In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

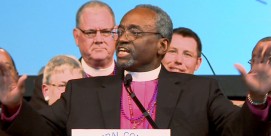

Bishop Robert Duncan

Read more of Kim Lawton’s September 27, 2007 interview with Bishop Robert Duncan of the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh:

Q: What did you think of the final document the House of Bishops meeting in New Orleans produced?

A: The final document from New Orleans was very much what the House of Bishops has said before, and it revealed the commitment of the American church to continue on its move forward in terms of the innovations in faith and order. It did acknowledge the trouble in the Communion and the pain that the American church has caused. It did maybe slow things down a little bit, but it’s not going to change the direction, and clearly in New Orleans as there has been for some while there really are two churches under one roof and those two churches are one that is moving in a way with the culture and with secular society, moving toward embrace of the culture itself, and the other is moving in a direction — I mean we are trying to stand where we’ve always stood. That’s the reality. So that’s New Orleans, but that’s old news.

A: The final document from New Orleans was very much what the House of Bishops has said before, and it revealed the commitment of the American church to continue on its move forward in terms of the innovations in faith and order. It did acknowledge the trouble in the Communion and the pain that the American church has caused. It did maybe slow things down a little bit, but it’s not going to change the direction, and clearly in New Orleans as there has been for some while there really are two churches under one roof and those two churches are one that is moving in a way with the culture and with secular society, moving toward embrace of the culture itself, and the other is moving in a direction — I mean we are trying to stand where we’ve always stood. That’s the reality. So that’s New Orleans, but that’s old news.

Q: Is it going to be enough to satisfy some others in the Communion who have been concerned?

A: Well, it’s not enough for the dioceses like my own that really don’t see a way to go forward within the Episcopal Church. We believe that we will be forced to be something other than we have been, to stand in some new place, and we’re not going to go to a new place. We’re going to stand where Christians have always stood, where scripture and the tradition just have always caused the church to be. For the worldwide church already a number of influential leaders from major places in the communion have said this isn’t enough. It’s very sad for our Communion. It’s heartbreaking the way in which Anglicanism is tearing apart. The hope of course is that God will put it back together in a new way, in a stronger way, in a reformed way as part of the reformation he is working in the whole of the Christian world.

Q: Tell me about this meeting in Pittsburgh. What are you and all these groups trying to accomplish here?

A: There are 10 jurisdictions who have been working together, a growing number, we started as six in 2004, who have committed to make common cause for the gospel of Jesus Christ, the gospel as it has been received, and to make common cause for a biblical, missionary and united Anglicanism in North America. We are fragments, like some of us represent fragments, dioceses of the Episcopal Church that can’t go down the road that the Episcopal Church is on, can’t leave the faith once delivered, and other fragments [are] folks who as long as 134 years ago actually found themselves put out of the Episcopal Church because of their stand on the gospel and their belief that the Episcopal Church was shifting and wavering and moving away from its Reformation position. This meeting is a meeting in which these fragments, as bishops, and for the first time it’s all the bishops of these 10 fragments from the US and Canada, they are together and we’re together and what we’ve done is agree to the way in which we’ll move forward, move forward forming a federation of the Common Cause Partners, pushing that schedule along, and before too long appealing to provinces within the Communion to recognize this federation as a new ecclesiastical structure in the States, the very thing that a number of the primates just a year ago in September called for from Kigali as they looked to the problems in the US church and to the wavering and wandering of the majority.

Q: So the goal here is to create an alternative Anglican structure?

A: The goal has been to bring together all of those who stand on scripture, who stand with the tradition, who are committed to mission and who can’t bring themselves to separate from what Christians have always believed. So we’re working together as bishops, forming a college of bishops, again first ever meeting here, who can work together in mission. We’ve shared all kinds of ministry initiatives together, from ministry to youth, all kinds of exciting things with postmoderns to work with the global church in relief and development to the more ordinary matters of church planting. Indeed one of the calls of this conference was for us together to plant 1000 new churches, which would be quite something to see.

Q: These groups do have theological differences of their own, on issues like ordination of women, certainly worship style. Some are more charismatic, some more Catholic. How strong are those differences, and how big is the challenge going to be?

A: These are important differences, but they are not salvation differences. They are differences that are part of what all of Anglicanism is comprehending at the moment. About half of the provinces of the Communion ordain women, the other half does not. Again, the role of women in holy orders is a question that the church in the 21st century, the Anglican Communion, is looking at. Can women be priests? Can women be bishops? We’re working that through, but since 2003 we have committed to each other despite this difference to go forward together. Again, it doesn’t change the gospel message that we bring, that Jesus Christ came as God’s answer to our problem, that we needed a rescuer and a savior, and we are all absolutely united about who that rescuer is, who that savior is, and the new life he brings, the transformed live he gives through the power of his Holy Spirit. We see that as incredible good news, and we all together want to share that. We have no differences about that.

Q: There are suggestions that there have been some challenging personality issues as people try to work all this out.

A: Well, sure. What’s true about a family is a family cares enough about one another that they actually disagree. This isn’t a paper — this isn’t some “lite” association, this is a deep association for the future of our part of the Christian church, and we care enough about each other and are deeply enough related that we sometimes, you know — voices get raised this way and that way, but I can guarantee that the end of it is not voices raised in anger but voices raised in praise.

Q: What do you hope the relationship of this federation will be to the broader Anglican Communion?

A: The next step in this — we have articles of federation. I as the chair of this Common Cause Partnership — we now have all but two of the 10 partners having had their councils meet and approve the articles of federation, which again a federation is a body that doesn’t take away the distinctives or the independence of each of the jurisdictions but really creates a deep level of interdependence. I’m going to call the first leadership council for the first week in January. That council will appoint the committees that the articles call for. They will be the committees that really will structure things. Within a year we will actually gather the second council, and at that time we will be ready, I think, to go to the rest of the Anglican Communion and say here we are. We really are that new ecclesiastical structure in North America that draws all of the separated orthodox Anglicans together and that is ready to be partners with the rest of the world on the terms the rest of the world expects Anglicanism to represent, to uphold, to share and propagate.

Q: Many of your members already have direct relationships with some of the conservative Anglican international leaders. Are they encouraging this effort?

A: Well, absolutely. From the beginning the message to me and to other leaders from the archbishops around the world has been get it together. Find a way to work together. Agree on a leader, agree on the way you are going to work together, and declare it and move forward, and we’ll go forward with you.

Q: How complicated will it be for you to separate a diocese from the Episcopal Church, as you’ve announced — the diocese of Pittsburgh?

A: The last time that Episcopal dioceses separated from the Episcopal Church was in the American Civil War. Nine dioceses actually separated for a period of years. When the war was over the Episcopal Church came back together. There was an important social issue, I mean the whole issue of slavery divided the nation. The North and the South were divided. When the issue was settled the church came back together. Where we are right now is seeing the church moving in two distinctly different directions on issues of Christian morality quite different than the slavery issue. What our diocese and a number of other dioceses are going to have to do is try to figure out, okay, we joined, we federated. Can we break that federation? Again, the whole purpose of it is not because we’ve changed, but the Episcopal Church is so radically changed we as a diocese in order not to embrace that change or be forced into that change are saying the best course forward for us is to let them go their way and the way in which we will operate is in alignment with another province in another part of the world that still upholds what the worldwide Christian church, what worldwide Anglicans believe and teach and want to share.

Q: And do you anticipate the property struggles in all of this?

A: Those issues are all there. Jesus was real clear about how difficult it is for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of heaven. Again, if that’s what you’ve really got your mind and your heart set on, that’s what you get. What we’ve got our mind and our heart set on is preaching the gospel. And even if we lose our property, we lose our offices, so what? We believe these are the things that are our heritage. Again, the people here in Pittsburgh haven’t changed. The church here is as it has been. Why should the property that generations here have given to the Episcopal diocese of Pittsburgh be taken from it? But if the courts should do that, if that’s how it turns out, if for the good of the gospel we determine that’s what we want to do is just give it away, we have a dominical mandate that sort of suggests that would be a good thing to do.

Q: is there anything else you want to add?

A: We are in the midst of an immense reformation of the Christian church. Anglicanism is just a part of that. It’s particularly a reformation of the church in the West, because the West has drifted with its culture, and Christianity is principally countercultural. In what had been a Christian society, or for instance in England a state church, it was a vision for a time that the Christian church and the state could be one. That’s not where we are any longer. We’ve secularized Western societies and the church needs to stand for what it has been called to do, for a saving message that takes people out of the “secula” in which they find themselves and into something that looks more nearly like the heaven God intended.