In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The Soul of a Doctor

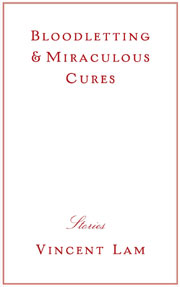

Read Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly’s Web-only interview with Vincent Lam, a Canadian doctor and writer whose acclaimed first book, BLOODLETTING & MIRACULOUS CURES (Weinstein Books, 2007), was awarded the 2006 Giller Prize for fiction:

One of the stories in your book is about an anatomy class. In it you refer to the sacred study of medicine and to monk-like medical students. You use almost sacramental language to talk about human anatomy. What is the common thread between those two worlds and the two vocabularies of medicine and the spiritual or religious life?

I certainly think that the medical student enters a world that is full of ritual and that is full of new meanings to familiar things. For instance, the human body, which you mention as an important part, of course, of the anatomy class, is very familiar to all of us, but by becoming a medical student one finds oneself in a position of dissecting that human body and coming to know it in a very different way. None of this is easy. Like a religious vocation, all of it requires both a great deal of work as well as a giving of self and an immersion in something that was not previously part of one’s world view.

Spiritual life has as much to do with story and narrative, it seems, as medicine does. How do these three things come together?

I really do agree that medicine and narrative and spirituality intersect. Narrative — of course we can all see immediately that we are interested in stories about people because we are human, and we are inherently curious about what other human possibilities there may be. Medicine is also about narrative, and when a patient comes in to see me as a physician and when they tell me their symptoms and their experiences, what they are telling me is the first part of a story. Really, my job is to understand that story and to be able to interpret it and to tell them how the story goes from there, or to tell them the second part of the story, and without that the task and the encounter between doctor and patient is not satisfying, unless there is that story. When we come to spirituality, I think that there is a similarity because, again, in all religions people seek to understand where they came from, where they are going, and where they fit right now. So I think you are quite right. I think these three phenomena, these three enterprises, do have narrative in common.

The anatomy class story involves a cadaver with an interesting tattoo: “The Lode Keeps Me — Mark 16.” A biblical story about the preparation of Jesus’ body for burial and his resurrection figures importantly. Is there any basis in reality for the tattoo? What do the medical students learn from it?

My own anatomy class was a very important experience for me, because it was the first point in my education when I understood that the doctor relates to the human body and to the patient in multiple ways, and maybe you might even say sort of in transcendent ways, because the doctor relates at so many different levels. The doctor relates to the symptoms that are being expressed, to their understanding of the physiology, to their understanding of the statistics and odds that surround treatment. So there are different intersecting layers of understanding that are happening, and that first struck me full in the face as a young early medical student when I began to dissect, and this human stuff was flesh and bone and blood. I should say that the tattoo used is a work of fiction, and there was no such tattoo, for better or for worse. For me there is something of a second life, a second gift, in the anatomical gift that some people choose to make to science and to the study of medicine. The anatomy lab spoke to my feeling that we as human beings live very mortally and very physically, and yet that’s really not all there is to it. I am a practicing Christian, so the Jesus story is a very important story for me, and when I think about that story, even if we step away from its core religious importance, simply as a story the story of a man dying and coming to life again is a story about us as beings transcending the mere flesh that we inhabit.

Last year you wrote a piece in the Toronto Star about your church and its meaning for you. Can you say more about that?

St. Stephen-in-the-Fields is a lovely little church, and the reason it was called St. Stephen in the Fields was that at the time that it was built it was on the outskirts beyond the university of the very early place that we now know as modern Toronto. You had to go down beyond where there were the paved roads of any kind or defined roads even and go down this little dirt path — this was in the 19th century — to get to St. Stephen-in-the-Fields. That’s how it acquired the name. Now it’s a church that sits in a place called Kensington Market, a vibrant multicultural place, which to me embodies a lot of what a functioning multicultural society should be. It’s sort of a boiling pot of all sorts of things happening, and my church happens to be one of the things in that pot. One of the difficulties a lot of urban churches face its that it’s hard firstly to get enough people to come into the church, and frankly many of those churches serve people with needs, and those people’s pocketbooks are not as amply padded as some other pocketbooks. There’s a natural difficulty in a lot of these churches surviving financially. That’s kind of the situation that St. Stephen-in-the Fields finds itself. I think it’s a great church, and I think it should stick around.

In the piece you describe yourself as a modern church-goer (“faithful, critical, and hard to please”) searching for a place to pray and finding a spiritual home that “forces me to scrutinize my faith,” that “shields us from some of the compromises of the rest of the world” and “stands in the fields of my inner landscape, where I’ve always wanted a church to be.”

The thing that sent us shopping was that our previous lovely church did meet its financial end, unfortunately. That was a Baptist church. I come from a multifaceted background in that I was born Catholic, went to a Catholic school in Canada, and I married a woman who was raised in the Greek Orthodox as well as the Anglican tradition. So we were married in an Orthodox church and then spent some time at a Baptist church, and now we’re at an Anglican church, which I guess [in the U.S.] would be called Episcopalian. So as you can see we don’t feel hemmed in by the particularities of denominations.

Does being part of a faith community like that influence how you practice medicine or figure in the kind of a doctor you are?

It does. It is very important for me, because it is kind of like my bone structure in that I don’t really think about it, but I need it all the time to stand up. Certainly when I go and do medicine my mind is preoccupied with patients and symptoms and diagnosis and treatments, and that’s what whirls around in the mental gears, so to speak. But in tough spots, sometimes when I have to confront not just a technical challenge but a challenge in my medical practice to me as a person and as a human being who happens to be a doctor, I find that I often know that what I need to do is to rely upon my “bone structure” and to rely upon my spirituality and my faith to help guide me and help me as a person through difficult human times as a doctor.

Do you reveal that to your patients?

Do you reveal that to your patients?

I typically don’t. The kinds of situations that can be difficult for me as a doctor — I’ll give you an example. I work in an emergency department. It’s a pretty busy, hectic place. So it’s difficult for me when patients are angry, and sometimes patients and families are quite upset, and they are being in difficult circumstances, and this can happen. Sometimes people are outright abusive towards the staff, so this is one type of thing that is difficult to deal with. So I turn to my faith, but I don’t think it helps the situation for me to tell an angry patient that I’m trying to do the right thing for them because of my faith. It’s not part of the conversation, really. There are many other examples of things that are difficult. I mean it’s not just an issue of confrontations between doctors and patients, but really for me as a doctor — another common situation is if there are difficult decisions to be made within a family. Rarely are these decisions absolutely clear. Usually it’s subtle, it’s complicated. All these kinds of things — I don’t feel that it’s my place to inject too much of my own underpinnings, because the situation is about my patients. It’s in my background and it helps to guide me, but it’s not the situation at hand.

Do patients seek it out, do they desire to draw on those underpinnings, and how do you deal with it?

I’ve certainly seen quite a diverse range of reactions. I practice in a very multiethnic and multireligious community — Christians, Muslims, Jews and Hindus and, you know, the entire spectrum. I see everything. It’s interesting too that we do tend to be quite accepting on one hand of people’s religious expressions, as we should be, and at the same I do think that we don’t know quite what to do with it as professionals and as people who do health care. We accept and we support, and that’s certainly a good place to be, but sometimes we’re not sure what to say beyond that as a profession.

Hospital chaplains also play a part in narrative medicine. What do you observe of their role?

The chaplains that we have are wonderful. Certainly in the emergency department sometimes bad news can be very significant and very sudden. We have a lovely chaplaincy service that we are able to call on. That’s something that I frequently do. I frequently ask people if they would like a chaplain. Sometimes people do, sometimes people don’t. Sometimes people have their own spiritual community that they turn to in that kind of situation. I think that to make that offer as a health care professional is a worthwhile thing, because it allows that door to be open, and it says, even if it’s someone of a different faith or one is unsure what their faith is, if as a doctor or as a nurse one says would you like a chaplain, we can find someone to speak to you and if not of my faith then of your faith, I think that says a lot because it acknowledges that that story is going on and that discussion can happen.

What’s been you experience of the teaching and practice of medical ethics?

The teaching of ethics is probably quite good and the teaching of clinical skills is also quite good, and there has been a big movement in the past couple of decades to really instill that in the curriculum, so I think that is a big step forward. I think that the biggest challenges to physicians, once they actually start to practice medicine, are the conditions in which they practice. For instance, it’s one thing to teach a physician how to take a sensitive, caring, patient-focused history and to communicate with the patient properly. Once that physician goes into practice and their HMO or their administrator tells them, “That’s great, and by the way you have to see 12 patients every hour without fail,” then it doesn’t really matter that the physician knows exactly how to do it and what to do. The conditions of work make it impossible. There are similar issues, perhaps, in the ethics of doing medicine. There’s a fantastic book by Jerome Groopman, HOW DOCTORS THINK, and one of the things he talks about is some of the motivations for doing things, and doctors are generally motivated by the right things but can be led in this direction or that direction by pharmaceutical representatives, by how much they are paid to do one type of procedure versus another type of procedure, and Dr. Groopman explores that with great insight and sensitivity in his books. Those are, again, the kinds of ethical problems that come up in practice. So it’s one thing to be taught how to behave ethically. It can be difficult if doctors work in a setting that becomes ethically slanted.

What are you reading yourself right now?

I read anything I can get my hands on. Right now I’m reading a book by Shalom Auslander called FORESKIN’S LAMENT. It’s actually about his relationship with God. He’s American and was raised, I believe, in upstate New York in an Orthodox Jewish family, and he has a very visceral and personal relationship with God that he explores in this memoir.

There has been a long and well-known line of doctor-writers over the years. How you draw on that body of literature? Do you feel a part of that rich tradition?

Yes. It is a rich tradition. I don’t think that I realized how rich a tradition it was until I was doing it…I never really thought about the doctor-writers who are out there. I think it happens because doctors and writers both deal with human story and human narrative. I love reading, but I read pretty much anything that grabs my interest. I can’t say that I pick out the doctors in the crowd. I just sort of read all of it. One of my contemporaries in Canada is Kevin Patterson, who is a doctor and who just has a new novel out called CONSUMPTION. Then of course in the US some people who are well known to you, I’m sure, are Jerome Groopman, Atul Gawande, and Oliver Sacks, and the list goes on — William Carlos Williams — and Chekhov, who’s not American but a good example.

What have you learned from writing and medicine about human suffering, about the purpose of medicine and the meaning of suffering? I’m thinking, among other things, of the stem cell research debate in which there are some who emphasize its potential to relieve human suffering and others who seem to emphasize the need for suffering and that suffering has meaning.

I’m very much someone who believes in doing everything possible to relieve human suffering, but the difficulty is that in certain debates, like for example the stem cell debate, it’s not enough simply to say that we want to relieve suffering, because there is a cost associated with it. There’s an ethical debate, and so that becomes quite different. for example. than relieving suffering by using medication derived for instance from plants. It’s a different discussion, because the balance of the debate must weigh into it when we talk about something like stem cell research. But certainly when we talk about relieving pain, for example, using a medication, I find it hard to argue against that, and I think that is a very consistent attitude of modern medicine. There may have been a time when some doctors might have said well, we won’t give you this drug to relieve your abdominal pain because it’s going to be more difficult for us to make a diagnosis if we relieve your pain. It’s very interesting because as that particular question, namely whether giving pain medication makes it harder to diagnose different types of abdominal pain, has been investigated, it’s been shown very clearly that giving pain medicines does not reduce the ability to diagnose what’s going on in someone’s abdomen at all. I certainly think that when we talk about relieving suffering in a therapeutic context, then it makes a lot of sense. There can be times when people have to make very individual choices. For instance, in oncology two people with the same condition can have very different perspectives on what they want to be done. Some people may choose chemotherapeutic treatments which have lots of side effects, which are well known, because that may prolong their life. In a sense they are choosing to have a longer life on earth and to accept the suffering that extended life will give them and to them that’s worth it, to experience mortal life albeit with suffering. Others would say that’s not what they want. Others would say, “I would rather not have that particular chemotherapy. There are too many side effects. For me it’s not what I want.” For them the suffering would be onerous and the extension of their life would not make it worthwhile. So these things are very individual, and I think that we have to recognize, both as doctors and writers, and this is really where my sensitivity as a doctor and a writer comes back to your question — I think that we have to understand that these are individual stories, and individual stories embody individual questions and individual decisions, so once we understand that certain decisions are about a person’s individual story, then we can accept that there may not be one right answer for two or three people in technically the identical situation. They may have different stories, and those stories may require different endings.