In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Eradicating a Global Scourge

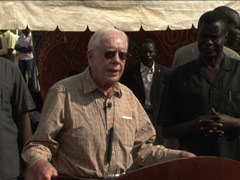

FRED DE SAM LAZARO, correspondent: The trademark smile is undiminished by the years or by a long, punishing journey to this remote village in Southern Sudan, a grateful community, said the area’s Anglican bishop.

BISHOP MICAH LEILA DAWIDI: I want to thank you for having been courageous to come and bear with us all the suffering of our people.

DE SAM LAZARO: Jimmy Carter is in the final stretch of a global campaign he’s led to eradicate a tropical disease called Guinea worm.

JIMMY CARTER: The bishop has described the travels of the chosen people out of slavery in Egypt and into the Promised Land and the fact that they prayed and worked hard and had faith and God gave them water.

DE SAM LAZARO: Similarly, the former president said, the world will soon be delivered from a scourge that dates back to biblical times. His methods and approach have been praised as an effective model for how to tackle entrenched poverty and disease.

CARTER: We’ve been working on it now for more than 20 years. We’ve reduced the incidence from more than two-and-a-half-million cases down to about 2500 cases in the whole world, and the last major holdout will be here in Southern Sudan.

DE SAM LAZARO: In war-torn Southern Sudan, clean water is a rarity for many people, and of all the diseases from unsafe water few are more disabling than Guinea worm.

DE SAM LAZARO: Worm larvae enter the body and grow up to three feet, crippling the human host. The only cure is to slowly, painfully extract the parasite as it emerges through skin blisters. To relieve the burning pain, patients dip these blisters in water, typically open ponds, and that’s when the worm spreads new larvae, and that starts the whole cycle again.

CARTER: There’s no question about it that we’ll be free of this plague throughout Southern Sudan if the people remain to have their faith and also work hard to make sure that no one with Guinea worm ever goes into a pond where you get water from the pond. It’s very important that you not let them go into a source of drinking water, because they spread the disease from themselves to many others.

CARTER: There’s no question about it that we’ll be free of this plague throughout Southern Sudan if the people remain to have their faith and also work hard to make sure that no one with Guinea worm ever goes into a pond where you get water from the pond. It’s very important that you not let them go into a source of drinking water, because they spread the disease from themselves to many others.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Atlanta-based Carter Center has trained thousands of field workers and volunteers. They’ve taught how Guinea worm is spread and distributed simple tools to prevent it: a personal filter used like a drinking straw or a treated cloth which can keep the parasite out of water people gather from ponds. Today, field workers like Simon Taban are tracking down some of the last cases, trying to protect ponds to contain the spread of the larvae and break the transmission of the worm.

How has this campaign succeeded unlike so many aid projects in the developing world? The epidemiologist in charge pays much credit to Jimmy Carter. He’s motivated by faith but does not proselytize. He’s opened doors and raised some $225 million for the cause. Most critical, the Carter Center approach is not prescriptive or top-down, but respectful and collaborative, says Dr. Don Hopkins.

DON HOPKINS, M.D. (Epidemiologist, Carter Center): People are very, very astute at picking up condescension, and unfortunately there’s a lot of that, especially with Westerners coming into the countries, and I think you have to approach people with the idea that ‘we’re here to help you and no, we don’t have all the answers. You know your own community far better than we ever will, but here’s this information. Use it to help yourself get rid of this disease.

DE SAM LAZARO: As one example, former President Carter says they’ve used local religious beliefs to reinforce what science calls for. For instance, some communities didn’t like the idea of spraying ponds with chemicals to kill the guinea worm larvae.

DE SAM LAZARO: As one example, former President Carter says they’ve used local religious beliefs to reinforce what science calls for. For instance, some communities didn’t like the idea of spraying ponds with chemicals to kill the guinea worm larvae.

CARTER: In fact, their ponds of water were looked upon as sacred. If that particular rain-filled pond hadn’t been there, they wouldn’t have existed. They wouldn’t be alive. Of course, we said that the pond was in fact sacred, but there was a curse on that pond, and if they would just help us remove those Guinea worm eggs from their pond or from the drink of water that they took out of that pond, then that curse could be removed from their pond and their village forever. So we had, you might say, a not only philosophical but also a theological explanation to make.

DE SAM LAZARO: They’ve also had to deal with the political realities, and here, Dr. Hopkins says, having a former head of state personally involved helped smooth out many complications.

HOPKINS: He’s always willing and available to call, to write, physically meet with heads of state. The protocol really doesn’t allow him to write directly to a minister of health. I can write to a minister of health, but when he comes in at that level it helps enormously. He’s also been very helpful in having that same kind of approach to leaders of international agencies, the WHO, UNICEF, various donor agencies as well.

CARTER: We have to recognize and acknowledge that corruption exists in many parts of the world still. Not just in Africa but in many countries, even some developed countries as well.

CARTER: We have to recognize and acknowledge that corruption exists in many parts of the world still. Not just in Africa but in many countries, even some developed countries as well.

DE SAM LAZARO: The former president said the Carter Center works directly at the local level to treat people and to break the transmission of Guinea worm, bypassing governments plagued by corruption without offending them.

CARTER: Some of the ministers of health in African countries, for instance, obtain their positions as a minister just because they were heroic fighters in winning freedom from the colonial powers in Europe. So we honor them, but we don’t ever derogate or condemn them, even when we know corruption exists, and we don’t let them impede the Carter Center’s policy of going directly into the jungles and into the desert areas, directly to the villages where we know the disease needs to be eradicated.

DE SAM LAZARO: He says his work in public health—focusing on Guinea worm and other neglected tropical diseases—was inspired by his late mother, Lillian Carter, about whom he wrote one of his eleven books. Lillian Carter worked with leprosy patients in India long after what many would consider retirement age.

CARTER: She epitomized, in my opinion, what a human being ought to be. She was in India when she was 70 years old. She was looked upon then as an untouchable, because she dealt with blood and human feces and so forth. But that was a transforming experience in her life, even at that age.

DE SAM LAZARO: Jimmy Carter is now 85, and he may well live to see the eradication of a disease from the planet for the first time since small pox was eliminated in the early 1970s.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Juba, Southern Sudan.