In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

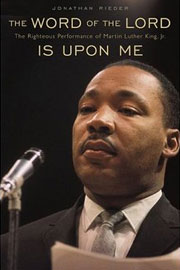

Excerpt: THE WORD OF THE LORD IS UPON ME by Jonathan Rieder

Read an excerpt about the close relationship between Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel from THE WORD OF THE LORD IS UPON ME by Jonathan Rieder (Harvard University Press, April 2008):

Heschel’s prose had an extraordinary poetic quality — it burned with intensity — that always appealed to King. They also shared a connection to [Reinhold] Niebuhr, beginning with Heschel citing Niebuhr at the conference at which he and King first met. Heschel taught at Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, which was across the street from Union Theological Seminary where Niebuhr taught. The two men were neighbors on Riverside Drive. In their later years, they walked the drive together, and Heschel often talked about his friendship with King. But what especially lingered in the memory of Ursula Niebuhr, Niebuhr’s wife, was Heschel’s repeated reminiscences about Selma. “He was shocked, deeply, to see white Southern women spitting on and yelling at the Catholic nuns with whom he walked.” Both King and Heschel would denounce the Vietnam War in prophetic terms from the pulpit of Riverside Church.

King was cementing his ties to the circles of ecumenical liberalism at a 1963 conference on race and religion sponsored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews when he first met Heschel. Like King and Rev. Joseph Lowery approaching each other at a black preaching convention, King and Heschel did their own interfaith version of “preacheristic exaggerations” as they marveled at each other’s oratory. Any discrepancies of code, race, or theology that separated a Southern Baptist preacher from an old-world sage descended from Hasidic royalty dissolved in the myriad parallels of prophecy, passion, and poetry.

In keeping with King’s taste for Exodus, the always inventive Heschel observed that the main players at the first conference on race and religion were “Pharaoh and Moses. Moses’ words were, ‘Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, let my people go that they may celebrate a feast unto me.’ …The outcome of that summit meeting has not come to an end. Pharaoh is not ready to capitulate. … In fact, it was easier for the children of Israel to cross the Red Sea than for a Negro to cross certain university campuses.”

If King affirmed “all God’s children,” Heschel asked the world “to remember that humanity as a whole is God’s beloved child. To act in the spirit of race is to sunder; to slash, to dismember the flesh of living community.” Racial prejudice, he said, was blasphemy, “a treacherous denial of the existence of God.”

Echoing James Bevel in Birmingham a few months earlier (“the Bible is now”), King told the audience, “Religion deals not only with the hereafter but also with the here. Here — where the precious lives of men are still sadly disfigured by poverty and hatred. Here — where millions of God’s children are being trampled by the iron feet of oppression.” Heschel said at the same conference, “We think of God in the past tense and refuse to realize that God is always present and never, never past; that God may be more intimately present in slums than in mansions.”

Back in Georgia, did not [Ralph] Abernathy insist “this is God’s Albany”? Heschel pronounced, “This is not a white man’s world. This is not a colored man’s world. It is God’s world.” King argued against resignation to the slights of the world. To those who thought action would be “too little and too late,” that all we can do is weep, Heschel retorted that if Moses had followed that lesson, “I would still be in Egypt building pyramids.”

Both men were capable of intense feelings that required a visceral language to express them adequately. Resorting in his speech to the same imagery of foul smell he had invoked in a Birmingham mass meeting, King said, “The oft-repeated clichés, ‘The time is not ripe, ‘Negroes are not culturally ready,’ are a stench in the nostrils of God.” “My heart is sick,” admitted Heschel, “when I think of the anguish and the sighs, of the quiet tears shed in the nights in the overcrowded dwellings in the slums of our great cities, of the pangs of despair, of the cup of humiliation that is running over.”

To top it all off, both men cited King’s favorite line from Amos, “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an everflowing stream.”

The two men’s friendship had a certain purity. It was forged by the spiritual audacity — the concept is Heschel’s — that each man saw in the other. Such boldness also entailed a distinctive verbal practice. Like King, Heschel understood that the prophetic task entailed “speaking for those who are too weak to plead their own cause. Indeed, the major activity of the prophets was interference, remonstrating about wrongs inflicted on other people,” which in turn entailed talking God into the world.

When King was in need in Selma, he called on Heschel to come to his aid. At a service right before the march, Heschel read Psalm 27, “The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear?” A famous photograph captured the two men walking over Pettus Bridge together. The marchers referred to the bearded sage as “Father Abraham.” Back in New York, Heschel wrote King: “The day we marched together out of Selma was a day of sanctification. That day I hope will never be past to me — that day will continue to be this day.” “For many of use,” he later reflected, “the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”