In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Watts Priest

BOB ABERNETHY (Anchor): We have a story today about a remarkable man in California. He is a Catholic priest from Ireland who has ministered for 37 years to both African Americans and Latinos in the Watts section of Los Angeles. Saul Gonzalez reports.

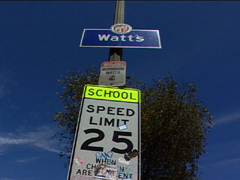

SAUL GONZALEZ (Contributing Correspondent): The Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts has long been synonymous with inner-city desperation and despair. It’s the neighborhood that exploded in urban unrest, after all, in 1965, and then again during LA’s 1992 riots.

Today, Watts is still home to some of the meanest streets in the city, but they’re streets walked regularly by Father Peter Banks, a Catholic priest who, dressed in his robes, rope belt, and straw hat, looks like a fish very much out of water.

Today, Watts is still home to some of the meanest streets in the city, but they’re streets walked regularly by Father Peter Banks, a Catholic priest who, dressed in his robes, rope belt, and straw hat, looks like a fish very much out of water.

Born and raised in rural Ireland, Banks arrived as a young priest in Watts in 1973, assigned to the Saint Lawrence of Brindisi Church.

FATHER PETER BANKS: My picture of America before I came was Hollywood, Disneyland, and the beach. So I got into the car, we drove up Century and we crossed Vermont, and I began to realize this is a very different world. It was all black, and the very first Sunday I stood up on the altar and I said what am I doing here? How will I ever understand the people? Will they understand me?

GONZALEZ: In the decades since, though, this Irish priest and the people of Watts have come to know each other very well, and Father Banks has become a beloved figure both in his church and the wider community. Father Banks says his taking an active role in the day-to-day life of the community has been key to being accepted by the residents of Watts.

(Speaking to Father Banks): How important is it for you to do what we are doing now, to get out and to walk the streets?

FATHER BANKS: Oh, I feel part of the flesh and blood and soul of Watts.

GONZALEZ: As he walks through the community, Banks meets and ministers to the casualties of drugs, poverty, and violence in Watts. One of them goes by the name “Red Man.”

GONZALEZ: As he walks through the community, Banks meets and ministers to the casualties of drugs, poverty, and violence in Watts. One of them goes by the name “Red Man.”

FATHER BANKS: Now, he never minds me saying this, but this man was shot thirteen times and survived.

RED MAN: I love this man. Really, he is the only white man who can walk Watts with no gun, just walking by faith, and walk here and know everybody. Everybody knows Father Peter. He is the true father of Watts. He is a real servant of God.

GONZALEZ: Red Man and a friend then ask Father Banks to lead them in an impromptu street corner prayer.

Central to the story of Watts and Father Banks’s church is the incredible demographic shift that has occurred in this community in recent years. Once synonymous with the African-American community, Watts is increasingly Latino. With that change has come tension.

FATHER BANKS: They call it the black and brown conflict. How do we get black and brown to come together?

GONZALEZ: That conflict sometimes expresses itself in violence, but often its face is a soft, unofficial form of segregation. Latinos largely stick to themselves, African Americans as well.

(Speaking to African American girl): You wouldn’t go out of your way to hang out with Hispanic kids?

AFRICAN-AMERICAN GIRL: Definitely no, I really wouldn’t because, I know it might sound racist, but if I see a Mexican girl or a Latino girl I’m just, like, not hanging out with her because she is just not my people. I know that’s wrong, but that’s just, like, the way it is in our society and our community.

GONZALEZ: It’s such feelings that Father Banks has tried to battle in Watts, making both African Americans and Latinos feel welcome in his congregation and breaking down walls of mutual suspicion and hostility. He’s done that by learning Spanish, slowly integrating some church services, and developing sensitivity to the problems of both Latinos and African Americans.

GONZALEZ: It’s such feelings that Father Banks has tried to battle in Watts, making both African Americans and Latinos feel welcome in his congregation and breaking down walls of mutual suspicion and hostility. He’s done that by learning Spanish, slowly integrating some church services, and developing sensitivity to the problems of both Latinos and African Americans.

GONZALEZ: Father Banks says being Irish can actually be an advantage in his work in Watts.

FATHER BANKS: I feel it is. One time I was talking to the black kids, that’s when I came first, and they were saying something about the whites, and I held up my arm and said, “Look at me,” and this little girl said to me, “Father Peter, you aren’t white, you’re Irish.”

I can relate very much to the black in the sense of the Irish being persecuted. It used to say in the States, I think, “No black or Irish need apply.” So I feel I do identify a lot with the African-American people and their pain and their suffering. I’m able to relate to the Latinos and say I am an immigrant, and I tell the Latino people, I say, I am an immigrant, too. I came here and, I said, I am far away from my own land. I know what you go through, too.

GONZALEZ: Members of Father Banks’s congregation say they appreciate his efforts to build bridges of understanding between African Americans and Latinos.

MARIAN ANTUCHA (Latino parishioner speaking in Spanish with English translation): He helps all the people, African Americans, Latinos, the entire community. To us, Father Peter doesn’t recognize borders. He’s a person who helps everybody, and that’s why we’re here.

AFRICAN-AMERICAN PARISHIONER: If PR and public relationships, communications was a gift from God, poof, he got it ten times, you know, because he can get out there and talk to different people, and they just feel his love, and he will tell them to come here, and then they feel the love. It’s just a relationship that blossoms.

AFRICAN-AMERICAN PARISHIONER: If PR and public relationships, communications was a gift from God, poof, he got it ten times, you know, because he can get out there and talk to different people, and they just feel his love, and he will tell them to come here, and then they feel the love. It’s just a relationship that blossoms.

GONZALEZ: As he’s gotten older, Banks says he’s increasingly focused his ministry on the education and safety of Watts’ youngest, at the elementary and middle school operated by his church.

FATHER BANKS: They know more about pain than I do in my lifetime, and they are only six, seven, eight, nine years old. You saw them this morning there, dying for affection. If I don’t feel optimistic and I feel tired, I come over to the school. I get energy from the school, energy from these children.

Hope is to be able to sing in the middle of the darkness, and I think that’s what hope is for me. I can still sing in the middle of the darkness.

GONZALEZ: However, after serving the spiritual and material needs of this community for much of his adult life, Father Peter Banks will soon depart Watts. He’s been asked to take a job as a church recruiter in a rural area of California. Although he says he feels duty-bound to fill this position, Banks acknowledges he feels conflicted about leaving this community.

FATHER BANKS: That’s an emotional issue for me. It’s going to be a big struggle to leave here. It’s going to be—I’m at peace with God. That’s all I can say. I am at peace with God. I feel it is God’s will that I continue his work, and we need priests for the church and brothers and…

GONZALEZ: But it hurts?

FATHER BANKS: Oh, it hurts deeply. I have put so much of my life in here. I have invested so much in children. It is the biggest change of my life. I feel I am leaving home twice. I left Ireland 37 years ago, and I feel like I am leaving home again, too. But I’ve come to terms with it, and I know that I am doing it for a higher cause, a higher power.

GONZALEZ: The people whose lives Father Banks has touched in Watts hope his example will inspire others to continue his work of cultivating peace and understanding in a community that so needs them.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Saul Gonzalez in Los Angeles.