In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

- Moral Wounds of War

- Sharing the Burden of War

- Jonathan Shay Extended Interview

- Nancy Sherman Extended Interview

- Lt. Col. Eric Olsen Extended Interview

- Michael Abbatello Extended Interview

- Ed Tick Extended Interview

- Religious Hiring Rights

- Stanley Carlson-Thies Extended Interview

- Barry Lynn Extended Interview

- Listen Now

Religious Hiring Rights

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: It’s graduation time at the Helping Up Mission, a nondenominational Christian ministry for poor and homeless men in Baltimore. On this day, several men are being recognized for reaching new stages of success in their recovery from drug and alcohol addiction. Helping Up believes that spirituality plays a key role in the recovery process, and it wants those who work there to reflect its values. The ministry relies largely on private donations, but it has received some public funding as well, and that raises a difficult question: If the mission takes government money, should it still be allowed to only hire people who share its religious beliefs?

BOB GEHMAN (Executive Director, Helping Up Mission): A faith-based organization is only faith-based if it can hire people of the particular faith that it espouses, so if, for instance, we were not able to discriminate in our hiring practices based on our faith and religion, that would change us.

BARRY LYNN (Executive Director, Americans United for Separation of Church and State): I don’t think that there’s any moral or ethical or constitutional justification for a religious group taking government funds, tax dollars, and saying we’re only going to hire the people we want, we’re going to have a religious litmus test for hiring. That’s dead wrong, and it should be stopped.

LAWTON: For decades, religious groups have been partnering with the government to provide a host of social services in the US and around the world. Those partnerships attracted new visibility—and new controversy—after President George W. Bush created his faith-based initiative—

LAWTON: For decades, religious groups have been partnering with the government to provide a host of social services in the US and around the world. Those partnerships attracted new visibility—and new controversy—after President George W. Bush created his faith-based initiative—

PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH: People who don’t have hope can find hope.

LAWTON: —in his words “to level the playing field” so that more religious groups could compete for government grants.

A series of laws, regulations and court decisions have tried to ensure that the faith-based partnerships don’t violate the Constitution. For example, tax dollars may not be used to fund proselytizing. But the issue of religious hiring remains one of the most contentious questions. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its regulations banned discrimination in hiring but granted faith groups an exemption, allowing them to hire on the basis of religion. But Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, says federal funding should change the calculus.

LYNN: Whenever government money enters the picture, then the civil rights rubric of our country is you don’t get to discriminate anymore. If you’re engaged in federal work with federal money, you really have to play by the same rules as everyone else. You don’t get to be a bigot, you don’t get to discriminate, you don’t get to select people for a job or fire people from a job because of their religious beliefs or orientation.

LAWTON: Stanley Carlson-Thies heads the Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance, which helps faith-based groups protect their identity and practices. He says the law allows religious groups to create an organizational philosophy as other federally funded entities do.

LAWTON: Stanley Carlson-Thies heads the Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance, which helps faith-based groups protect their identity and practices. He says the law allows religious groups to create an organizational philosophy as other federally funded entities do.

STANLEY CARLSON-THIES (Executive Director, Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance): I think the faith groups see it as, you know, like a Democratic senator hires Democrats for his or her office, and environmental groups hire environmentally sensitive people, and so on, and they say hey, we’re a faith group, it’s faith that motivates us, defines us, so we’re looking for people who are, share that faith.

LAWTON: Carlson-Thies sees this as an issue that pits an individual’s rights against institutional rights. He says for faith groups it’s not discrimination in the traditional sense.

CARLSON-THIES: It’s not that they think of this as you grew up on the wrong side of the tracks, we’re going to keep you out. No, it’s more do you share the things that motivate us? Do you have the same set of values? Do you have the same set of behaviors?

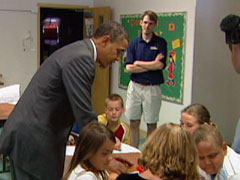

LAWTON: On the presidential campaign trail in July 2008, candidate Barack Obama visited a Christian youth program in Zanesville, Ohio, and promised that his administration would continue partnerships between faith-based groups and the government. But he said there would be a few caveats.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: First, if you get a federal grant you don’t use that grant money to proselytize to the people you help, and you can’t discriminate against them, or against the people you hire, on the basis of their religion.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: First, if you get a federal grant you don’t use that grant money to proselytize to the people you help, and you can’t discriminate against them, or against the people you hire, on the basis of their religion.

LAWTON: When President Obama set up his White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, many civil rights groups expected to see all religious hiring preferences banned in federally funded programs. That hasn’t happened. Instead, Joshua DuBois, head of Obama’s faith office, has outlined a different course.

JOSHUA DUBOIS (White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, in speech): With regard to the issue of co-religionist hiring, hiring discrimination hiring, it’s a difficult topic and one that where there are very clear and strong opinions on both sides. The president has decided to take a case-by-case approach, and as difficult legal issues arise he wants me to work with the White House counsel, with the attorney general, to explore those issues and give him a recommendation.

LYNN: A case-by-case basis is like saying, well, maybe Rosa Parks may be in the front of the bus; other African-American women, they get into the back of the bus. There is no way to deal with fundamental civil rights issues on a case-by-case basis.

LAWTON: Both Carlson-Thies and Lynn were on a task force about government partnerships for Obama’s Faith Advisory Council. But the hiring question wasn’t allowed to even be part of the discussion. It’s an issue of deep concern for many faith-based charities, including Helping Up in Baltimore. The residential addiction recovery program has about 400 homeless addicts who live here for at least a year. They go through a 12-step program and receive counseling, medical help, job training, and Bible study. Executive director Bob Gehman says faith is crucial in the program’s effectiveness.

GEHMAN: Many of our men here have tried other programs, and they’ve come to us because they particularly like the faith-based ingredient that we have here. It offers them the kind of hope that they need in order to get beyond all the failures that they’ve had in the past.

LAWTON: That was the case for Michael Anthony Gross, who came here after three decades of cocaine and heroin addiction.

MICHAEL ANTHONY GROSS (Helping Up Mission): When I was in detox, I talked to a gentleman, and he recommended the Helping Up Mission, and he spoke about the spiritual basis that, you know, the program is run on, and I come to know that after all these years that’s what I was missing.

MICHAEL ANTHONY GROSS (Helping Up Mission): When I was in detox, I talked to a gentleman, and he recommended the Helping Up Mission, and he spoke about the spiritual basis that, you know, the program is run on, and I come to know that after all these years that’s what I was missing.

LAWTON: The mission’s internal surveys have found that two years out, almost 80 percent of the men who complete the program are still drug-free and employed. The program accepts men from all religious backgrounds, and leaders say religion isn’t imposed on anyone. The men may opt out of chapel or Bible study, but if they do they must attend another 12-step-style meeting. Tom Bond is Helping Up’s program director, who in 2002 came here himself as a homeless addict.

TOM BOND (Helping Up Mission): The whole faith and recovery both are highly unique. What we do is we just try to kind of create a platform and a vehicle for these guys to succeed and make things available to them and let them figure things out for themselves, not force it on them.

LAWTON: Gehman says the mission has been careful not to use any public money for the explicitly religious parts of the program. But he says hiring people who share the mission’s faith is central to maintaining its identity. If the government makes nondiscrimination a condition, they wouldn’t be able to accept public funding, and he says that would give other groups an unfair advantage.

GEHMAN: It really gives secular organizations a real power-edge, because they’re fully funded. They can build their buildings, they can develop their programs, and the faith-based organizations are left to have to raise their own money, which is becoming increasingly difficult.

GEHMAN: It really gives secular organizations a real power-edge, because they’re fully funded. They can build their buildings, they can develop their programs, and the faith-based organizations are left to have to raise their own money, which is becoming increasingly difficult.

LAWTON: Indeed, says Carlson-Thies, if the administration changed the longstanding policy, many charities from across the religious spectrum may be forced to end their partnerships with the government.

CARLSON-THIES: It’s not that we just say, well fine, if you want to walk away, walk away, because this implicates billions of dollars and a big volume of services.

LAWTON: One organization that might be affected is World Vision, the largest US-based relief and development group. World Vision has been taking federal funds since 1983 and last year received more than $300 million in cash and goods from the government. The Christian group wants to maintain the right to consider religion in its hiring. World Vision’s chief legal officer told me his organization has never discriminated among its recipients or engaged in illegal hiring practices. But, he said, if the policy changes and World Vision can no longer partner with the government, “the losers would be children in need around the world and American taxpayers.”

LYNN: Scientific studies certainly don’t prove that World Vision is the only group that can help the poor around the world, nor does it suggest that the best charities at home are those that have a religious title affixed to their name.

LAWTON: Under strong pressure from both sides, the Obama administration has been reluctant to clarify its position or make any changes, and White House officials declined to comment for this story as well. But with several court cases moving in the pipelines, the issue isn’t going away.

I’m Kim Lawton in Washington.