BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: In public life, separation of church and state is widely approved, but what about separation of religious beliefs from official acts? Should a public official be guided by his or her faith? We have a story today about granting clemency to those convicted of a crime. It's a form of mercy or forgiveness, and governors can see it in very different ways, as Bob Faw of NBC News reports.

BOB FAW: Walter Arvinger, now 58, is finally free after serving 36 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

WALTER ARVINGER (Former Inmate): Still, in my heart I knew I had nothing to do with it. As a matter of fact, I know I had nothing to do with the crime.

FAW: In 1968, teenager Arvinger was convicted as an accomplice when a Baltimore teenager was beaten to death with a baseball bat. But Arvinger's sentence, life in prison, was commuted in 2004 by Maryland's then governor, conservative Republican Robert Ehrlich.

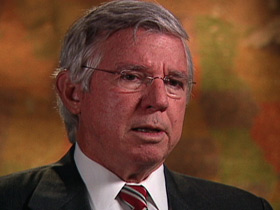

ROBERT EHRLICH (Former Governor of Maryland, Republican): It was my sense of what executives do in the context of doing good -- and doing justice.

FAW: Ehrlich, elected on a no-nonsense, tough-on-crime platform, showed mercy to Walter Arvinger, but Ehrlich's predecessor, Parris Glendening, who portrayed himself as a liberal Democrat, refused to intervene.

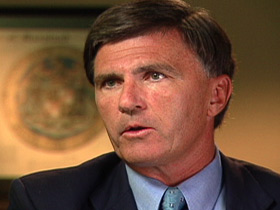

PARRIS GLENDENING (Former Governor of Maryland, Democrat): I actually made a policy statement, which we made very public, that if you're sentenced to life in prison that means life in prison.

FAW (to Mr. Glendening): No exceptions?

Mr. GLENDENING: No exceptions.

FAW: Two governors with two radically different approaches to clemency. In his first three years in office, Ehrlich, the champion of conservatives, pardoned or commuted almost six times as many sentences as liberal Glendening did in his eight years.

Mr. EHRLICH: For me, it was simply part of the job description. This is what you do as governor of the state of Maryland. I view it as justice, a more even distribution of justice.

FAW: Ehrlich, a former prosecutor, says he knew the criminal justice system often errs and that a governor should be a court of last resort. Non-lawyer Parris Glendening did not feel he had the right to second-guess.

Mr. GLENDENING: I think it would be very presumptuous of me to say that I ought to be reviewing every case and become kind of an ultra-Supreme Court to reverse that decision or to reduce that sentence.

FAW (to Mr. Glendening): A safety valve, for example -- that's not the role a governor should fulfill?

Mr. GLENDENING: I do not believe so, no.

FAW: For elected officials, clemency can be dynamite. Gerald Ford felt his pardon of Richard Nixon cost him the election of 1976. Bill Clinton was savaged for his 11th-hour pardon of the fugitive financier Marc Rich. George W. Bush was attacked for reducing the sentence of Gordon "Scooter" Libby. So clemency, then, can be controversial, but proponents insist it is absolutely necessary.

MARGARET LOVE (Former Pardon Attorney, Office of the Pardon Attorney, USDOJ): The problem is that we don't have a perfect law, and we don't have a perfect legal system, and that's why you need clemency. If we do believe that we have a humane and just system, then we have to be always prepared to use clemency.

FAW: For seven years, Margaret Love headed the pardon office in the U.S. Dept of Justice.

Ms. LOVE: As a Christian, I do believe in forgiveness. I do believe in starting again. I think it is extremely important for the law that structures our public life to incorporate the same values.

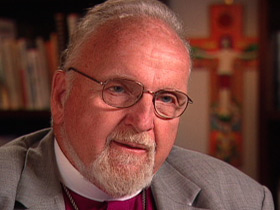

FAW: That belief -- that political decisions should be infused with ethical, specifically with Christian values -- is echoed by religious leaders like Jerry Knoche, a bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

Bishop GERARD KNOCHE (DE-MD Synod, ELCA): Use of clemency is a Christian idea because it's the political expression of forgiveness, and forgiveness is what the heart of the Christian message is about.

FAW: But in the real world what religious figures say should happen, and what many elected officials concede does happen, often conflict.

(to Mr. Glendening): The concept of forgiveness -- was that part of your calculation at the time?

Mr. GLENDENING: It was not. I think it would have been overly presumptuous of me to draw some moral basis of forgiveness and say I forgive you and therefore your death penalty is commuted, or your serious sentence is reduced.

FAW (to Mr. Glendening): Did you find yourself praying over any of these decisions?

Mr. GLENDENING: I did not.

Mr. EHRLICH: I am a Christian, so clearly my religious views, orientation, values are part of me. It clearly plays a part in the process because it's part of me, but it was not dispositive.

(to Mr. Ehrlich): Meaning it wasn't the primary factor?

Mr. EHRLICH: Correct.

FAW: What, then, does matter when clemency is considered for an inmate?

(to Mr. Ehrlich): Did the applicant, governor, have to express a certain degree of remorse or regret?

Mr. EHRLICH: Looking me in the eye was by far the least relevant factor here. It was nothing I required, nothing I asked for. Words are cheap. Actions count. You can lie to me. You can con me. But what have you done over the last 10, 20, 25 years to prove to me that you will be productive member of the society? That's what counts.

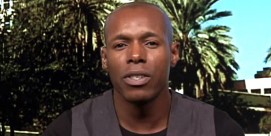

FAW: But figuring out what counts in clemency cases can be difficult for attorneys like Michael Millemann, who represented Walter Arvinger.

MICHAEL MILLEMANN (Attorney): The picture tells the story. This is his whole transcript. The trial took half a day. He never should have been convicted. The guy with the bat was released before Walter was. Mr. Arvinger wound up staying in prison longer than anybody else when he never should have been in prison in the first place.

FAW: Not only did Arvinger deserve clemency, says Millemann, who heads up the University of Maryland Law School project investigating prison sentences, but so do many others.

Mr. MILLEMANN: They're sitting in the system without any hope that no matter what they do inside the prison system, with no hope that they will ever be let out. That's not only, I think, immoral with respect to those people, it is a bad formula within a prison system when you take away all hope of release.

FAW: Clemency, then, can undo mistakes, even reverse injustice, can be a measure of one kind of society we are.

Mr. MILLEMANN: I think it's consistent with faith to understand human nature, to understand human fallibility, to have some sort of institutionalized forgiveness when someone has paid their penalty.

Bishop KNOCHE: Retributive justice, where we want to punish an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, does not make for a good society. What makes for a good society is where relationships in the community that are broken by crime find a way of being restored.

FAW: Just as Walter Arvinger was restored, 36 years later.

Mr. ARVINGER: What happened to me shouldn't have happened. But when you are in the world of God, it tells you do what's necessary to keep yourself strong, because something always new happens.

FAW: New for Walter Arvinger, if not for other inmates, as society wrestles with who deserves a gesture of mercy -- and who doesn't.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Bob Faw in Washington.