Poetry and the American Religion

by David E. Anderson

It makes sense that the Library of America, a nonprofit publisher dedicated to printing authoritative editions of America’s most significant writings, would bring out an anthology of American religious poetry. After all, it has already done excellent two-volume collections of both 19th- and 20th-century poetry, as well as acclaimed volumes by Whitman, Stevens, Frost, and Pound, and in 1999 it published a worthy and well-received collection of American sermons.

For the most part, AMERICAN RELIGIOUS POEMS follows in that esteemed tradition. The anthology contains works by more than 200 poets, from the Colonial-era Bay Psalm Book (represented by Psalm 19) and the Puritan Thomas Dudley (1576-1653) to Korean-American Suji Kwock Kim (b. 1968) and Wheaton College English professor Brett Foster (b. 1973). In addition, editors Harold Bloom and Jesse Zuba, reflecting the ambiguous place of American Indians and African Americans in the nation’s cultural history, include two separate sections — one of American Indian songs and chants and the other a brief collection of spirituals and anonymous hymns.

There is the usual apparatus of an index of poets, titles, and first lines, as well as a short set of brief notes explaining potentially difficult or obscure references in the poems. A note on Michael S. Harper’s reference to “the demonic angel, Elvin, / answering my prayers on African drum” in his poem “Peace on Earth” explains that it is an allusion to Elvin Jones, the jazz drummer who played with John Coltrane. Another tells the reader that the title of Hart Crane’s “Lachrymae Christi” can be translated “Tears of Christ.”

More unusual is a reader’s guide that gives brief definitions and descriptions of topics in some of the poems — Apocalypse, Being, Nature, Praise, Prayer, The Spiritual Quest, and so on. Thus, under Apocalypse, Robert Frost in his “Once by the Pacific” is understood to see “apocalyptic energies at work in an ominous coastal landscape, though the invocation of the world’s end that closes the poem, with the word of God cast in the American vernacular, is as much playful as prophetic.”

All anthologies of necessity mirror the taste of their editor, or, in this case, editors. Reflecting perhaps ego or renown, the volume is called “An Anthology by Harold Bloom,” but both Bloom and Zuba are listed as editors. There is no indication of the division of labor, and each contributes an introduction — in Zuba’s case, a conventional and useful essay that explains some of the guiding principles at work in the selections, for indeed there is much fine poetry here, a great deal of it by lesser known poets.

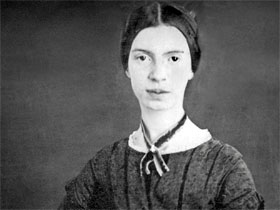

It is always, given space limitations, a tough choice whether to include two or three poems by a single poet, thus limiting the number of poets represented, or to let a larger number poets have their say with a single poem. On the whole, the anthology strikes a generally fine balance. It is nice to see a generous representation (10 entries) of the 18th-century devotional poet Edward Taylor, but to my mind a dozen poems by Emily Dickinson is excessive. In the 20th century, A.R. Ammons with a half-dozen poems (why is the self-serving poem titled “For Harold Bloom” among them, except that Bloom identifies “the Whitmanian” Ammons as “my close friend”?), and Lucile Clifton, lovely as her work is, are both overrepresented, while the paucity of Robert Lowell (only a single poem), as well as the absence of Daniel Berrigan, Adrienne Rich, Jack Kerouac, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, are near unforgivable.

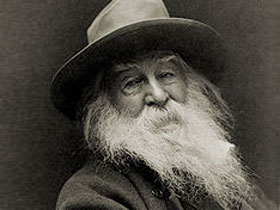

More unfortunate is Bloom’s introduction, made up of equal parts bombast and muddle, obfuscation and plain silliness (“Being a god is rather hard work”), as well as irrelevant political asides (“Emerson, opposing the admission of Texas to the Union, rightly prophesized that Texas would destroy America, though President Bush II goes beyond even Emersonian admonition”). Is Bloom’s view of Whitman bombast or silliness: “He is American religious poetry, and he himself is a Christ rather than a Christian.” Presumably, Bloom’s introduction is an effort to establish a justification for the poetry that follows, a theory about religion in America that he finds expressed in one part of a poetic tradition that runs from Whitman through Crane to Ammons and Ashbery.

Bloom, who eschews history, seems either not to understand or to willfully misread American religious history. He grasps neither its diversity nor its main currents. Nor does he seem to know or care about religion as it is experienced by most Americans, Christian or not, including many of the contemporary poets — say a Samuel Hazo, Mary Oliver, or Paul Mariani — included in his anthology. For Bloom, the two hundred years prior to Emerson do not exist, but he cannot even get Emerson right.

Bloom’s Emerson appears to be the inventor of a uniquely American creedless religion — “the American Religion” — in which Whitman is sometimes Adam, sometimes Christ, sometimes a version of Yahweh. “What is the center of Whitmanian religion? Clearly, it is Walt Whitman himself as Divine, post-Christian yet a messiah, another son of a carpenter who is also a son of God.” It really is a version of the myth of the American Adam, which R.W.B. Lewis so skillfully explored and skewered in his 1955 book, THE AMERICAN ADAM: INNOCENCE, TRAGEDY AND TRADITION IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY.

The myth — of America as Eden, the American as Adam inventing a new world with no ties or connection to the Old World — flourished among one strata of influential American intellectuals in mid-century America before the Civil War. But Emerson did not spring fully formed from the soil around Concord, Massachusetts. His American Religion — and Whitman’s, too — owes much to British and European Romanticism, evolving Unitarianism, Transcendentalism, and pantheism, not to mention concepts from Hinduism and Buddhism, such as Brahma and karma, that were also part of the cultural and intellectual milieu, as the late Yale historian Sydney Ahlstrom (whom Bloom also quotes on Emerson without recognizing the wider context) pointed out in his classic text, A RELIGIOUS HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE.

Indeed, Bloom seems to be so anxious to turn the Whitman-Dickinson-Crane tradition into a religion (“Dickinson, like Whitman, is a major poet of the American Religion, but she does not assume the role of American Christ as Whitman did” and “Crane’s still undervalued American epic ‘The Bridge’ celebrates what I again would call the American Religion”) that he ignores religion and the many religious sensibilities that have marked the nation’s remarkable religious history. Apart from Emerson, the only references he makes to actual American religious history are to the Second Great Awakening, when he quotes a letter of Dickinson seemingly distancing herself from its emotionalism; Whitman’s recollection of Quaker preacher Elias Hicks; and the Cane Ridge Revival of 1801.

Bloom misreads Cane Ridge as badly as he does Emerson, calling it a fusion of Gnosticism, Orphism, and Enthusiasm, which would certainly be a surprise to all those evangelical, Bible-believing Protestants spawned by its remarkable events. It is worth quoting Ahlstrom here: “The most important fact about Cane Ridge is that it was an unforgettable revival of revivalism, at a strategic time and a place where it could become both a symbol and impetus for the century-long process by which the greater part of American evangelical Protestantism became ‘revivalized.’ A second consequence of this historic camp meeting and the great revival which swept across Kentucky, Tennessee, and southern Ohio during the next three years was the vitality which it poured into the participating churches. The future of the country’s denominational expansion was in large part determined by the foundations laid during this period.” While Cane Ridge may have manifested Enthusiasm, the religion of the revival was neither Gnostic nor Orphic, and it had little in common with either Bloom’s American Religion or the mainstream poetic tradition.

Bloom’s little essay leaves one scratching one’s head, asking either “What does this mean?” or “So what?” or sometimes both. To say, as Bloom does, that “so pervasive is the American Religion that it makes obsolete most distinctions between theism, agnosticism and atheism” is to say, finally, that language doesn’t count, that it points to nothing. At the same time, while Bloom dismisses traditional religion, especially Christianity with its Middle Eastern and European origins and expressions, he wants to garb his American Religion with all the trappings of Trinitarian Christianity. Thus, the non-American D.H. Lawrence is not Whitman’s John the Baptist but his St. Paul. The Exodus is the thematic center of American religious poetry. “The American Jesus, the American God, the American Holy Ghost: these have only spectral traces of European and Middle Eastern dogma.” What we have in Bloom’s American Religion is a version of faux Christianity.

But no matter. His redundant introduction can be safely skipped for the more sensible and usable one by Jesse Zuba. Better yet, the poems themselves, despite some glaring lapses, offer the best antidote to Bloom’s bluster and demonstrate the host of religious sensibilities American poets bring to their work. As the poet Samuel Hazo, who compiled a brief volume of contemporary religious poetry in 1963, said of the poems he gathered, they are “testaments of how poets have tried to discover themselves in the world around them, and the world around them in themselves. This is ultimately every poet’s mission, and it is a spiritual or religious mission.”

David E. Anderson is senior editor of Religion News Service. He has also written for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on the novels AFTER THIS by Alice McDermott and GILEAD by Marilynne Robinson.