in heaven …

OLSON: Bass says this theological shift is at the heart of a revolution in which thousands of people are going through a spiritual transformation.

OLSON: Bass says this theological shift is at the heart of a revolution in which thousands of people are going through a spiritual transformation.

BASS: People don’t just want to receive truth from an institution. They want to participate with a tradition and make a truth that is meaningful for their own lives.

OLSON: Bass considers herself part of this revolution. A Christian, she says an exclusivist sermon drove her out of the church to find God in the world, including along the banks of the Potomac River.

BASS: It was literally a matter of putting myself into the world, opening myself to hearing the world around me speak, and then seeing with wider eyes than I had ever seen before. That’s really mysticism. And it’s not just available to someone who is technically trained in practices of deep contemplation. I’m a mom who’s a writer who lives in Virginia, and I’m a mystic.

OLSON: Finding God in nature and the world is a hallmark of mystics from many traditions throughout history. Today, a leading poll shows that one in two Americans say they have had a mystical experience, a moment of religious or spiritual awakening that has transformed their lives.

OLSON: Finding God in nature and the world is a hallmark of mystics from many traditions throughout history. Today, a leading poll shows that one in two Americans say they have had a mystical experience, a moment of religious or spiritual awakening that has transformed their lives.

BASS: That statistic has doubled in my lifetime, and statistics don’t do things like that.

OLSON: For Michael Sweeney, who leads family ministry at St. Stephen’s, a mystical experience while camping opened his eyes to see the connections between the holy and the natural world.

MICHAEL SWEENEY: When I look at scripture and Moses and the burning bush, Jesus in the wilderness, certainly there are examples in our tradition where the Holy manifests in nature. But it didn’t feel like that connection was made clear in the church of my upbringing. And so it took me hitting the road with my backpack and my tent and seeing Glacier National Park and Sequoia National Park, sleeping under those trees to start to make that connection and realize that it has been there all along.

MICHAEL SWEENEY: When I look at scripture and Moses and the burning bush, Jesus in the wilderness, certainly there are examples in our tradition where the Holy manifests in nature. But it didn’t feel like that connection was made clear in the church of my upbringing. And so it took me hitting the road with my backpack and my tent and seeing Glacier National Park and Sequoia National Park, sleeping under those trees to start to make that connection and realize that it has been there all along.

OLSON: Attorney Millie Cain grew up in the Episcopal Church but explored other paths, including Buddhist meditation and yoga.

MILLIE CAIN: It wasn’t that there was a failure on the part of the church at all. It was just that I was hungry for a more visceral experience of the divine. And it’s such a gift to experience that together in community, that awakening of the God within.

OLSON: Being part of a worshipping community reconnects us with this experience of holiness, Jones says, healing our sense of separation and loneliness.

JONES: So we hope that you would leave with this deeper feeling of connectedness to people you don’t know yet even, and a deeper sense of compassion, wanting to care for people to whom you’re connected so intimately.

JONES: So we hope that you would leave with this deeper feeling of connectedness to people you don’t know yet even, and a deeper sense of compassion, wanting to care for people to whom you’re connected so intimately.

OLSON: The weekend of worship closes with compline, a candle-lit service based on the monastic practice of ending the day together in prayer.

JONES: It’s an ancient experience that human beings have had for a long, long time, and if the church can help to awaken that, draw us deeper into it, it leads to a whole other way of life.

OLSON: For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Kate Olson in Richmond, Virginia.

Congregation: Amen.

KATE OLSON, correspondent: As a Sunday of worship winds down at

KATE OLSON, correspondent: As a Sunday of worship winds down at  JONES: The aim very simply is to assist in drawing people deeper into their experience with God, who is already with them. We aren’t giving them God, somehow, but to help to open them up to an awareness, a deeper awareness of God’s love for them, God’s forgiveness, the hope that God offers, and God’s just essential presence.

JONES: The aim very simply is to assist in drawing people deeper into their experience with God, who is already with them. We aren’t giving them God, somehow, but to help to open them up to an awareness, a deeper awareness of God’s love for them, God’s forgiveness, the hope that God offers, and God’s just essential presence. OLSON: Rather than a sermon, people share their personal experience of the divine.

OLSON: Rather than a sermon, people share their personal experience of the divine. DIANA BUTLER BASS: For much of the last millennium across Western Christianity, we’ve understood God primarily as being “up,” and yet that vision of God is the very vision of God that is now being questioned and in many cases rejected. And what is happening, if people still choose to believe in God, which most Americans do, they are developing new understandings of who that God is, and God has moved from “up there” to all around.

DIANA BUTLER BASS: For much of the last millennium across Western Christianity, we’ve understood God primarily as being “up,” and yet that vision of God is the very vision of God that is now being questioned and in many cases rejected. And what is happening, if people still choose to believe in God, which most Americans do, they are developing new understandings of who that God is, and God has moved from “up there” to all around. OLSON: Bass says this theological shift is at the heart of a revolution in which thousands of people are going through a spiritual transformation.

OLSON: Bass says this theological shift is at the heart of a revolution in which thousands of people are going through a spiritual transformation. OLSON: Finding God in nature and the world is a hallmark of mystics from many traditions throughout history. Today,

OLSON: Finding God in nature and the world is a hallmark of mystics from many traditions throughout history. Today,  MICHAEL SWEENEY: When I look at scripture and Moses and the burning bush, Jesus in the wilderness, certainly there are examples in our tradition where the Holy manifests in nature. But it didn’t feel like that connection was made clear in the church of my upbringing. And so it took me hitting the road with my backpack and my tent and seeing Glacier National Park and Sequoia National Park, sleeping under those trees to start to make that connection and realize that it has been there all along.

MICHAEL SWEENEY: When I look at scripture and Moses and the burning bush, Jesus in the wilderness, certainly there are examples in our tradition where the Holy manifests in nature. But it didn’t feel like that connection was made clear in the church of my upbringing. And so it took me hitting the road with my backpack and my tent and seeing Glacier National Park and Sequoia National Park, sleeping under those trees to start to make that connection and realize that it has been there all along. JONES: So we hope that you would leave with this deeper feeling of connectedness to people you don’t know yet even, and a deeper sense of compassion, wanting to care for people to whom you’re connected so intimately.

JONES: So we hope that you would leave with this deeper feeling of connectedness to people you don’t know yet even, and a deeper sense of compassion, wanting to care for people to whom you’re connected so intimately.