In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

A High Court with No Protestants

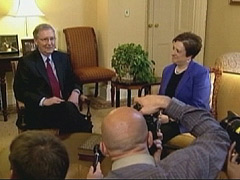

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan made the rounds in Washington this week, introducing herself to the senators who will vote on her confirmation as the newest justice on the High Court. Special interest groups, many of them religious, are already urging specific lines of questioning for the upcoming hearings. If she is confirmed, Kagan would become the third Jewish justice and the third woman on the current court.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA (at announcement of Supreme Court nomination): A court that would be more inclusive, more representative, more reflective of us as a people than ever before.

ABERNETHY: Kagan’s confirmation would also mean that for the first time in American history the Supreme Court would have no Protestants. Does this matter? If so, what does it say about the place of Protestantism in America today? Joining me is Kim Lawton, our managing editor. Kim, I want to have a little discussion about this. People are saying, Protestants are saying, well, yes, this is a big symbol and they’re sad about it, of declining Protestant influence in this country. But at the same time I hear other people saying it’s really good news, because it is a symbol of how far the country has come in overcoming the anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish prejudice that existed for so long—still exists, but there’s been a lot of progress made on that. And they also say it matters a lot more what somebody thinks, a Supreme Court justice thinks, on a particular issue than what kind of religious label that person wears. You hear that?

ABERNETHY: Kagan’s confirmation would also mean that for the first time in American history the Supreme Court would have no Protestants. Does this matter? If so, what does it say about the place of Protestantism in America today? Joining me is Kim Lawton, our managing editor. Kim, I want to have a little discussion about this. People are saying, Protestants are saying, well, yes, this is a big symbol and they’re sad about it, of declining Protestant influence in this country. But at the same time I hear other people saying it’s really good news, because it is a symbol of how far the country has come in overcoming the anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish prejudice that existed for so long—still exists, but there’s been a lot of progress made on that. And they also say it matters a lot more what somebody thinks, a Supreme Court justice thinks, on a particular issue than what kind of religious label that person wears. You hear that?

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: Well, it is interesting. I mean, nobody is saying that she shouldn’t be confirmed because it throws the religious balance of the court out, or anything like that, but it has been a very interesting moment to take stock of this change in our society. But, yeah, what I’m hearing from people, what I heard from one Protestant pastor this week was he said to me I’m less concerned about her religious affiliation than I am about how she’s going to vote on, for example, some of the religion cases, and certainly that those ideas of the separation of church and state and what kind of relationship the government and religion should have—that’s been very controversial. There have been some very close decisions on the court, and so what she thinks about that, for example, is going to have a big impact no matter what kind of religious label she carries.

ABERNETHY: Yeah. There’s also this idea that has been spoken of this week sometimes about a Protestant worldview and how it’s important—Protestants after all are half the country, 51 percent, but still pretty close to half—that there is such a thing as a Protestant worldview and that this needs to be represented on the court. But is there such a thing as a Protestant worldview anymore?

LAWTON: Well that’s been really interesting for me this week to watch or to read what some people are saying just in terms of that notion. Of course people’s faith, their beliefs affect their worldview, affect how they look at things, their values. But is there a uniquely Protestant worldview in this kind of situation? There are certainly a lot of different kinds of Protestants, and even when the court had all Protestants they didn’t have all unanimous decisions, so I do think it’s been an interesting question that’s been raised.

ABERNETHY: And it doesn’t mean that there can’t ever in the future be another Protestant justice.

LAWTON: Well, certainly the Protestant influence in America is not going anywhere. I mean, our president is Protestant, we’ve only had one non-Protestant president, the majority of the US Congress is Protestant. Protestants still are a vibrant community in this country and still very influential, but things are different than they used to be.

ABERNETHY: Kim Lawton, many thanks.