In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Madeleine L’Engle

BOB ABERNETHY (anchor): Now, a profile of a best-selling writer of fantasy and adventure long before J.K. Rowling created Harry Potter. She is Madeleine L’Engle, whose science fiction, beginning with A WRINKLE IN TIME, like the Harry Potter books, has been both widely read by young people and strongly criticized by some religious conservatives. I spoke with Madeleine L’Engle a year ago about Christianity, censorship, science, suffering, and love.

Madeleine L’Engle broke her hip last year, and that has slowed her down. But on this evening, as an Episcopal lay woman she was saying vespers with the nine Episcopal nuns at New York’s Community of the Holy Spirit. L’Engle prays and reads the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer every morning and evening. For many years, she did her writing at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, where she is still librarian and writer-in-residence. So does all that Christian practice make her a Christian writer?

MADELEINE L’ENGLE: No. I am a writer. That’s it. No adjectives. The first thing is writing. Christian is secondary.

ABERNETHY: At occasional workshops for other writers, Madeleine passes on her unsentimental, uncomplaining approach to life and her craft.

L’ENGLE: Basically one word: write. So who would like to be the first to read?

L’ENGLE: Basically one word: write. So who would like to be the first to read?

A young poet went to Colette and complained that he was unhappy. And she said, “Who asked you to be happy? Write.” And I think that is very good advice.

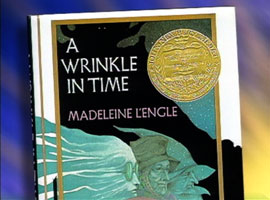

ABERNETHY: Madeleine is working now on a book about aging and an article about hate. She has written more than 50 books, of which the most famous is A WRINKLE IN TIME, published in 1961 after more than 30 rejections. The heroine is a teenager named Meg who expresses L’Engle’s own deepest belief.

L’ENGLE: Meg finally realizes that love is stronger than hate. Hate may seem to win for a while, but love is stronger than hate.

ABERNETHY: A WRINKLE IN TIME is a science-fiction fantasy that has sold more than six million copies and is now in its 66th printing. Readers still send Madeleine copies of that book and others to autograph, and she says she never tires of signing them.

L’ENGLE: Never, because anybody who has received as many rejection slips as I have is not going to complain about autographs.

ABERNETHY: Many Christians have found in Madeleine L’Engle’s books a profound religious message. Others have seen her witches and dark forces as essentially un-Christian, and their complaints to schools and libraries have made L’Engle one of the ten most banned writers in the country.

MS. L’ENGLE: We have always liked banning. And Hitler and his cohorts started banning books and then to killing people. You have got to be very careful of banning. What you ban is not going to hurt anybody, usually. But the act of banning is.

MS. L’ENGLE: We have always liked banning. And Hitler and his cohorts started banning books and then to killing people. You have got to be very careful of banning. What you ban is not going to hurt anybody, usually. But the act of banning is.

ABERNETHY: L’Engle’s view of the universe has been shaped by both Christianity and science. Often, at night, she reads both the Bible and books about particle physics, and she sees no conflict between them.

L’ENGLE: Religion and science? One and the same. I don’t have any trouble with it. A lot of people do. They have to put one here and one there, and I think they’re much more like that, each one informing the other.

ABERNETHY: But isn’t the skeptical scientific attitude a challenge to faith?

L’ENGLE: Religion is less accepting than science. Science knows things move and change, and religion doesn’t want that. So I am more comfortable with science. At the same time, I am not throwing God out the window.

ABERNETHY: But you’re making a distinction between religion and God.

L’ENGLE: Temple, the archbishop in the 19th century, said, “God is not chiefly interested in religion.” I like that.

ABERNETHY: L’Engle has experienced a lot of loss in her life: the death of her husband, Hugh Franklin, an actor well-known for his role as a doctor in the TV series ALL MY CHILDREN. She wrote about their marriage and his death in her book TWO-PART INVENTION. She wrote about her mother’s death in THE SUMMER OF THE GREAT GRANDMOTHER. Many of Madeleine’s close friends have died, and last Christmastime so did her son, Bion.

MS. L’ENGLE(reading from her journal): It’s late at night on Christmas Eve. We went to the Cathedral for the midnight mass. Bion died a week ago today. I still don’t believe it. Bion’s death has ripped the fabric of the universe.

MS. L’ENGLE(reading from her journal): It’s late at night on Christmas Eve. We went to the Cathedral for the midnight mass. Bion died a week ago today. I still don’t believe it. Bion’s death has ripped the fabric of the universe.

ABERNETHY: Madeleine has kept journals almost all her life, and she says writing in them about grief makes it easier to bear.

L’ENGLE: I am very grateful that I have a journal and that I can write, because that helps me to objectify things that might just mess me around emotionally otherwise. I can no longer look at this and weep and feel sorry for myself. I see it more clearly. And it sends me back to work.

ABERNETHY: Eventually, Madeleine says, she will write about her son. Madeleine sees suffering as a normal part of life, and she also says she feels closest to God when she suffers.

L’ENGLE: In times when we are not particularly suffering we do not have enough time for God. We are too busy with other things. And then the intense suffering comes, and we can’t be busy with other things. And then God comes into the equation: “Help.” And we should never be afraid of crying out, “Help.”

ABERNETHY: Madeleine also sees suffering as necessary for a full life.

L’ENGLE: Where there is no suffering nothing happens. One time, my godmother went to visit my mother, who was her best friend, and something awful had happened. I don’t know what. And she burst into tears, instead of offering comfort, and said, “I envy you. I envy you. You had a terrible life, but you have lived.”

ABERNETHY: L’Engle insists that, in the end, life and the universe are good. She remembers singing a sad ballad to one of her two granddaughters when she was a child.

ABERNETHY: L’Engle insists that, in the end, life and the universe are good. She remembers singing a sad ballad to one of her two granddaughters when she was a child.

L’ENGLE: And she said, “Gran, you know that is a bad one.” And I said, “What?” “Gran, you know that’s a bad one.” And I said, “Why, Charlotte? Because everybody dies?” And she said, “No, Gran. Nobody loved anybody.” And then it was the next night, putting them to bed, that Lena just looked at me cosmically and said, “Gran, is it all right?” She didn’t mean any thing … She meant the whole thing. “Is it all right?” And I swallowed my heart and my everything and said, “Yes, Lena. It’s all right.”

ABERNETHY: Madeleine grew up an only and, she says, a lonely child. So she loves family gatherings such as this one, with four generations. She says she expects to keep enjoying good company, good food, good talk, and work for another twenty years.

L’ENGLE: I was writing in my journal yesterday and ended a paragraph with, “I think it smells like hope.” And we have to hang on to that.