In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

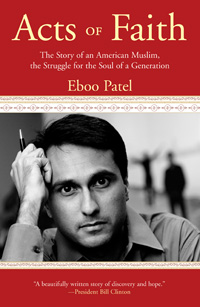

Excerpt from “Acts of Faith” by Eboo Patel

Read an excerpt from ACTS OF FAITH: THE STORY OF AN AMERICAN MUSLIM, THE STRUGGLE FOR THE SOUL OF A GENERATION by Eboo Patel (Beacon Press):

In her thirties, during the Great Depression, Dorothy Day had started something called the Catholic Worker movement, which combined radical politics, direct service, and community living. For nearly half a century, Day had given up her own middle-class privilege to live with those who went without in what was called a Catholic Worker House of Hospitality. The original House of Hospitality was on the Lower East Side of New York City, but it inspired more than a hundred others across the nation.

Like everything else that seemed good, I was convinced that the Catholic Worker movement had faded away in the 1960s.

“Oh, no,” somebody told me when I mad an offhand reference to the Catholic Worker and bemoaned its disappearance. “There are still many, many Catholic Worker houses left. In fact, there is one here in Champaign [Illinois].

“What’s it like?” I asked, shocked.

“Part shelter for poor folks, part anarchist movement for Catholic radicals, part community for anyone who enters. Really, it’s about a whole new way of living. You’ve got to go there to know.”

From the moment I entered St. Jude’s, it was clear to me that this was different from any other place I’d been. I couldn’t figure out whether it was a shelter or a home. There was nobody doing intake. There was no executive director’s office. White, black, and brown kids played together in the living room. I smelled food and heard English and Spanish voices coming from the kitchen. The first thing somebody said to me was, “Are you staying for dinner?”

“Yes,” I said.

The salad and stew were simple and filling, and the conversation came easy. After dinner, I asked someone, “Who are the staff here? And who are the residents?”

“That’s not the best way to think about this place,” the person told me. “We’re a community. The question we ask is, ‘What’s your story?’ There is a family here who emigrated from a small village in Mexico. The father found out about this place from his Catholic parish. They’ve been here for four months, enough time for the father to find a job and scrape together the security deposit on an apartment. There are others here with graduate degrees who believe that sharing their lives with the needy is their Christian calling. If you want to know the philosophy behind all of this, read Dorothy Day.”

I found some of Day’s old essays and a copy of her autobiography. In those writings, I found an articulation of what it meant to be human, to be radical, and to be useful. Recalling the thoughts of her college days, Day wrote, “I did not see anyone taking off his coat and giving it to the poor. I didn’t see anyone having a banquet and calling in the lame, the halt and the blind. And those who were doing it, like the Salvation Army, did not appeal to me. I wanted life and I wanted the abundant life. I wanted it for others too.”

Elsewhere in her autobiography, she wrote; “Why was so much done in remedying social evils instead of avoiding them in the first place? Ö Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves but to do away with slavery?”

Here was what I had been seeking for so long: a vision of radical equality — all human beings living the abundant life — that could be achieved through both a direct service approach and a change-the-system politics. For so long, those two things had existed in separate rooms in my life — a different group of friends, a different way of talking for each. Here was a movement that combined them. Finally, the two sides of my self could be in the same room.