Mark C. Toulouse: Pledging Allegiance to the Pledge

Everybody loves to spin a top, and during political seasons everybody loves to spin whatever seems spin-able. First, someone spins it to the left, and then somebody else spins it to the right. Those who are experts in the art of spinning never want the spinning to stop. For when the spinning stops, things might be seen for what they are.

The words and records of the candidates are always subject to the spin experts. Lately, the spin doctors have had a run at an answer Sarah Palin provided on a questionnaire for the conservative Eagle Forum Alaska during her run for the governor’s office in 2006. The question posed by the forum was, “Are you offended by the phrase ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance?” “Not on your life,” Palin responded. “If it was good enough for the Founding Fathers, it’s good enough for me, and I’ll fight in defense of our Pledge of Allegiance.”

The words and records of the candidates are always subject to the spin experts. Lately, the spin doctors have had a run at an answer Sarah Palin provided on a questionnaire for the conservative Eagle Forum Alaska during her run for the governor’s office in 2006. The question posed by the forum was, “Are you offended by the phrase ‘under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance?” “Not on your life,” Palin responded. “If it was good enough for the Founding Fathers, it’s good enough for me, and I’ll fight in defense of our Pledge of Allegiance.”

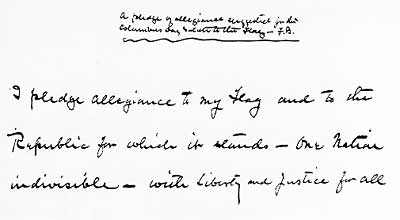

Without going into much detail, the Anchorage Daily News quickly pointed out to its readers (October 16, 2006) that Palin evidently had false assumptions about history. The founders, of course, did not have anything to do with the Pledge of Allegiance. Francis Bellamy, a Baptist minister, authored the pledge in 1892 as part of an effort by President Benjamin Harrison to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America. Bellamy and the magazine he was associated with hoped to use the pledge to promote the sale of American flags to public schools in order to raise money for their work. A joint resolution of Congress codified the pledge into public law in 1942. Later, following many years of lobbying efforts by the Knights of Columbus and the American Legion, Congress amended the pledge in 1954 by adding the words “under God.” The amended version became official on Flag Day that year, but prior to then the pledge, even though written by a minister, did not mention God at all.

In late August, shortly after Senator McCain’s selection of Palin, the blogging started. The Daily Kos, a liberal blog, responded to Palin’s pledge to the pledge by describing her as a “female George Bush,” a phrase meant to describe someone who is not particularly bright and who has no literate sense of history. In mid-September, Ann Coulter, the conservative political analyst and lawyer, responded with her spin that Palin did not, by her comments, mean to imply that the “founding fathers’ wrote the pledge of allegiance, but rather that “the founding fathers believed this was a country ‘under God’.” “Which,” wrote Coulter, “um, it is.”

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that the right is right (perhaps a stretch, but…). If Palin did not intend to imply that she thought the founders authored the pledge, she meant to emphasize that they believed wholeheartedly in the proposition that America is a country “under God,” just like, one must also assume, Palin believes is the case today. It is certainly defensible to argue that most of the founders believed America needed to take God seriously. Even the deists, like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, hardly conventional Christians in the loosest consideration of that description, believed America was subject to the judgment of God. Evidence of the founders’ sense of God’s judgment on all nations and peoples is evident throughout their writings. Though they could connect God’s will to particular national enterprises, as in the case of the American Revolutionary War, they usually used language about the divine to emphasize accountability of the country (and all countries) to God.

Handwritten pledge |

The founders were certainly comfortable with language about God, but they did not use the phrase “under God” (there is no written record of the founders ever using it). Instead, “under God” became commonplace in American public life only after World War II, particularly during the Cold War, when America sought to convince itself and the world that God was on America’s side in opposing “atheistic communism.” This twentieth-century notion, shared by Sarah Palin and other socially conservative Christians, emphasizes that “under God” means that God stands with America, that America is God’s chosen country. It developed naturally out of twentieth-century events, like the victories in two major world wars and the rapid accumulation of wealth after America successfully dealt with the difficulties of the Great Depression. The rise of the religious right since the 1970s has only solidified these assumptions.

This developing American belief in God’s automatic blessing also possesses significant roots in the previous century. The events surrounding American expansionism during the nineteenth century, including Manifest Destiny, imperialism, and rapid urbanization and industrialization, caused Americans to turn more comfortably to using God-language to describe America’s goodness and to communicate how America was better than any other country in the world because it was “under God.”

The point here is that the founders’ notion of what it meant to be a country that takes God seriously is, historically, quite distinct from the notion that operates in many Christian and political communities today, which is much more like saying God takes America seriously.

Palin’s pledge to the pledge and to “under God” has other interesting implications. In a 2004 Supreme Court decision about the constitutionality of reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools, the Court temporarily avoided the issues in the case by stating that Michael Newdow, the atheist suing on behalf of his daughter, did not have standing to sue because he was not the custodial parent. The arguments of the case, however, contained an ironic twist that Sarah Palin has likely never considered. The two attorneys arguing to keep “under God” in the pledge did so by stating that the phrase “one nation under God” is simply a “political philosophy,” merely “ceremonial” in nature and not at all a “religious exercise.” Ironically, it was Newdow who argued that the words are truly religious and should be taken seriously. In fact, a brief submitted by religious leaders supported Newdow’s efforts to remove the phrase precisely because, as currently understood, the Pledge of Allegiance forces Christian children to take God’s name in vain every day. Using God’s name ritualistically, or in simply ceremonial fashion, is to take God’s name in vain.

Perhaps those like Sarah Palin who consider themselves committed Christians who believe in the holiness of God should reconsider their resolve to support national and cultural tendencies to use God’s name merely ceremoniously or as a way to provide divine sanction for all things American. Genuine concern for the holiness of God just might demand it.

— Mark G. Toulouse is professor of American religious history at Brite Divinity School at texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas, and the author of GOD IN PUBLIC: FOUR WAYS AMERICAN CHRISTIANITY AND PUBLIC LIFE RELATE (Westminster John Knox Press, 2006).