In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Indiana Doctor in Kenya

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: At the start of this year, in Kenya in East Africa, terrible, largely tribal violence took more than a thousand lives and drove hundreds of thousands from their homes. But there were a few compounds of safety, among them the clinics run by an American doctor. There, Kenyans of different tribes found common ground in their Christian faith. Such sanctuary was one of the many outgrowths of a ministry that began with one small anti-AIDS clinic and now serves 60,000 patients with the back-home support of a church in Indiana. Fred de Sam Lazaro has the story.

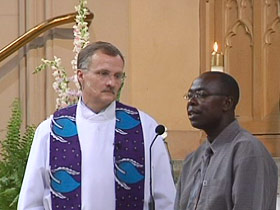

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: From its location on the edge of the city, the North United Methodist Church in Indianapolis boasts a number of global ties.

Reverend KEVIN ARMSTRONG (Pastor, North United Methodist Church, Indianapolis, speaking to Joseph Okuya from Kenya): Joseph, please come here and join me as we welcome you.

DE SAM LAZARO: None are closer than those to Kenya.

Rev. ARMSTRONG (speaking to Mr. Okuya): As you know, we’ve been praying with and for you, for the people of Kenya. It helps us to know a little bit from you. How are things now?

DE SAM LAZARO: The honored guest told of the deadly post-election violence in his country.

JOSEPH OKUYA: Of course, we see that at the peak the leaders have made some kind of an agreement. But down in the grassroots, it’s still smoldering.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Kenya connection traces back almost two decades to one couple from this congregation. In recent months, Joseph and Sara Ellen Mamlin have brought them news from the frontlines of a distant conflict.

Dr. Joseph Mamlin first visited here in the late ’80s to set up an exchange program between his employer, Indiana University School of Medicine and a med school in the western Kenyan city of Eldoret. He returned a decade later to a worsening AIDS problem here and decided stay on and set up a small HIV clinic — or so he thought.

Dr. JOSEPH MAMLIN: It grew to where I had 1,500 patients out of this one room and just lying all around on the ground. We had the largest village-based HIV clinic in Kenya, and we were just working out of this one room. And then I was home visiting my children and grandchildren years ago, and someone called my wife and asked to meet her at J.C. Penney at a shopping mall. And she just anonymously handed her a check and said, “Joe needs a clinic.” And this is what you see here. This is all from an anonymous donor in Indianapolis from the church.

We had the National Minister of Health and the U.S. Ambassador dedicating, but, that’s not the real dedication. Here I see a beautiful lady coming by here. This is Rose Beargen. She’s one of the very first patients I treated here many years ago. And I’m the one looking sick now instead of her. And — but she was essentially dying of PCP pneumonia. She was almost a dead woman.

DE SAM LAZARO: Today she runs the clinic’s outreach program. The miracle of her recovery began in this pharmacy. It’s well-stocked with antiretroviral drugs for HIV, thanks to a major grant from the U.S government’s President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief or PEPFAR.

Dr. MAMLIN: Look what we have here. This is PEPFAR in action. People who’ve been in this business and watching people die in Kenya will walk in a room like this, they will cry. To see this umbilical cord to life made available by the American people free of charge for all of these patients is a miracle. And it’s just simply wonderful.

DE SAM LAZARO: Today, some 60,000 patients receive care in 18 regional centers. Mamlin notes only two American doctors work alongside several hundred Kenyan colleagues and staff, a staff so dedicated, he says, that many were on the frontlines of emergency care during the turmoil. None of the acrimony from the ethnic violence that followed December’s elections spilled into the compounds of their clinics.

HENRY MUITIRIRI: I think in the organization we didn’t have any inciter who could come and incite us to fight. We work as one.

DE SAM LAZARO: Many employees took shelter in the project’s compound. Even though they were from tribes fighting each other on the outside, they drew on faith to stay together inside.

PANINAH MUSULA: We had a Christian group. We had prayers. We had to sing together. We had to pray together. That united us that we could not rise against one another.

SAMMY KIMANI: We need to believe that we can have peace back, and we need it. We had hope.

DE SAM LAZARO: But all around them the devastation did not spare even churches — the toll not just in death and property damage, but also interruption in the careful drug regimens for AIDS patients.

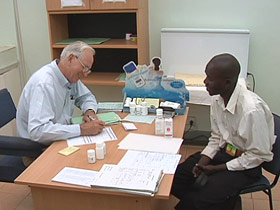

Dr. MAMLIN (talking with patient): You missed two days.

UNIDENTIFIED PATIENT: There was no means to come here.

Dr. MAMLIN: I want you to know that missing your medicine even two days is dangerous. I know you could do nothing. It’s not your fault.

DE SAM LAZARO: The most immediate challenge was in tracking down the thousands of patients who fled the violence, making sure they were supplied with their drugs. Many scattered into makeshift camps for displaced people, some of which still remain. Thirty-seven-year-old Purity Wambui took shelter in this church. She got a coveted indoor spot since she has a newborn. That makes life easier, but hardly easy.

PURITY WAMBUI: The health becomes deteriorated because you have nothing to eat. Before, we used to have balanced diet, but now it’s hard to get that balanced diet. We just rely on maize and yellow peas. Milk — milk is a dream.

DE SAM LAZARO: Nonetheless she’s grateful, not just for drugs that have kept her alive but for provisions the Indiana partnership distributes to her entire family. It’s the middle step in restoring patients, says Mamlin.

Dr. MAMLIN: When I first pick up a patient who’s wasted, they look up at me and you can tell, even if they say nothing, they just want the drugs so they can live. And about six or eight weeks, when they see that they’re living, they kind of look back at you and say, “I’m hungry!” And then let another two or three months go by as they are walking around and looking normal, they wonder how do I get back on my feet and become a whole person again?

DE SAM LAZARO: That takes clinics into matters far beyond the immediate medical needs. Each day there are tough calls to make on how to disburse limited funds.

Dr. MAMLIN (speaking to patient): You have no school fees?

DE SAM LAZARO: Mamlin turned down this mother’s request for school fees.

Dr. MAMLIN (reading request from patient): “To whom it may concern.” That’s usually my middle name. No, you have to see Diana, the social worker. There are so many of these it’s impossible for me to do all of them

DE SAM LAZARO: The next patient, a tailor named Clement, was luckier.

CLEMENT (speaking to Dr. Mamlin): When I went out to vote, but when I came back they looted my house.

DE SAM LAZARO: Luckier, that is, for someone who’d lost all his belongings, including his sewing machine.

Dr. MAMLIN (to Clement): I have some friends in U.S., and they’ve donated a little bit money for me to use. So I’m going to qualify you for that, and I’ll get you a machine, and I’ll get you materials to get back in business.

CLEMENT: I thank you very much, sir.

Dr. MAMLIN: Do you want to reconstitute immune systems or do you want to reconstitute lives? And those are two totally different problems, and we’ve decided to go after lives. We’re taking care of the poorest of the poor.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s a choice that may be rooted in faith, but faith is a matter Mamlin does not share publicly.

Dr. MAMLIN: I have much more concern about what needs to be done as an expression of whatever faith system we have. I guess I’m raised in tradition that tends to avoid putting things like that on your shoulder.

Rev. ARMSTRONG: There’s a wise old church leader who said preach the Gospel and, if necessary, use words.

DE SAM LAZARO: Back in Indianapolis, Pastor Armstrong says what began as a public health program has also spawned numerous exchanges between worship communities here and in Kenya. For the Hoosiers, he says it’s widened their understanding of a distant land and a complex epidemic, and it’s helped them spiritually.

Rev. ARMSTRONG: Who are the people you want your children to learn the Christian faith from? The Mamlins would be at the top of that list. And so for us to be able to find some way to be alongside them in their journey not only was a way for us to strengthen our friendship but also for us to deepen our own faith.

DE SAM LAZARO: For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro.