In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Is That All There Is?

BOOK REVIEW

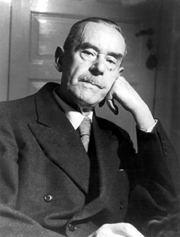

Charles Taylor, Peggy Lee, and the Secular Age

by David E. Anderson

In September 1969, singer Peggy Lee released the popular single “Is That All There Is?”, a poignant song of disillusion at the edge of despair written by the songwriting team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. It climbed to number 11 on the US pop singles chart and won Lee a Grammy Award for best female pop vocal performance.

Canadian scholar Charles Taylor, professor emeritus of philosophy at McGill University, invokes the song twice in A SECULAR AGE (Harvard University Press, 2007), his massive study of the rise of secularism. It is a magisterial 874-page doorstopper of a book (776 pages of text and almost 100 pages of notes and index), and it received the prestigious Templeton Award in 2007 and the equally prestigious Kyoto Prize for achievement in arts and philosophy in 2008.

Taylor cites the song as emblematic of the “flatness” and lack of “fullness” many experience in contemporary life. The lyrics are, in fact, a retelling of German novelist Thomas Mann’s 1896 short story, “Disillusionment,” suggesting that “flatness” has long been a feature of modernity. Strangely, Taylor’s book mentions Thomas Mann but not his story—and then only names Mann in a list of other writers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Joseph Conrad, D.H. Lawrence, and the American poet Robinson Jeffers, who are said to represent a widespread belief “in our reliance on the forces of irrationality, darkness, aggression, sacrifice.”

Such historical and cultural references are both a strength and weakness of Taylor’s encyclopedic yet exhausting approach to telling the intellectual story of the last 500 years and the rise of secularism that has come to define if not dominate contemporary life. In one sense they show the broad range of his intellect and his command of much of the material he brings to bear on his argument. But sometimes the references are not fully engaged, as if Taylor believes his point can be made through citation and invocation rather than argument and engagement.

Taylor has set himself a daunting task. He begins with an obvious assertion: belief in God is not the same today as it was in 1500. What that change consists of and how it came about is the story he wants to tell. In 1500, everyone in Latin Christendom believed in God. Unbelief was virtually impossible to envision much less embrace. Now, in the early years of the 21st century, belief—at least in the West—is just one option among many and not always the most intellectually or emotionally attractive option at that.

Taylor wants to argue that previous descriptions of how we got here—the gradual secularization of the world—are wrong. The conventional wisdom of secularization and what he calls “subtraction” theories do not adequately account for the way we live now. Those theories say secularity is inextricably connected to modernity, especially the rise of science, and is explained by humanity’s inevitably shedding—either losing or being liberated from, depending on your point of view—the “enchanted” view of the world that existed before the 16th century.

Taylor wants to distinguish between three kinds of secularism which, he argues, while related, are often confused and therefore lead to a potential misreading of the current secular age.

First, there is the secularism that is a result of religion being emptied from public institutions and practices, especially political life. Formally, this is the secularism of the Founders’ notion of the separation of church and state, and informally it is what conservative intellectuals such as the late Richard John Neuhaus, organizations such Focus on the Family, and committees such as the National Day of Prayer task force lament as “the naked public square.”

Second, there is the falling off of religious belief and practices, seen in lower church attendance rates or a decline in confessions, prayer, or Bible reading. Many Western European countries, even those with a vestige of state or established churches, can be understood as increasingly, even pervasively, secular.

Third, and most important, there is a change in what Taylor calls “the condition of belief.” In this sense, secularity consists in belief moving from an unchallenged assumption of everyday life to one option among many. “The change I want to define or trace is one which takes us from a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others,’’ Taylor writes.

It is the change in the conditions of belief, from an “enchanted” world filled with supernatural spirits and demons and God and a porous self in which these forces are active on the person, to a buffered self in which the world is experienced within nature and its processes and is no longer vulnerable to the world of spirits. This creates the environment for an “exclusive humanism” in which the world is explained and “fullness” or “flourishing” is experienced without recourse to outside or transcendent factors.

Taylor argues this change is not a “subtraction,” the sloughing off of superstition, but is, rather, the result of new inventions, newly constructed self-understandings and related practices that evolve, ironically, out of the pressures of what he calls Reform with a capital “R,” medieval, pre-Reformation movements within the church aimed at narrowing the gap in religious practices between the laity, ordinary people, and elites, especially spiritual elites such as monks and nuns. The Reformation of Luther and Calvin, Taylor argues, is the ultimate and perhaps necessary fruit of the Reform spirit, producing for the first time a true uniformity of believers, a leveling up that eliminated the spiritual gap between laity and elite.

From these currents of Reform, Taylor traces in painstaking detail the disenchantment of the world and the rise of humanism through the Protestant Reformation, the more radical Calvinist Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, Renaissance humanism, the scientific revolutions, deism, and the gradual replacement of what he terms “the transcendent frame” with “the immanent frame” and exclusive humanism.

The result, however, is not the substitution of exclusive humanism for religious belief but, rather, what Taylor describes as a “nova” or an explosion of a host of possible positions.

“The salient feature of Western societies is not so much a decline of religious belief and practice, though there has been lots of that, more in some societies than in others, but rather a mutual fragilization [a Taylor neologism] of different religious positions, as well as of the outlooks both of belief and unbelief,” he writes. While the developments of modernity have made earlier forms of religion, e.g., medieval orthodoxy, virtually unsustainable, new forms have sprung up.

While a host of positions are possible, Taylor is primarily interested in only three and, peripherally, in a fourth, the older orthodoxy. What engages him are what he calls exclusive humanism, the primary form of secularism today; Nietzschean atheistic anti-humanism, which Taylor uses as a foil to critique both humanism and orthodox belief; and his favored position, a transcendent “modern religious consciousness.” The result is a society in which great numbers of people are not firmly embedded in any one of these stances but feel puzzled and cross-pressured.

After his lengthy historical examination of the way secularism, or unbelief, became a credible position for many people, Taylor in the last two parts of the book (running some 350 pages) turns to the contemporary situation. These sections, while still grounded in analysis, are far more prescriptive than descriptive. Taylor takes off his historian’s hat and trades it for a theologian’s as he seeks to outline and examine the dilemmas faced by those living in the contemporary culture of the West.

In his analysis of the rise of the secularism that has made unbelief one of many possible positions to credibly hold, in a manner unthinkable in 1500, Taylor understands the current situation as primarily a triangular debate. Instead of a contest merely between religion and secularism, belief and unbelief, transcendence and immanence, he sees the party of unbelief divided among regular secular humanists, exclusive humanists, and Nietzscheans who fault secular humanism for its failure to offer a kind of atheistic transcendence, a vision of courage and glory that requires more than ordinary life for its fulfillment, even as it criticizes religion for its theistic transcendence.

On the borders of this triangle Taylor also allows a vestigial religious position, the medieval orthodoxy that finds some adherents in conservative Roman Catholicism and fundamentalist Protestantism, yet he seems to see it as a major player and a strongly credible stance in current cultural debates. Similarly, his personally favored position of transcendent theism is rooted in a particular form of Roman Catholicism that stresses the theological work of philosophers Ivan Illich, Charles Peguy, and Jacques Maritain or artists such as Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, but not, interestingly, French priest and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin, whose groundbreaking efforts at integrating Christianity and modern science might have engaged Taylor’s attention, one might think, at least as much as the more marginal social critic Illich. Taylor also completely ignores the work of such giants of modern Protestantism working in the same cultural arena as Rudolph Bultmann and Karl Barth. One might have expected to see some discussion of Paul Tillich’s theology of culture, or Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Christianity without religion.” In a work that seeks to be as encyclopedic as Taylor’s, these lapses are not oversights. They are emblematic of the particular theological place Taylor wants to take his readers.

Taylor draws a compelling portrait of a part of the contemporary cultural situation in two long and complex chapters on what may be the most challenging problem facing both secularists and unbelievers today—the problem of violence. Again, his skill as a historian of ideas is much in evidence. Drawing heavily on the work of French historian and philosopher Rene Girard on religion and violence and the ideas of scapegoats and victims, Taylor acknowledges that “it would certainly appear that since the very beginning of human culture, religion and violence have been closely interwoven. And there are certainly cases today where the connection holds.”

At the same time, Taylor accurately notes that “when we examine more closely some of what we might call the religious uses of violence, in particular its appeal to scapegoat mechanisms, and the self-affirmation of our purity by identifying all evil with the enemy outside…we find that all this can easily survive the rejection of religion, and recurs in ideological-political forms that are resolutely lay, even atheist. Moreover, it recurs in them with a kind of false good conscience, an unawareness of repeating an old and execrable pattern, just because the easy assumption that all that belonged to the old days of religion, and therefore can’t be happening in our Enlightened age.”

Taylor finds no simple prescription for either believers or secularists to resolve the problem of violence. “Both sides have the virus and both sides must fight against it,” he asserts. But he does say “there can be moves, always within a given context, whereby someone renounces the right conferred by suffering, the right of the innocent to punish the guilty, the victim to purge the victimizer. The move is the very opposite of the instinctive defense of our righteousness. It is a move that can be called forgiveness, but at a deeper level, it is based on a recognition of common, flawed humanity.” Nelson Mandela is his chief example.

Looming even larger than violence, however, is the broader cultural malaise, the seeming lack of meaning many moderns and, it would seem, mostly nonbelievers, in Taylor’s telling, find in their lives. “The secular age is schizophrenic, or better, deeply cross-purposed” and “very far from settling into a comfortable unbelief,” he observes. At the heart of the malaise is the question asked in the chorus of the Leiber-Stoller version of Thomas Mann’s story. It might be called the Peggy Lee syndrome: Is that all there is?

For Taylor, the valorization of ordinary human life and its experiences that secularism proposes cannot meet humanity’s longing for depth of meaning, its aspirations for a higher form of ethical living, and thus it requires a transcendent grounding. But it seems possible to argue Taylor misreads his own history. He appears to indicate the reform impulses that created contemporary secular humanism are exhausted and what he somewhat dismissively terms “ordinary human life” does not contain within it the resources to respond to and be deeply moved by beauty. Human beings, he suggests, can’t experience courage in the struggle for justice, universal human rights, and economic equality, can’t experience conversion and transformation without reference to a transcendent theism.

Indeed, Taylor seems to have a pinched view of secular humanism’s experience of the world. He gives the game away when he writes that “modes of fullness recognized by exclusive humanisms, and others that remain within the immanent frame are therefore responding to transcendent reality, but misrecognizing it,” which is a little like Humpty Dumpty’s reply to Alice in Wonderland: “When I use a word…it means just what I choose it to mean, nothing more, nothing less.” If immanent experiences of fullness, wonder, and awe are really experiences of transcendence, then ultimately there is no such thing as a secular humanist.

But if we are to take Taylor at his word, both transcendence and immanence are credible “frames” in the contemporary secular age. Theists may, as Taylor does, lift up Gerard Manley Hopkins’s famous lines, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God. / It will flame out, like shining from shook foil,” to support their stance. Humanists, on the other hand, may lift up the American poet of self-realization, Walt Whitman, for a vision of the fullness of secular humanism, as novelist E.L. Doctorow does in an essay in his collection REPORTING THE UNIVERSE: “Whitman when he walked the streets of New York loved everything he saw—the multitudes that thrilled him, the industries at work, the ships in the harbor, the clatter of horses and carriages, the crowds in the streets, the flags of celebration. Yet he knew, of course, that the newspaper business from which he made his living relied finally for its success on the skinny shoulders of itinerant newsboys, street urchins who lived on the few cents they made hawking the papers in every corner of the city. Thousands of vagrant children lived in the streets of the city that Whitman loved. Yet his exultant optimism and awe of human achievement was not demeaned; he could carry it all, the whole city, and attend like a nurse to its illnesses but like a lover to its fair face.”

Despite some flaws, Taylor’s book is a major achievement, one that demands sympathetic yet critical engagement. He has changed the way believers and unbelievers alike will understand their history, but A SECULAR AGE is a first word rather than the last word in making sense of our contemporary culture.

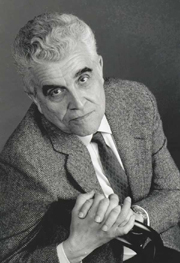

David E. Anderson, senior editor at Religion News Service, has written most recently for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on John Updike and Gerard Manley Hopkins.