In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Mary Gordon

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: We have a profile today of Mary Gordon, novelist, essayist, and English professor at Barnard College in New York whose new book is called CIRCLING MY MOTHER. It’s a memoir of Gordon’s late mother and of the Catholic Church in which she was raised. Gordon is an outspoken critic of the church as an institution. At the same time, she remains strongly committed to her Catholic faith. Our reporter is Judy Valente.

JUDY VALENTE: Mary Gordon begins the day by walking her dog, Rhoda, in Riverside Park on Manhattan’s upper West Side.

MARY GORDON: I’m often thinking about what I’m going to write during the day because morning is a very reflective time for me. To look, to spend a long time looking, to get rid of your own narcissism, and to see what’s there rather than what you want to be there, I think, is a very important human exercise.

VALENTE: She’s been called a Catholic writer but says she considers herself a writer who happens to be Catholic.

Ms. GORDON: I have absolutely no desire to proselytize, nor do I believe that, you know, Catholicism will make people’s lives better. If you tell people you’re Catholic, they immediately take 50 IQ points off you, and so I think that because I am perceived by people as a Catholic novelist, there is a whole group of readers that think they don’t have to read me.

VALENTE: But millions have read her novels, short stories, and nonfiction works. Now she has written a memoir of her mother, a woman crippled by polio, a career woman whose later years were marred by alcoholism and dementia.

Ms. GORDON: The parent that you knew, the person that you knew, died, and then you have this sort of pathetic creature living a living death. And I wanted to get back past that, to recover a mother who was lively, gifted, difficult, and complicated, but not the pathetic creature that she was. And so I thought the way to get her back was to walk around her and think of all the different aspects of who she was — a mother, a friend, a worker, a person with a religious life.

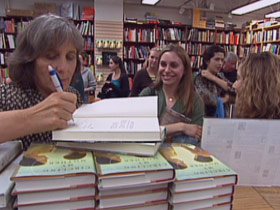

(speaking at bookstore): One of the most important aspects of my mother’s life was her Catholicism…

VALENTE: …and especially her friendships with priests.

Ms. GORDON (reading from CIRCLING MY MOTHER): It is almost impossible to convey to anyone under 50 the glamour, the shimmer, the esteem that attached to priests when my mother was young right through the time I was a teenager — in the mid-’60s, at least…

My mother and her friends, mostly unmarried, had very intense relations with priests who took them very seriously. Spiritually, they were their confessors, and that relationship enabled women to talk about their inner lives. I don’t think it was sexual. I think it was romantic.

My mother went on retreats with her girlfriends, and they would go away for a weekend. They would stay in convents, and they adored these priests. It was a connection with a man that wasn’t about keeping them in their place but was about taking them seriously and opening them up to a larger world.

VALENTE: Gordon says writing about the people she has loved, and lost, is a way of keeping them present.

Ms. GORDON: I really feel surrounded by my beloved dead, and there are some times where it’s almost literal, and particularly with my father, where I can say, “Hold my hand.” I believe that that love never ends, and if you loved and you were beloved, they’re with you.

VALENTE: Her characters are often haunted by guilt and doubt.

Ms. GORDON: Any thinking person has to come up against the anguish and the frustration of an ideal of love and a world in which horrible suffering exists, and to not be anguished by that contradiction, I think, is almost impossible for a thinking person. So, you know, just to say it’s God’s will and pretend that doesn’t hurt — that is using religion as a sort of anesthetic.

VALENTE: Her own Catholicism is constantly pulling her in different directions.

Ms. GORDON: Catholicism at its best creates a fullness of possibilities for being human that’s very, very dear to me, and people who are willing to die for it. At its best, it demands social justice, social commitment, a solidarity with the poor. It connects you to the whole world: rich, poor, educated, uneducated, people of all ethnicities, races. It is catholic, and I love that.

VALENTE: But when it comes to the institutional church dominated by men …

GORDON: You can’t feel comfortable. You’d have to be, again, an idiot to feel comfortable in Catholicism. I’m not comfortable, and I’m angry all the time.

VALENTE: Is that the type of thing that you say to the young women that came up to you last night, for example, after the reading?

Ms. GORDON: Yes, I do, and I think it’s true in all institutions unless women get in there and fight. It’s very hard. Men do not want women to take power alongside them. Historical patience combined with the good energy that anger can give you is the way, and I — that’s what I do tell the students. Don’t give up.

VALENTE: She sees a common thread between the religious instinct and artistic creativity.

Ms. GORDON: Writing and prayer both involve a lot of waiting, and I think that’s a very important discipline. The experience of prayer and the experience of creation are very similar, and there is this kind of, again, attentiveness mixed with an openness that is necessary for both the creation of art and for prayer.

VALENTE: Gordon has written what she calls prayers for the un-prayed for.

Ms. GORDON (reading prayer): For those whose work is invisible; for those who paint the undersides of boats; makers of ornamental drains on roofs too high to be seen; for cobblers who labor over inner soles; for seamstresses who stitch the wrong sides of lining; for scholars whose research leads to no obvious discovery. Grant them perseverance for the sake of your love, which is humble, invisible, and heedless of reward.

VALENTE: She believes there is in every human being a driving desire to tap into something that’s larger than one’s self.

Ms. GORDON: This desire for beauty and the desire for meaning are very mysterious, and for me they’re hints of something. They’re hints of a hunger for something that is not reachable except through something transcendent, some transcendent person. Why do we want meaning? It is ridiculous. Children suffer. Bad people do very well. There shouldn’t be a desire for meaning. Life should have told us that there is no meaning, and we keep searching for it, and we keep being angry when we don’t have it. So what is that hunger? What is that appetite? I don’t know. It’s very mysterious to me. But it seems to me an important way of understanding, or at least framing the question, what is it to be human?

VALENTE: Mary Gordon says it is hard to predict what the Catholic Church of the future will look like, but she believes it will no longer be the clergy-dominated church of her mother’s generation. She predicts the future church will consist more and more of small groups of believers who gather together, with or without clergy, for worship, community, and support.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Judy Valente in New York.