The Poetry of Christmas

by David E. Anderson

Christmas, more than any other holiday in the Christian calendar, seems to spark the poetic impulse — an impulse that began, as the Episcopal priest, professor, and poet Chad Walsh (1914-1991) remarked some years ago, with the heavenly host and their proclamation: “Glory to God in the highest, And on earth, peace, good will to men.” (Luke 2:14, KJV)

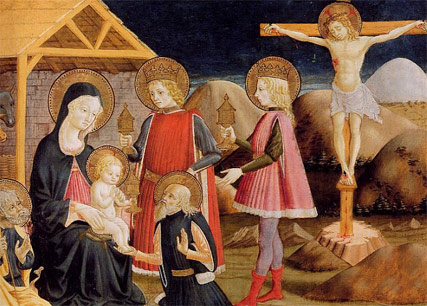

Since then, as Christmas and its stories and legends have increasingly grasped the imagination of believer and nonbeliever alike, the festival has inspired countless poems and carols and songs. Some, of course, have been seasonal and secular, but most are religious, focusing in different ways on the Nativity and the related observance of Epiphany, the journey of the three kings and their arrival at the manger on the 12th day of Christmas.

Although Christmas was not a major celebration in the early church, “Hymn on the Nativity IV,” one in a series of early Syriac poems by Ephrem (d. 373), a deacon of the church in Asia, has survived, and it points to the paradoxes, reversals, and symbolism that became an important part of Christmas poetry:

Mary bore a mute Babe

Though in Him were hidden all our tongues.

Joseph carried Him, yet hidden in Him was

A silent nature older than everything.

The Lofty One became like a little child, yet hidden in Him was

A treasure of Wisdom that suffices for all.

He was lofty but he sucked Mary’s milk,

And from His blessing all creation sucks,

He is the Living Breast of living breath;

By His life the dead were suckled, and they revived.

(from DIVINE INSPIRATION: THE LIFE OF JESUS IN WORLD POETRY, edited by Robert Atwan, George Dardess, and Peggy Rosenthal, Oxford University Press)

Ephrem’s liturgical poem nicely captures the essential metaphor of the Nativity and the bedrock Christian affirmation that in a very human and humble birth, God — the Lofty One — is present in the world. Ephrem takes hold of the contrasts and apparent contradictions that mark this melding of humanity and divinity: a mute babe is also the Word (“all our tongues”). The infant’s humanity is stressed in the fatherly touch of Joseph carrying him, but hidden in the human is his eternal existence with God — “a silent nature older than everything.” Ephrem seems to delight in spinning out the paradoxes — the innocent little child holds “a treasure of Wisdom”; the baby takes nourishment at Mary’s breast but gives nourishment to all creation as “the Living Breast of living breath”; and ultimately the paradox of life and death, for in the babe’s life death itself is overcome.

All of these metaphor-like yoked contrasts — divinity and humanity, life and death, power and powerlessness, innocence and wisdom — are sparely yet suggestively and powerfully grounded in Luke’s and Matthew’s birth narratives, where the rude manger is accompanied by heavenly hosts, Mary’s hymn is that the poor are lifted up and the rich are sent away hungry, and the Magi, symbols of both power and wisdom, pay homage to, as Ephrem has it, “a mute babe.” It is just these paradoxes that worked and continue to work their power on poets.

As the observance of Christmas began to grow slowly in the church — the term “Cristes maesse” appears as early as 1123 in Old English and as “Christmas” by 1568 — and also to become a part of the broader culture — “so hallowed and so gracious is the time,” Shakespeare says of the holiday in “Hamlet” — so too did the body of Christmas poetry swell. In the English tradition, it continued to mine the biblical narrative’s apparent paradoxes of weak and powerful, rich and poor, innocence and guilt. A good example is “The Nativity of Christ” by the Jesuit poet Robert Southwell (1561-1595):

Behold the father is his daughter’s son,

The bird that built the nest is hatched therein,

The old of years an hour hath not outrun,

Eternal life to live doth now begin,

The Word is dumb, the mirth of heaven doth weep,

Might feeble is, and force doth faintly creep.

O dying souls, behold your living spring;

O dazzled eyes, behold your sun of grace;

Dull ears, attend what word this Word doth bring;

Up, heavy hearts, with joy your joy embrace.

From death, from dark, from deafness, from despairs,

This life, this light, this Word, this joy repairs.

Gift better than himself God doth not know;

Gift better than his God no man can see.

This gift doth here the giver given bestow;

Gift to this gift let each receiver be.

God is my gift, himself he freely gave me;

God’s gift am I, and none but God shall have me.

Man altered was by sin from man to beast;

Beast’s food is hay, hay is all mortal flesh.

Now God is flesh and lies in manger pressed

As hay, the brutest sinner to refresh.

O happy field wherein this fodder grew,

Whose taste doth us from beasts to men renew.

By the 17th century, Robert Herrick (1591-1674), an Anglican priest, could easily write about both the sacred and secular aspects of what was becoming a holiday season in addition to a Christian festival. In “To His Saviour, a Child; A Present, by a Child,” Herrick sounds what has become a major theme in Christmas poetry and song: the conjoining of Christmas as a celebration for children and as a festival about the child. Herrick’s poem implicitly asks the reader to come to Christ as a child, to recover the childlike sense of awe and wonder at the birth. It anticipates the popular song “The Little Drummer Boy,” written in 1958 by Harry Simeone (with Katherine Davis and Henry Onorati), in which a poor shepherd boy, with a drum instead of Herrick’s whistle, comes to visit the newborn babe with even less that a flower to present to the Christ child.

Go prettie child, and beare this Flower

Unto thy little Saviour;

And tell Him, by that Bud now blown,

He is the Rose of Sharon known:

When thou has said so, stick it there

Upon his Bibb or Stomacher:

And tell Him (for good handsell too)

That thou has brought a Whistle new,

Made of a clean strait oaten reed,

To charm his cries (at times of need):

Tell Him, for Corall, thou hast none;

But if thou hadst, He sho’d have one;

But poore thou art, and knowne to be

Even as monilesse as He.

Lastly, if thou canst win a kisse

From those mellifluous lips of his;

Then never take a second on,

To spoile the first impression.

Herrick, however, could also write a verse that celebrates the “eat, drink, and be merry” secularization of the season that so appalled some English and American Puritans and their ideological descendants:

Come, bring with a noise,

My merrie, merrie boyes

The Christmas hog to the firing;

While my good Dame,

She bids ye all be free;

And drink to your hearts desiring.

But Christmas poetry has also served as a critique of the times in general. Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) showed the way in these quatrains from his “In Memoriam”:

The time draws near the birth of Christ

The moon is hid; the night is still;

The Christmas bells from hill to hill

Answer each other in the mist.

—-

Ring out a slowly dying cause.

And ancient forms of party strife;

Ring in the nobler modes of life,

With sweeter manners, purer laws.

Ring out the want, the care, the sin

The faithless coldness of the times;

Ring out, ring out my mournful rhymes,

But ring the fuller minstrel in.

Tennyson, of course, was, for better or worse, the voice of Victorian England (Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901). “In Memoriam” was written in 1850, as the era was beginning to flourish and its pressures and cultural contradictions were beginning to be felt. An economic middle class was emerging, and it was shaped by a belief in human progress made possible by new scientific advances (Darwin’s THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES would be published less than a decade after Tennyson’s poem). But that belief in progress was also fueling doubt and undermining religious faith. The change would be most powerfully captured by Tennyson’s younger contemporary Matthew Arnold in “Dover Beach” (1867), where the poet can only hear “the melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the retreating Sea of Faith.

It was the Victorians who created the modern Christmas, with its attendant nostalgia for a past, a certainty that never was, and a sentimentality, compassion, and empathy for others that seemed to glow in Victorian reconstructions. They sought to pose this holiday against the hypocrisy and avariciousness, the doubt and bafflement, of their time. Contemporaries read “In Memoriam” both as a judgment on their own time and as a message of hope and reassurance that might stay the erosion of their diminished Christian faith. It seems that Tennyson’s own faith was a little sketchy, but T. S. Eliot admired the poem for what he called “the quality of its doubt” and found it to be a work of despair, but “despair of a religious kind.” Both readings are possible, as Christmas offers hope, however uncertain, while also standing in judgment on the present age.

American poet Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962) seems to pose an idealized past against the strife-torn present of World War II in his 1941 poem “Two Christmas Cards,” but there is also, in the third stanza, the hook of the Christmas paradox. Here, however, the reversal is reversed. The contrast of the dark present with the innocent babe of the Nativity is stood on its head. Any turning away from wars and confusions to a time that was “simple and gay” is a nostalgic illusion that Christmas refuses to enact. It is almost as if Jeffers is standing the Victorian longing of his childhood on its head. As Hitler and Hirohito share the world now, Caesar and Herod did then. “Dark though our day,” Jeffers says, dark too was that first Christmas day. Any hope — the light snow, the kneeling ox — will have to be wrested from the darkness.

For an hour on Christmas eve

And again on the holy day,

Seek the magic of past time,

From this present turn away.

Dark though our day,

Light lies the snow on the hawthorn hedges

And the ox knelt down at midnight.

Only an hour, only an hour

From wars and confusions turn away

To the islands of old time

When the world was simple and gay,

Or so we say,

And light lay the snow on the green holly,

The tall oxen knelt at midnight.

Caesar and Herod shared the world

Sorrow over Bethlehem lay,

Iron the empire, brutal the time

Dark was that first Christmas day,

Light lay the snow on mistletoe berries

And the ox knelt down at midnight.

(from BE ANGRY AT THE SUN, Random House)

The San Francisco poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, often associated with the Beat Generation, could be sharply, almost savagely critical of the commercialization of Christmas, as in this verse from “Christ Climbed Down”:

Christ climbed down

from His bare Tree

this year

and ran away to where

no fat handshaking stranger

in a red flannel suit

and a fake white beard

went around passing himself off

as some sort of North Pole saint

crossing the desert to Bethlehem

Pennsylvania

in a Volkswagen sled

drawn by rollicking Adirondack reindeer

with German names

and bearing sacks of Humble Gifts

from Saks Fifth Avenue

for everybody’s imagined Christ child

(from A CONEY ISLAND OF THE MIND, New Directions)

But perhaps no one has captured the paradoxical reversals implied in the Nativity narrative as well as T. S. Eliot. In his “Journey of the Magi,” Eliot has one of the three wise men, years later, recalling the difficult journey to the manger — “a cold coming” with “the ways deep and the weather sharp”:

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Eliot’s connection of birth and death can be read as a gloss on the believer’s death and new life in Jesus — a connection between the incarnation and the crucifixion made explicit in W. H. Auden’s “For the Time Being,” a Christmas oratorio, composed between October 1941 and July 1942. In this powerful modernist rendering of Christmas as it is experienced by contemporary Christians, Auden combines the ordinary details of everyday life with the larger doctrines of Christianity.

The long poem, a play-like dramatic composition intended for voice and orchestra but without costumes, scenery, or dramatic actions, follows the Christmas story from Advent through the birth and the flight into Egypt with characters and voices such as the shepherds, Mary, Joseph, and a narrator. Auden plays the biblical narrative off contemporary, conversational speech. He wants to set the wonder and the horror (the slaughter of the innocents) — the awesomeness of the narrative — within the bland ordinariness of contemporary life as its own paradox. In the passage below, Auden is bringing his story to a close in a conversational soliloquy by the narrator: “Well, so that is that. Now we must dismantle the tree.” The matter-of-factness contrasts sharply with what might be glibly called the “true meaning” of Christmas, but it also undermines that “meaning” as well: “we have seen the actual Vision and failed / To do more than entertain it as an agreeable possibility.” But even so, Auden says, seeing the “actual Vision” diminishes rather than enriches contemporary life. “To those who have seen the Child, however dimly, however incredulously / The Time Being is, in a sense, the most trying time of all.” It is, as he hints in the references to Lent and Good Friday, the ultimate paradox and mystery of Christmas: that in the ancient birth the believer, like Eliot’s Magi, experiences a contemporary death — “the most trying time of all” — in order to live a new life.

Well, so that is that. Now we must dismantle the tree,

Putting the decorations back into their cardboard boxes —

Some have got broken — and carrying them up to the attic.

The holly and the mistletoe must be taken down and burnt,

And the children got ready for school. There are enough

Left-overs to do, warmed-up, for the rest of the week —

Not that we have much appetite, having drunk such a lot,

Stayed up so late, attempted — quite unsuccessfully —

To love all of our relatives, and in general

Grossly overestimated our powers. Once again

As in previous years we have seen the actual Vision and failed

To do more than entertain it as an agreeable

Possibility, once again we have sent Him away,

Begging though to remain His disobedient servant,

The promising child who cannot keep His word for long.

The Christmas Feast is already a fading memory,

And already the mind begins to be vaguely aware

Of an unpleasant whiff of apprehension at the thought

Of Lent and Good Friday which cannot, after all, now

Be very far off. …

(from COLLECTED POEMS, Vintage International)

For poets, those fleeting images in Matthew and Luke have spawned a host of visions, sometimes comforting, sometimes uncomfortable, that have allowed them to plumb the depth of belief, to challenge their times, and to play — in the best sense of that word — with the central mysteries of the Christian faith.

David E. Anderson is senior editor at Religion News Service.