In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

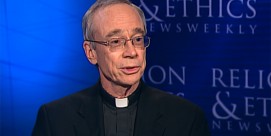

Reverend Eric Dudley

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview with the Reverend Eric Dudley, rector of St. Peter’s Anglican Church in Tallahassee, Florida:

Q: How did your parish come to be associated with the Anglican Church of Uganda?

Rev. Eric Dudley |

A: As we struggled through all of the issues in the Episcopal Church, in trying to discern what God was calling us to do, I did some of that struggling alone, or with fellow priests. I had some wonderful priests on the staff and went back and forth and back and forth in heart and mind trying to figure out what I could do, and at one point I had decided that I would just go back to South Carolina, which is where I’m from. But I had a dear woman who visited me in my office one day, and she said, I don’t know what you’re thinking about doing with this whole Episcopal mess, but if you should choose to leave and go back home, she said, what probably is going to happen here is we’re all going to go to different places. We’ll have people that go to Catholic churches or Baptists churches or whatever, and we’ll lose this community we have, and I hope that you won’t do that. And then along the way I had other parishioners here and there dropping that hint: I hope that we will create some strong Anglican presence here, and we won’t just give up on having Anglican worship in Tallahassee that’s faithful. So I kept struggling with that as a possibility, and then I had this fellow who had served on vestry who came to me late in my decision-making process, and he said to me, I don’t know where you are in the struggle, but I want you to know this. If you should decide that you’re going to create an Anglican church, I’ve got a building for you. And I said you’re kidding. What are you talking about? And this is a fellow who is a builder and commercial developer here in town, and he had been out at his barbecue grill one night with the next-door neighbor, who had bought this [United] Church of Christ that was defunct and was about to turn it into office buildings and was asking him to go in with him in this deal, and he said he got in bed that night and all he could think was Anglican church. So he got up the next morning and came to my office and said I just want to put this out there. So I went home to my wife who knew where I was in all these struggles, and I said okay, now I just had a building dropped in my lap. So that sort of was the end of the deal for me. Instead of going back to South Carolina and creating an Anglican church there, which I had considered doing, I decided maybe it was best that I just stay here. And so I left St. John’s, where I’d been rector for 10 years, and I left happily. I loved it, it was a wonderful church for 10 years, but on my last day I preached a sermon just reminiscing about all the wonderful times we’d shared together, and then at the peace I said a farewell. I told them they knew this had been a long and hard struggle for me, and that my family and I couldn’t bear this struggle any longer, and that I wished them well. And I left, and then the very next week – well, one thing I did say, at that very last moment, I didn’t invite people to come join me, I didn’t try to raise a crowd, but what I said is I’m going to create an Anglican church here in town and I hope to begin worship next week, and I left, and my friend had gotten a dozen men together and bought this building from his friend and said it’s available for you to use however long you need it, and so the very next Sunday we worshipped here, and that’s sort of how it came about.

Q: How many people from the original church came with you, and how many people do you have now worshipping in your parish?

A: We average around 600 folks on a given Sunday. We had a little more than 800 show up for our first Sunday, which was astounding, because I’ve got to tell you I had no idea who might show up. I knew I’d be here, and I knew that my family would be here, and I knew of a handful of staff members and some vestry that would definitely be here, so I thought you know what, if we have 30, 35, 40 people we’re going to have church, and I was just blown away when I walked out that morning and came over here and there were, you know, we were bursting at the seams. There were people standing, people had to be outside, there wasn’t adequate space. So I would say that somewhere around 800 came from the previous parish. We averaged over there about 650 in worship, so we had a lot of regular worshippers over there and some who probably weren’t very regular worshippers over there who came here. That first day I’m sure we also had people who had no intention of being members of this church who just showed up to show support, who were part of other Episcopal churches who wanted to show support. So we started with somewhere around 800 members, and we’ve grown. Now we’re a little over 1200 members, but really about 600 people who are in worship. Of course you don’t have the same 600 every week. It fluxuates, but 600 is what we average.

Q: Why did you feel you could no longer be a part of the Episcopal Church?

A. That was a long and difficult struggle for me. I had been happy as an Episcopal priest for many years, served 10 years as rector of St. John’s, loved the people, loved the church, and I could be okay for a long time with having a renegade priest or bishop here or there taking odd positions on things, you know, some bishop who said he didn’t believe in the Virgin Birth, some priest over here who said it wasn’t necessary to believe that Jesus was historically, physically raised from the dead, some other priest over here presiding at same-sex unions. But then when it came to the point that it was the church’s official position, that the church officially was endorsing some of these beliefs, then it was a very different issue for me, because that church is what I’m representing. I’m under the umbrella of the Episcopal Church. I’m a priest at that church, and can I in good conscience continue to bring people, innocent people who are seeking to know and love the Lord, into such a church? And that became really apparent for me one particular day when I had a young man who came to visit my office. He was kind of a good old Southern boy, brought up down South, and had never been in a church his whole life. His family was unchurched, and then he started dating a girl who came to our church. She was a Florida State student, and they started dating, and she started pulling him into church, and he started attending some classes, and he began to really believe all this business about Jesus and resurrection and scripture and sin and redemption, and he wanted to talk to a priest, so he came, and he sat in my office, and we had the most wonderful conversation, and there was a real earnest seeking-for-faith in this fellow, and when he left my office that day instead of my feeling jubilant, joyous that this fellow was coming into the church, I felt depressed. I thought, you know, is this a good thing? Am I guiding him in the wrong way? Have I brought him into a church that is going to mislead him? Does he think he’s getting into something that’s very different from what he’s really getting into? And then I had to really struggle with whether I could really keep doing catechumen classes and continue drawing people into the life of a church that is obviously going in a very different direction than I felt I could go, and that really began the move for me. I had a bishop friend who sat down with me at one point and pled with me to reconsider. Please don’t leave the church, stay in the church, we need you to stay in the church, and I said can you tell me any strongly orthodox priest or bishop who feels that we could win the battle? That it’s worth staying here and fighting this fight for the sake of this church? And he got tears in his eyes, and he said no, I don’t know anybody who thinks that this battle can be won. And I said then tell me why I should stay. And he said because there’s still a possibility. Not for your children, or your grandchildren, but maybe for your great-grandchildren. If you can hang in there, then some day this church is going to come around. And I said, so you’re telling me that I should give the next 25 years of my ministry fighting battles in the hope that just maybe some day for my great-grandchildren there might be a shred of gospel orthodoxy left? I said there’s no way. I’d much rather pour my energies out into building some strong, new church that’s still faithful to Anglicanism but that’s strongly, unapologetically orthodox. A church where I don’t have to continually be fighting battles with things that I think should be givens. And so that was the issue for me. I didn’t change as a priest, that’s the thing. I was still believing and practicing the things I’d always believed and practiced. I hadn’t changed an iota in my theology. I was still practicing those things that priests 100 years ago were practicing. I felt that a church had moved away from me, not me away from the church, and not only away from me, but away from many priests and lay people who were earnestly seeking to be faithful to the gospel of Jesus. So that’s where it all started for me.

Q: A lot of churches coming to the same decision you did are still trying to hang on to their church buildings, and there are some protracted legal battles about who should stay on the property. Why did you decide not to go that route?

A: I personally could never go the legal route, and for me it’s not biblical. It’s not the thing to do. I think to drag the dirty laundry of the church out into the public arena and to have these horrible, protracted battles in secular courts over property is just the wrong thing. St. Paul warns us about it in Corinthians, but I can’t judge other priests who have made other decisions and maybe for reasons that I don’t understand. I do understand a priest who is in a church that is relatively new and a hundred percent of the congregation wants to leave the Episcopal Church, and it’s those same people who actually built that church, paid for it, and bought the land 25 years ago. I can understand that priest really, really thinking that it would be just that the Episcopal Church should allow them to take the property. I think it becomes more murky maybe with older buildings that have been around, and especially with churches that have divided memberships. In the church that I was serving, St. John’s, it was a divided membership. I had a large number of people, obviously, who shared my commitments, but there were still many others there who didn’t, and yes, we could have had a battle, and I think the majority of the parish, the majority of the participating parish, certainly, would have stood where I stood, and it would have been a long, bloody battle, but what do you win at the end of it? You win some bricks, but what have you done to the gospel, what have you done to the witness of the gospel in this community, and what have you done to relationships between people? Because long after that battle’s over, you’re still going to have serious hatred between people who have been members of the same parish, and so for me that’s not the way to go, and I had told people there, I had some folks who had visited with me some months before I made this decision, where I think they saw that in my soul I was struggling deeply. And they came to me and they said honestly we’re worried that you’re going to end up leaving and trying to take this church with you, and I said, well I can’t tell you that I won’t leave the Episcopal Church, because I may not be able to do this long term, but I promise you that I will never, ever try to take this building. And so when it came time for me to make that decision I knew I had to be true to that promise, so there was never for me a thought of entering into some legal battle. The thing, though, that was shocking to me was the number of people who had a long history in that parish. Their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents helped build the place, they were married there, baptized there, they have family members in the grave there, they have stained glass windows in the names of family members, and they chose to come, a number of them, and so really the sacrifice was much greater on the part of some of those laypeople, who had a long history in that particular church, than it was for me, because I had only 10 years of history in that church.

Q: Let’s talk about your affiliation with the Anglican Church of Uganda. For a lot of Americans that seems strange, that a group of US Episcopalians would now all of a sudden be a part of the church of Uganda. How does that work, and why did you want to affiliate with them?

A: Well, first I think it’s wonderfully ironic that you got a bunch of wealthy, white mostly, Americans who found their salvation, so to speak, in a bunch of poor Africans. I mean, you know God smiles at that. When I was preparing to leave, I clearly wanted to remain in the Anglican tradition. I care about being an Anglican priest, and I didn’t want to give up that heritage. I didn’t want to go off and do my own thing as one independent clergyman, and so did the associate priests who were with me, so obviously we had to be under the authority of some bishop somewhere, and we struggled with how to affiliate. What should we do? And one of the possibilities was the Anglican Mission of America, and I just had a great love and respect for the Anglican Mission, but at that time it was pretty hardnosed about the ordination of women, and that is not an issue for us, and we didn’t want to get pulled into all of that, and so that couldn’t be a possibility for us at that time. So I called my bishop, the bishop of Florida, who had retired and moved to Dallas, Texas, Steven Jecko, and I called Bishop Jecko in Texas, and I said here’s my quandary. I have come to this place where I can’t stay in the Episcopal Church. I’ve got to leave, but I’ve got to be under some bishop somewhere, and I need your help. Would you be willing to help me find a bishop? And he said yes, I will, I will find you a bishop. And so I put it in his hands, and I went on about my daily duties, and then three days before I announced to the congregation that I was leaving, I was beginning to sweat a bit, and he called me on the phone, and he said, I have put you under a bishop, and I said who? And he said, well, I’ve put you under the archbishop of Uganda, and he said I put you there because number one he’s willing, the ordination of women is not an issue for him, and he’s someone you already know. And he’s right. We already had relationships with Africans because of mission work we were doing in Africa, and so I said, well that’s awesome, we do have a relationship with many Africans, and that’s great that he’s willing to take us. So Bishop Orombi through Bishop Jecko had signed off on that. We sent all our paperwork to him, and we were immediately under his authority, so that’s how it worked. That’s how it came about to be Africa, and it’s been a remarkable thing, wonderful in many ways. We have 24 churches in north Florida who have been a part of the diocese of Florida, now Anglican churches that are a part of an Anglican alliance, and they’re priests that I’ve known for years and are sitting around the table, are having coffee and prayer with them for years, and here we are sitting around the table again together, and you look about and here’s this one priest who’s under Bolivia and this other priest who’s under Uganda and another under Kenya, and it’s just kind of neat to see the way that God’s church universal is sitting together right there at that same table.

Q: How important is that? You mentioned Anglican identity. Why is that so important to you?

A: Well, you know, it might seem odd, but I read too much Wesley along the way. I read too much of John Wesley, and I had a great love at the end of college and the beginning of seminary for John Wesley, for his evangelical zeal, but also for his catholic commitments, his commitment to the centrality of Eucharist, his commitment to common prayer, his commitment to order and discipline and structure, and that really appealed to me, and Wesley, you probably know, never intended to start a new church, Methodism, and when he died in 1791 he was still a faithful Anglican. So Anglicanism has for a long time meant much to me. I guess I don’t fit real well in the Free Church tradition that is very Protestant and focused only on scripture, and it separates itself from any sacramental notion of much of anything, but neither am I completely comfortable in a Catholic church that sometimes doesn’t give the kind of time and energy at all to scripture and that takes hold of some other beliefs that I struggle with that I think don’t have a scriptural foundation. So in Anglicanism I see the marriage of the two. I see the very best Protestantism and the very best Catholicism coming together in one, and for me it’s enormously appealing and faithful and rich, and I care about that, and I want my children to be nurtured in that kind of gospel, rich tradition, and so that’s why I’m an Anglican. I’m not willing to give that up. I don’t ever, ever want to give that up. I don’t want my children to have to give that up.

Q: Bishop John Guernsey is not being invited to the Lambeth Conference, just like Bishop Gene Robinson was not invited. What does that say to you?

A: I think you’re right, I think that Guernsey, my bishop, and a number of the bishops have not been invited to Lambeth, and you’re right, Gene Robinson has not been invited to Lambeth, but I think what that reflects is the reality of a broken Communion. It is broken. My archbishop, who obviously has been invited to Lambeth, Archbishop Orombi, has chosen not to go, and 300 other bishops in the Anglican Communion have chosen not to go. There may be more. At least those 300 who are part of the Southern Cone who were at GAFCON [Global Anglican Future Conference] in Jerusalem have chosen not to be part of Lambeth, and I think it simply reflects the reality that we’re dealing with of broken communion.

Q: What would you like to see happen at Lambeth to address the situation?

A: Well, there was a possibility early on that Lambeth might really get focused on creating a covenant that all Anglicans must give themselves to in order to be a part of this Anglican Communion, but in recent weeks it looks like that’s really not going to happen. And they’ve made clear that they’re not going to put forth any resolutions whatsoever, so at the end of the day it’s really not going to be much more than tea with the Queen, I’m afraid, but that seems to be the focus. It’s all about fellowship and not really much substance, so I don’t think there’s any hope that anything of any great magnitude is going to come out of Lambeth.

Q: You’ve articulated how you want to be part of that Anglican tradition, yet it seems like the structures of Anglicanism are struggling with how someone like you can still fit. Is that difficult for you?

A: No, because I don’t think the struggle is trying to figure out how somebody like me can fit in Anglicanism. I think the struggle is how Anglicanism can still hold onto people like the Episcopal Church. I’m a part of the larger majority of Anglicans. I mean, the overwhelming majority of Anglicans stand where I do on these issues, and we’re being true to classical Anglicanism. We haven’t changed in those commitments. It’s the same commitment. Go back and look through the last several hundred years of Anglicanism, and where we stand is where they stood. The changes come with the American church and the Canadian church, and they’re the ones who have stepped outside of Anglicanism, and I think that they’re the ones creating the division. So the possibility for the future in terms of having a united Anglicanism, that is an Anglicanism that includes all the people that heretofore have been included, will rely wholly in their hands, whether or not they choose to come back into the orthodox faith.

Q: What do you see happening structurally, though, to resolve the crisis?

A: Well, I think very sadly the American church over and again has been clear that it will not go back on its commitments. It’s made a commitment to the gay agenda. It sees it as a prophetic commitment, it sees itself as leading the rest of the church to what the future must be, a complete embrace of the gay and lesbian lifestyle, and that means the ordination of practicing homosexuals, the blessing of same sex unions, that all of that must be embraced. And they see that, many of these leaders, including the presiding bishop of the American church, sees that as a prophetic calling, and they’re not going to back up on that. That’s not going to change. And unfortunately because of that I don’t see any possibility of any union any time in the near future between the Episcopal Church in America and the larger body of Anglicanism. I think what you see happening as a result of GAFCON, the Global Anglican Future Conference that took place in Jerusalem with my bishops, is that they’re seeking to create a fellowship of confessing Anglicans, that is, those who want to be clear in their commitments to orthodox faith. And they’re going to have a council of bishops that moderate it, that fellowship, and I think that’s where it’s going to end up, that I’ll be part of an American Anglicanism that is under the fellowship of this global structure, and there will be other people, like the Episcopal Church in America, that seeks to be a part of some other branch of Anglicanism. That’s how I see it coming down, sadly, unfortunately. I sure wouldn’t want that. My hope would be that we could all stay together, but I think that I — It’s sort of like this: Several years ago I attended a meeting in Dallas, Texas, and the archbishop of Uganda was there, and being good Anglicans like we are, all the priests were very anxious about the archbishop of Canterbury, and so they kept raising their hands asking questions of the archbishop of Uganda, well, what about this with Canterbury, and what about that with Canterbury, and what about this with Canterbury, and the archbishop of Uganda said, my brothers and sisters, I have great love and respect for the archbishop of Canterbury, but the archbishop of Canterbury did not die on a cross to save me from my sin. And I think he’s right. At the end of the day it’s about gospel faithfulness, above and beyond all the rest.

Q: So does what happens at Lambeth ultimately make a difference? Does it matter?

A: I think what happened in Lambeth in 1998 is they all signed off, the majority, strong majority signed off on Resolution 110 which made clear that the Anglican Church believes that homosexuality is in conflict with scripture, and that the blessing of unions and the consecration and ordination of practicing homosexuals is not acceptable. And that still where we stand, to this day, officially, that is still the position that has been reaffirmed over and over by the Anglican Church. Now the thing about it is, this Lambeth has made it clear it’s not doing anything about any new resolutions. So if no new resolutions are coming forward, and this is still the resolution that stands, then officially that’s where we are as a body. So again I don’t think anything’s going to come of this Lambeth, because they’ve stated, the archbishop has stated, the presiding bishop has stated, that there will be no new resolutions.

Q: What is your message to those bishops who will be at Lambeth?

A: I guess my message to those bishops who are choosing to attend Lambeth would be if they have any hope whatsoever to have this Communion continue to move together as a united body, then they have to stand by Resolution 110 from the 1998 Lambeth Conference, and they have to call the American and the Canadian church to repentance. I think that would be the solution.

Q: What about your local parish? Are you on hold waiting for something to happen, or are you moving forward?

A: I don’t think we’re on hold at all. We haven’t been on hold from day one. This is an energetic, vigorous, vibrant parish that is strongly moving forward with the gospel of the Lord. These people care about Anglicanism, so many of them lifelong Anglicans and some of them African Anglicans and English Anglicans, not just American Anglicans. And they’re moving forward with the gospel. I told our folks our first week, I said don’t you dare go to blog sites. Don’t do it. Stay away from it. Don’t get pulled into all that mire of anger and political tension. Leave it behind us. We made a decision about that fight, and we left, and we’re moving forward with the gospel of Jesus, and for those that are still in that mire, let them have that fight. They have to make their decisions, but we’ve moved on, and we’re joyfully under the archbishop of Uganda, and we’re joyfully under Bishop Guernsey in Virginia, who is a wonderful man, and we’re just here to serve, and so no, we’ve moved beyond it, and at the end of the day yes, we care what happens to Anglicanism worldwide, but we’re not bogged down in the fight.