In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Jeni Stepanek Extended Interview

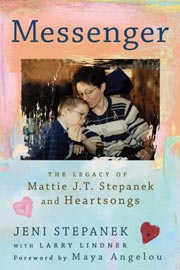

Read and watch Kim Lawton’s interview with Jeni Stepanek, author of MESSENGER: THE LEGACY OF MATTIE J.T. STEPANEK AND HEARTSONGS (Dutton, 2009):

Q: Why was it important to you to tell Mattie’s story now?

There were a couple of reasons. One is Mattie’s been gone for five years now, and in those five years more and more good things have come from his life. We have parks and libraries and school curriculum, school curricula growing, the Just Peace Summit where teens come from all over the world to study his message, and I thought, people are so inspired by Mattie’s writings, by Mattie’s message of hope and peace, I thought it mattered that people know who was the child behind that message, that people know the details of Mattie’s life story, particularly because Mattie believed that he was a messenger, that that was his reason for being. and I knew that if something happened to me, nobody would ever know the truth of Mattie’s story. So that was one goal, was to really lay down the details of Mattie’s life. The other reason that I wanted to tell Mattie’s story is people very often come to me and they say, “I’m so inspired. How could I ever be like this child?” And what I wanted people to know is that he was really an ordinary little boy who made extraordinary choices and that each of us can make those same choices, that each of us can live an extraordinary life regardless of the blessings and burdens that are balanced into each day. And I thought that that mattered to share with people so they could identify with Mattie and—you can’t be Mattie, you can’t raise your child to be Mattie, we can’t ever be another human being, but we can use other human beings as our role models, and I wanted to show how plain and simple my son was. He was as witty as he was wise.

Q: You write in the book about how he really did feel that he was a messenger. In what way? How did he feel that? He really felt it came from God.

Mattie first started telling me when he was about three or four years old that God put messages in his heart, and that his reason for being, that God’s role, God’s plan for him was that he was good with words and that he was to shape words around God’s messages and offer them to other people so that they would hear God’s message as well. Now when your three- and four-year-old says this, I thought it was very sweet, I thought he had some nice things to say, but I couldn’t understand—I didn’t really understand about what he was trying to tell me about God putting messages in his heart, and when he hit about four years old, he began doing things like, in the middle of playing, he would drop to his knees, meditate for two minutes, 10 minutes, and then stand up and say, “I need to write this down. I have a message from God, and I need to put words to it.” And I began to get concerned, actually, and ask him questions like, “Are you hearing voices? Is God’s voice a man’s voice or a woman’s voice? High pitched, low pitched?” I didn’t understand what he was saying, and he looked at me like I had lost my mind, and he said, “Mommy, God’s voice is not like this. It’s a message in my heart, and my job is to give words, to give voice to God’s message.” Mattie spent his entire life saying things like this, and I spoke with priests and rabbis and ministers about this, and I have to admit I don’t think I ever, during his lifetime, fully understood his role as a messenger. I believe he believed that he was a messenger for God. I believed that what he was saying and doing was all good. I could not understand how you could actually hear God’s voice in your heart and use your own words and voice to offer a message to others. I think it’s been more since he died, and the ongoing letters and emails and calls that I get from people who tell me that they remember Mattie from when he was alive, or they’re just learning about Mattie now, and how he continues to inspire them—that is almost like they’re getting a message from God. And I think I’m now beginning to understand that he really—his spirituality and morality were really intertwined, that he did hear messages from God, not in a voice, not in some delusion, but that he was truly inspired with something good, which is God.

Q: What were some of those messages? For people who aren’t familiar with him and his poems, how do you distill the messages?

I think the messages that Mattie offered us from God really fell into two categories, and one could easily be summed up as hope is real, peace is possible, and life is worthy, and he has poem after poem, essay after essay, speech after speech where he discusses, or shares in a literary form, how those look. You know, why hope is real, why it’s not just wearing rose colored glasses or being in denial or turning your head to the truth, that hope begins with an attitude and an attitude is a choice. So I think that’s really one part of the message is all about hope and peace and life, regardless of challenges or the joys in somebody’s life. And then the other side, the other flow of messages that he talked about as coming from God, was what he started calling “heart songs” when he was about 5 years old, and trying to help people understand that we all have a reason for being. Just like you read, or hear, in church God’s plan—Mattie called it our reason for being, our heart song. And the best I can understand it is that it really is the universal truth. It’s what Jesus Christ taught us, it’s what Gandhi taught us, it’s what Martin Luther King teaches us, it’s what any good speaker, any peacemaker teaches us: in giving we shall receive, in doing good, good happens. That doesn’t mean you become rich in money. It doesn’t mean you get miracle after miracle and you live longer. It doesn’t mean that your life is peachy because you’re doing good things, but it means that if you’re open to God being a part of your life, if you can understand your reason for being and offer that to other people, it will come back to you. [It] took me a long time to understand that as well, and I finally came to understand that what he meant by heart song—he told me once when he was about 12 years old, because I said I don’t know what my heart song is, I really, I don’t know my heart song. And he said, “What do you need? What do you want most in life? What do you ache for? What would you do anything to have in your life?” He said that’s the first part of your heart song, because you know why it matters. You’re close to it. If you need money, if you need love, if you need happiness, if you need to be known, you understand why that matters. Your reason for being is to offer that to others. And what Mattie needed and wanted was happiness and love that lead to hope and peace. So he gave that freely to other people through his writings, through his speeches, and in giving other people these messages of hope and peace, that came back to him, and I began to understand that—that is God’s plan for us, to be fully who we were created to be. And what we need we offer it to others, because we get why that matters.

Q: And that’s a spiritual ministry? I think people hear some of the poems and miss the spiritual dimension that seems to be the foundation.

Yes. Now not every poem that he wrote had a spiritual dimension. Some were just pure fun. Some were—people would often ask him to write poetry for an organization or for a specific cause. But the bulk of his poetry, if you really read it carefully, there is a message of hope, of peace, of life, of offering, of finding what’s at your core. When he—I mean one of the most depressing poems I think he ever wrote is called “Abyss,” and it’s when he began really wondering, is my life ending? Am I going to get another miracle? When is my mortality going to end? And he really wasn’t looking forward to death, and he just really felt that he was in a dark space. But in writing about this so people go, “Yeah, I understand and I feel like this,” he said when you’re in this abyss, all you have to do is look up and realize even if you’re at the bottom, there’s the light. You just have to choose what you look at, choose your vision, and once you see it you climb right out. So even when he was struggling, he still would find some way to find inspiration or offer inspiration to other people by identifying with other people’s challenges or sharing his own so that other people could identify with him.

Q: What do you hear from people? You still get letters and emails. What kinds of things do people say, even today?

I get a lot of letters from school children who didn’t think they liked poetry until they started reading Mattie’s material, and then they realized poetry is not something beyond them, it’s not something way intellectual and that you can’t understand, that it’s shaping words in a special way on a page and carefully choosing each word so that it matters. I would say the bulk of what I get is where people say this is how my life has changed because of Mattie, because of what I’ve read, because I saw him on TV, because a friend gave me one of his books. Right now there’s History Associates, a local archive company. They’ve taken 50 boxes from my basement of fan mail and publicity information about Mattie, and they met with me a couple of weeks ago, and they said, “We’ve really tried to sort it, because everybody says they’re inspired.” So they’re trying to say I’m inspired to be a better person, I’m inspired to pray, I’m inspired to be a better parent, I’m inspired to think gentler, to be less judging. They’re trying to now categorize what that inspiration looks like or feels like to different people. I also, especially since it’s been 5 years since he died, get lots, or a fair number, of letters and emails from people who ask questions like when is Mattie going to have a committee for sainthood? What is the prayer I can pray for Mattie, for his cause? I’ve had a dozen or so people ask me for relics. And I go back and I tell people there’s been talk, but there is no formal committee. That doesn’t even begin until year five. But I even get, after he died I got mail from people all over the world that was addressed to “Mattie—Child Poet of America.” Or “St. Mattie—First Child Saint of America,” no other address, and these things would just end up in my mail box which, was very—I mean that’s an overwhelming—it’s beautiful, but the responsibility for me, when I sit back and think my son not only touched lives when he was alive, but since he died, he is continuing to touch lives, to inspire people. It’s the most beautiful thing in the world to have somebody write to you.…

Q: What’s that like as a mother, to know people think your child is a saint?

Well, I’m really careful with that because, one, he’s not recognized as a saint. I mean, if you take a saint as an ordinary person who lived an extraordinary life of holiness and called others to be their best self, absolutely my son is a saint, though not recognized. There are many, many people who are saints though not recognized, and yes, I do hope that one day there is an investigation for his cause, not because that would make me proud, because I think my son could continue being a source of intercession and inspiration for the world, which—that happens more when people are aware of him. So yes, for that reason, I think it would be lovely. But, you know, when I step back and think of me as Mattie’s mom, well, I was the one who would say, “Mattie is your bed made?” And he would say, “Does it look made?” It’s like, well, that wasn’t the question. I was the one that would have to answer his questions of, “If I’m going to be a writer and peacemaker, why do I need trigonometry and chemistry courses?” I saw the little boy, the human side, the child who cried when his feelings were hurt, who was scared of certain things. So I think that’s a blessing for me that I saw the full spectrum of my son. But the responsibility that I feel and the privilege that I feel to think that my son is touching people and touching lives long after my lifetime, long after this generation’s lifetime, is a profound thought that is very humbling, very, very humbling to sit back and think as rough as my life is I would never will or wish my life on anyone else in the world, but how grateful I am that I was chosen to be this child’s mother, that that was part of my reason to be. What a beautiful gift that was that I got to be Mattie’s mom, including the unmade bed. I’m just thrilled about that.

Q: What is that responsibility that you feel?

I think the responsibility is to—part of that was the reason I chose to write this book. I feel the responsibility to share with people the truth of my son’s life. What I don’t want people doing is thinking, “Oh, Mattie,” you know, and putting him up on a pedestal: he’s a little guru, he was perfect, he never got angry, he never got sad, he only spoke bits of wisdom. I mean, he wasn’t—that’s not who Mattie was. So I think the responsibility is for me to share as much information as I can about my son, about his life, so that people do know that he was real. They do know that living a good life doesn’t mean living a perfect life. It means always having God being a part of your life, always, if you have one of those dark moments, that you know instead of saying well, okay, I’m down, I might as well stay here. You pick yourself up, you choose to get out of bed another day. I think it’s my responsibility to offer that information to other people which was kind of hard for me, because I’m more of a private person. Mattie’s an extrovert. I mean he just loved sharing anything and everything with crowds. I’m a little more private, and it was a little more difficult to go out in public to share all the details of our life, but I think when the details of your life can inspire people to find hope when they’re really struggling, or to realize, you know what, I am doing a good job parenting, or despite my burdens I have blessings—whatever the inspiration is that you draw for yourself, for you family, for your coworkers in whatever you’re doing, I feel like it’s my responsibility and my privilege, they’re hand in hand, to share that message—my story, Mattie’s story—and to share those details in a way that brings people closer to him in a very real way—not in a little guru way, but in a very real way.

Q: How has your faith changed in the last five years? How has everything that happened affected your spiritual journey?

I don’t know that my faith has changed dramatically in the last five years. I can say that my faith has grown dramatically across the 20 years that I had with my children, and it’s continued to grow on that spectrum since I’ve buried my fourth and only surviving child, which was Mattie. I think one of the greatest changes I had in faith came during Mattie’s final months. I’m very good at, through prayer, giving God a to-do list, all right? Dear God, this is where I need you, and this is how you can meet my needs. And I give God the little to-do list, and I think I began to realize, towards the end of Mattie’s life, prayer is not just giving God your wishes and your to-do list, it’s asking God to be on my to-do list for the day. It’s asking to bring God into whatever the moments are in my day, so that really started before Mattie died. Since he died, I’ve hit some very, very low points. I think about a year and half after he died, you know, people think if you get through that first year it’s all going to be okay, you get through that first year, and everybody’s there for the first anniversary, because everybody remembers Mattie died. Even my first three children, people are there for the first Christmas, the first birthday, the first anniversary. But then people go back to their everyday life, they go back to their norms, and I can never go back to my everyday life. I can’t go back to my norms because my norm was parenting my children. And it’s not that your life ends, but there’s this dramatic shift. Your path is no longer—you’re still going to end up at the same end point in your life, but you’re taking a totally unplanned path. You’re really starting all over again. I have had mornings where I’m not quite sure what the sane reason is to bother getting out of bed. I always find one, and if I can’t find one, what I’ve learned is to allow other people to give me a sane reason to get out of bed. And I think that’s one of the gifts from God, is that God is present in other people, in my kin family, in my friends. So as sad as some days are, and as much as I miss my children, I really work hard to open my spirit to God’s presence through other people, because I believe my children are with God. I don’t believe that heaven is some place up in the sky, up in a cloud. When people say, oh, Mattie’s right up there, I don’t see that. I see Mattie as right up here. I see spirit and heaven as being wherever there’s goodness, and if that goodness is in a space or in nature or in other people, that goodness is God, and my children are with God. So, you know, I seek to feel what I am looking for, a connection through heaven and goodness, through whatever I can find in the world that’s good. I don’t know if that makes sense or not, but that’s where I am. I’m more praying that God just shows me doors and windows, because I’m really not sure what I’m supposed to be doing in life other than doing good, being my best self. So I ask God to help me recognize any opportunities to do that.

Q: You have an incredible support network. You have some really close people who’ve walked with you from the very beginning. Talk a little more about the role those people have played in your life.

I think if you were to stop and think about the details of Mattie’s life and my life, you think, okay, there’s been financial problems. There’s been a divorce. There’s been four children with disabilities who’ve died. I have a disability that’s progressing every year. You think about those details, and you think, wow, what a horrible life. And since all of my children have died you would look at me and think I’m very much alone. And in all honesty, there are times when I feel alone, because I love my children and miss them. I will never stop mourning the loss of my children, but I also don’t go through each day miserable, because Mattie and I have always had people around us that bring light to our life. In the book you learn more about what Mattie called our “kin family,” and he said you’re related to kin through life, not necessarily blood. It may or may not be blood. But he said blood relations can sometimes be sweet or sour, and kin relations are through life, and life is always good. So Sandy Newcomb is more like a sister to me than a friend, and her three children, who are now adults, two of them with their own children now, they’re like family to me. They’re my kin, and we celebrate holidays and, you know, when one person’s sad we’re all sad, and when one person’s having a moment of joy we all feel joy. I do talk about in the book at one point Mattie asked Sandy, why do you always do such good things for my mom and me? And when Mattie asked her this question he had been in the ICU for about 5 months. At the time Sandy still had two children living at home. She was working two jobs. She herself is divorced and a single parent, and yet she came to the hospital at least three days a week and would spend most of the night there with Mattie so that I could go in the waiting room and take a little break. And she said because that’s all that God asks us to do is to do good for others, to love your neighbor. And she told Mattie that your neighbor is whoever God puts in the path of your life, and if we just all reorganize that and do what we can in the moments that we can, life goes on. Mattie and I have often prayed in gratitude that we have people like that in our lives, that we have such an incredible circle of support. I mean, I’m in two different churches. I’m a Roman Catholic, I love Catholicism. I love the Holy Eucharist. Sandy is Presbyterian. I go with her to her church as well, where I find the most wonderful fellowship, the group of people that are there, just—there are good people everywhere. You just have to be open to that.

Q: You’ve mentioned your speech about not looking at life as how long you live, but how you live. Tell me about that.

One of the speeches that I give is called “Our Dash in Time.” I first heard it in the Presbyterian church from a minister who was talking about the difference between chronos and kairos. Chronos is really a two-dimensional look. It’s a measurement of life in seconds and centuries, whereas your kairos isn’t just seconds and centuries, it’s looking at the depth of the time that you live. So you can look at Mattie’s life, and the dash that marks 1990 to 2004 was not quite 14 years, and you think, what could somebody do in less that 14 years? But because of how Mattie chose to live, because of the kairos of Mattie’s life, the depth of his time, my gosh, I mean he lived an incredibly full life—not just with opportunities to do things, but with how he thought, how he chose to treasure a sunrise, a sunset, a baby holding his finger, I mean, just taking little tiny moments and cherishing them and making them that memorable, that celebrated, and inspiring others to do the same. Not that we don’t want many, many moments in our life; everybody wants to have as many heartbeats as they can. But it really is the measurement of your heart songs, or the depth of your life, that is how we’re going to be remembered. So Mattie, in less than 14 years, is remembered with this powerful legacy, and people smile when they hear his name. It’s sad that he’s gone, and people shake their head at that. But anybody that you say the word “Mattie” to that knows who he is. They smile. That’s powerful. That’s how I want to be remembered, with a smile, not as, oh, that poor woman, she buried her four children, but, wow, that poor woman, she buried her four children, but boy did she love life, and boy those kids were sure happy. I want to be remembered as a smile on people’s faces just like Mattie, and that comes from how you life your life, not how long you live your life.

Q: How are you feeling these days?

Health-wise I have a progressive condition, which is very frustrating. Mattie and I are very resilient, optimistic people. When you have a disease that’s constantly changing, getting worse, you can’t ever just get used to it. You know, we moved into this house a little over three years ago, set it up accessible, and everything was right where I could reach it. Oh, my goodness, a year later, it’s like, well, I can’t reach this anymore, I can’t reach this, so you change things. It’s like, every year, you don’t notice it day to day, but when you go to decorate your Christmas tree or when you go back to the same place, you go to the beach every summer, and you suddenly realize I can’t lift my arm high enough to do this, I can’t transfer independently, you know, out of my wheelchair, I can’t decorate even the closest branch on my Christmas tree anymore. That’s not a lot of fun. Losing the ability to drive, you know, I feel like as I hit middle age, where you have the opportunity to really synthesize academic knowledge and experiential knowledge and spiritual knowledge, and you’re hitting a point where you just feel so blessed with it’s beginning to come together, you actually can do less and less and less physically, and you become dependent on other people, and that’s been really hard for me. And medically I’ve hit a few scares in the last year, with, like, cardiac-type things. It’s kind of scary, but I try as hard as I can to live in each moment and to not think about what’s going to happen. You have to think about what’s going to happen tomorrow, but you can’t focus on that. You have to have a vision for it but not get lost dwelling on it, in the same way with the past you can’t look at the past and get stuck in it in a way that you can’t move forward, and you can’t look at the future and what might happen tomorrow in such a way that you’re afraid to enter it. So I think that’s what Mattie meant with hope. You don’t live in denial, you don’t say the past didn’t happen and the future’s not going to bring its challenges, but you move through it the best you can and have a good attitude. You reflect the moment in a way that God’s there with you.

Q: For a lot of people it’s about control—what you can control and what you can’t.

I’m all about control. I’m an OCD, love control, absolutely, and it’s hard giving that up, you know, and it’s little things, you know. I like cleaning my own house. I like folding my own laundry because I fold in thirds. I’ve learned compulsive people fold in thirds. But now it’s I’m so grateful for anybody that does my laundry I don’t care if it’s folded in quarters or halves or thirds or fifths. I’m happy that people are doing it. But it’s really hard letting go of that control. It’s really hard knowing I will always be the passenger in a car. I will never be driving again. That’s a really, really tough thing when I’m a doer, a giver, a be-er, and you have to be the recipient and call someone and ask them to do something for you. That’s a tough lesson for me.

Q: What are you doing professionally these days?

I would say I’m an advocate and a consultant, a motivational speaker. I love writing, speaking, doing research, and the fields that I work with range from education, health care and family-centered care collaboration, but also peace and hope. I do a lot of mentoring of teenagers around the world who want to understand, how is peace possible? And I help people understand Mattie’s premises. Mattie called it the three choices for peace. What are these choices, how can we embrace them—that peace is not just an absence of violence, peace is also a conversation with people you don’t know or don’t understand. Peace is taking care of the earth. Just helping people understand how basic needs, equitably meeting basic needs of people, leads to peace. So my speeches are everything from how to work with families whose children might be dying to why does it matter that people feel happiness, hope, and have food and water and education? How does that lead to peace? And I love the work that I do.

Q: And the Mattie J.T. Stepanek Foundation?

After Mattie died, people that are in my neighborhood, in the city of Rockville [Maryland] in the King Farm community, they said Mattie’s message is not one that we want to get lost with the fact that he died barely a teenager. Had Mattie been [in his] 30s or 40s when he died, there’s a chance that he would have had an automatic place in history, and there were people who knew Mattie as a person, and part of the reason that I said I wrote this book—that he wasn’t a guru, he was witty and wise, he was very real. So people who were his neighbors said we need to make sure people understand who Mattie was, what was his message. So they started the Mattie Stepanek Foundation, and really the mission of our foundation is to make Mattie’s message available and accessible, accessible meaning understandable. So we are working on curriculum guides so that teachers who want to incorporate peace or poetry or character development into preschool, into high school, into a university course, that there’s different worksheets or presentations, videos that they could rely on to introduce anything from “Heartsongs” to the three choices for peace to their students, and there are actually schools around the country who are already doing this type of work, and we’re trying to help incorporate what they’re doing with what we are doing. But it’s really just keeping that message of hope and peace out there and alive, and I think what we believe the foundation is, is that Mattie’s message is not unique. He offered us the universal message, you know: Give and you shall receive. Mattie’s life was unique. Mattie’s experiences were unique. Mattie’s choices as a young child were unique. So as a messenger he’s very powerful, you know. People listen when they hear Mattie’s words either on a page or on TV or even in the park named after him, the sound bites you can listen to. So because of that the message is the same thing other people say, but as a messenger he’s very unique, and people are drawn to him for any number of reasons. So it’s to keep that available for people, and I’m proud to be the eternal chair of this foundation.

Q: Other people say they have sensed Mattie. Have you?

I have had people who have contacted me to say they believe Mattie has interceded in their lives. They believe that Mattie has healed their child or touched their spirit or turned them back to God or prevented them from suicide. I have gotten messages; some of the messages I think are very profound and very believable. Some I think are people who want to feel something good. I personally have not felt my son, I would love to feel him, but I think if—I think my son, if he is speaking into people’s hearts or spirits, if he is interceding in people’s lives, and people recognize it…things like that are very powerful for me to hear, and what I would give to have my son come and stand and just say hi or yo, just say anything, just touch me, but I know that that would be wrong, and I think that my son is wiser than that, because if my son came and spoke to me or touched me, and I knew without doubt this is my son, I so miss him that I’m afraid I’d never emotionally or physically be able to move from that spot. I would be trapped, thinking OK, if he could do it once, this must be the magic portal. I’m going to stay right here, and I find that the people who tell me they have received some message from Mattie are ones that are able to move on after that. Those are the ones I believe more….

Before Mattie died, in the final week of his life, I mean, Mattie knew he was dying and I did, too. But a parent can never, ever just say, OK, it’s time, you can go. I mean, that’s a really tough thing, even as your child is dying in front of your eyes and your heart. You can’t give them permission. You can’t be OK with it. You can give them permission, but you can’t really be OK because that goes against everything that parenting is. It’s not okay to bury a child, it’s not OK. No matter how good a life that child lived, no matter how graceful the death is, the death of a child—nothing makes it right. So Mattie was clearly ready to go but wanted me to be, he wanted me to let him know that I’d be OK, and he had said things that he had said to other people before: you can’t lie down in the ashes of another person’s life. He had said all kinds of profound things: Take my message forward. Your message, my message are so similar, Mom, be a messenger for me. You know, take the torch, give more light to your own message, beautiful things. I think the thought that was most meaningful, and if I ever write about my life story about grief—because this book is not my story, it’s Mattie’s story. It’s not my story of loss. It’s his story of life—if I ever wrote my own story it would be called “Choosing to Inhale,” because that was the challenge my son gave me. He said when I’m gone, promise me you will choose to inhale, not breathe merely to exist, and that means finding some worthy reason to move into each next moment, and that’s the most difficult choice I face every single day, but it’s the most worthy choice. Once I’ve made that choice to move forward, to move with God, to be a messenger, to give a speech, to write a book, to serve as a consultant, all the different things I do, I have to choose that, because the easiest thing to do would be to lay in bed until it’s my time to be with my son again. But he challenged me to make life more than breathing. Choose to inhale.

I had four children in a four-and-a-half year time span, which makes me a very firm, good Irish Catholic woman, which is what I am. But when I was having these children, I did not know I was going to give birth to children with this condition. When I was having children, I was apparently healthy, active, running two to five miles a day, coaching and playing sports, working on my first doctoral degree, had no clue—and it was clear something was wrong with the children, but they were misdiagnosed, and with the misdiagnoses came the misprognoses of recurrence. So I thought the first one was a fluke of nature, the second one was recessive, you know, they told me the third one would be healthy. Mattie’s my fourth. I had, I mean, I was doing, practicing many ways not to have a fourth. He was clearly a spirit meant to be, not an accident, a spirit meant to be. So yes, by the time Mattie was born I had already buried two children and had a third that was going to die from the same condition, and I knew that Mattie, short of a miracle, was going to have this mystery ailment that afflicted my children. We found out when Mattie was two what was wrong with me, and that’s when they went back and backtracked and figured out what was wrong with the kids, and I had no more children after that. What kept me going through all of that—while one of my children was alive, what keeps you going is very different than what keeps me going now. When your child’s alive, your number one focus is keep that child alive, and if the child’s not in an active medical crisis, then make that child know life is good despite the equipment, despite the ventilator, the trach, the needles, being in the hospital. Why would you want to celebrate life? Why would you want to live longer? So how I coped during the bulk of the 20 years when I had my children was by teaching them that life is a celebration….I gave my children a celebration of life in whatever few months or years they had. So even though you grieve the loss of your child, when there’s still another living child, not that the grief isn’t there, but you have to focus on celebrating life with that child, with the one that’s still alive. You can’t give them your grief just because you miss their sibling. When Mattie died, that’s when the grief became so overwhelming, because where do you put your mommy role? It’s really difficult to be a mommy to children who have died. You know, bringing flowers to their grave, cutting the grass around their marker, that’s—it’s a very unnatural role, but you don’t suddenly not feel like you’re a mommy any more. You want to nurture, you want to take care of things, and you want to teach somebody to celebrate life. So while my children were alive, clearly I coped, you know, through religion, through faith, through spirituality, but also I had my children. That was my celebration. It’s a very different thing once there is no child there, and you really are relying on God, your spirituality, and the kin family of support that’s around you to help you choose to inhale everyday.

Mattie knew his entire life that he had a condition that could lead to early death, that he had a life-threatening condition. When he was 10 years old, he realized that that possibility of an early death was becoming more of a probability. We really thought he was going to die before his 11th birthday. We’re not quite sure how he eked out those last three years. We’re thrilled that he did. I think it was when Mattie was 13, it was the fall of 2003, Mattie had several conversations with me where he said, “God’s no longer giving me messages. God’s just walking with me through my life,” and at that point he realized his time on earth was complete and that he would probably die sometime during the coming year because he had fulfilled his reason to be. And he was not excited about that. He really wanted God to say you’ve done such a good job I’m going to give you five bonus years. I mean, he was not anxious to die. But I think he realized when he was 13, I’ve done what I came to do. I’ve done it well. There was a sense of urgency that he felt to get as much in place as possible that could go on after him. He called it his echo and his silhouette. You know, get as much writing down; get as many video tapes in so that things would last. So he always knew that he would die soon. I think at 13, I think on the day that he turned 13 he knew he was not going to turn 14. He was very clear. He tried to tell me spring of 2004 before he went into cardiac arrest. He kept trying to prepare me for what was about to come, and I couldn’t listen to him. I just—I couldn’t. I knew what he wanted to say, and I thought, if I listen to you I’m going to tell you, it’s almost like saying, OK, all right, and I couldn’t do it, and I feel very badly about that now. I feel like I didn’t—it was one of my mommy decisions that I regret. You know, I should’ve just put my arm around him and said that must be really difficult, you must feel very alone. But I thought if I did that he’d think I’m saying, wow, this is really sad but it’s—you’re right. So I wouldn’t even let him talk to me about it. I just—I couldn’t tend to it, and I feel very badly. I will forever feel badly about that. But I don’t think he holds that against me, I think he knew that I was being a mommy.