Christopher Evans: Hillary Clinton’s Benediction

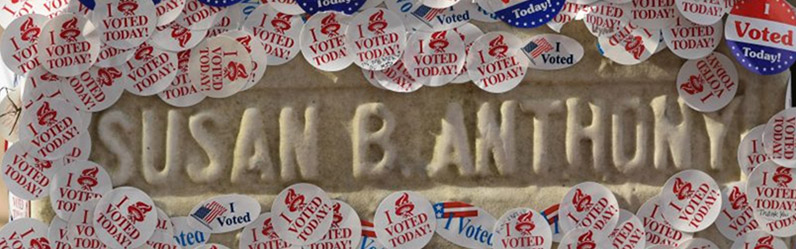

On Election Day, hundreds of people lined up to visit Susan B. Anthony’s grave in Rochester, New York. Their pilgrimage not only honored Anthony’s legacy as a women’s rights leader, but also anticipated that Hillary Clinton would be elected the first woman president of the United States.

Instead, the shocking victory of Donald Trump has left many Democrats and religious progressives trying to figure out how to respond to the election and the specter of a Trump presidency.

Historians like to point to moments in the past that parallel contemporary social-political realities, often reassuring people that in some way we’ve been there before. I join many Americans, however, not only in profound disappointment over the election results, but also unsure how people of faith, who care deeply about progressive politics, should engage a Trump presidency—especially in the wake of a wasteland of tweets, campaign speeches, and public statements laced with xenophobic, homophobic, racist, and misogynist utterances.

There is no doubt that Hillary Clinton carried a great deal of political baggage into her campaign, with many viewing her as a cold, calculating liar or as an establishment politician who echoed the strains of a “been there done that” liberalism. As she fades from the American political scene, the cottage industry of “Hillary bashing” will likely gain a new resiliency, especially from many who, I fear, will use her as a scapegoat for the Democratic Party’s election defeat. Yet many Clinton supporters and detractors often fail to recognize the role Clinton’s religious convictions played in her political career, and how the legacy of her faith might very well be her enduring contribution to the unsettled political landscape of our era.

Hillary Clinton was perhaps the most religiously grounded presidential candidate in the United States since Jimmy Carter. Throughout her career, Clinton has constantly spoken of her foundation in the Methodist faith of her childhood, reflecting upon her roots in the theology of John Wesley and the social teachings of Methodism. In a 1996 address to the General Conference of the United Methodist Church, Clinton articulated how her faith formed her vision of public service: “In the name of Jesus Christ, we are called to work within our diversity, while exercising patience and forbearance with one another. That call to humility and forbearance and patience is not only important for the work of the church within the church, but it’s crucial to our work outside. It calls us to try time and again to reach into the lives of those who are left out.”

In many ways Clinton’s humility, forbearance, and patience were consistently on display during the fall campaign, in which she was the repeated target of her opponent’s bellicose and misogynous attacks. Consider Trump’s physical intimidation of Clinton during the presidential debates, his stream-of-thought tweeted insults, and the frenzied rhetoric of his many supporters who spoke of Clinton as a near-satanic figure who needed to be locked away. Despite these attacks, Clinton showed a grace and class that few male candidates running for president over the last several decades have exhibited.

At times in her public life, Clinton did put her personal and political flaws on display, coming across as cold, stubborn, and angry. In many ways, she suffered the fate of Susan B. Anthony and other women in American history whose efforts to raise the bar of social equality earned them the label of being “unnatural.” Like Anthony before her, Clinton’s greatest sin was she was guilty of acting like a man. I understand the importance of calling for national unity in the aftermath of a contentious election, and it’s a sign of Clinton’s respect for the American political system that she was able to be gracious in defeat. But there is absolutely nothing in Trump’s record to indicate he is able, or willing, to engage the deep political divide in American society that I fear will only grow wider during a Trump presidency.

In her concession speech, Clinton concluded with a reference to the Apostle Paul’s words from the Book of Galatians: “Let us not grow weary of doing good, for in due season, we shall reap if we do not lose heart.” These words serve as an appropriate benediction to Hillary Clinton’s political career, as well as a challenge to religious progressives to find ways to move ahead in the face of what has now become for many Americans not just an unsettled, but a terrifying political landscape.

People will continue to debate the merits of Clinton’s candidacy, and my guess is that she will never escape the shroud of suspicion and outright hatred that has followed her throughout her public life. I hope, however, that many will receive her words from Galatians not as a eulogy for a failed candidacy, but as a much needed blessing that gives to those today who are angry, depressed, and fearful the faith to engage an uncertain future in confidence, perseverance, and, most of all, hope.

Christopher Evans is professor of the history of Christianity at Boston University. He is the author of several books, including Liberalism without Illusions: Renewing an American Christian Tradition and Histories of American Christianity: An Introduction (both published by Baylor University Press). His latest book, The Social Gospel in American Religion, will be published by New York University Press in the spring of 2017.