Daniel K. Williams: A Victory for the Christian Right

Immediately after the 2010 midterm elections, the National Right to Life Committee declared the results a victory for the pro-life cause, claiming that 65 seats in Congress had switched from pro-choice to pro-life. The Family Research Council likewise declared that voters had soundly rejected President Barack Obama’s efforts to allow gays to serve openly in the military. Voters in Iowa recalled three state Supreme Court justices who had ruled in favor of same-sex marriage. Across the nation, Christian conservatives claimed victories for their cultural causes after seeing Tuesday’s election results. Why, then, did most of the media—and the Republican Party leadership—say so little about religion in the election analysis?

Republicans gave the public the impression that the party was ignoring social issues in this election cycle because they knew that they could win without relying on the so-called “wedge issues” that are popular with a component of their base but that have the potential to alienate a broader electorate. Nearly 40 percent of Republican voters are conservative evangelicals who can be mobilized on cultural issues, but the GOP risks alienating moderates and independents by emphasizing the Christian right’s positions on gay rights and abortion. John McCain, for instance, increased his support among Christian right activists by choosing the conservative evangelical Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, but the choice cost him support among moderates.

Republicans gave the public the impression that the party was ignoring social issues in this election cycle because they knew that they could win without relying on the so-called “wedge issues” that are popular with a component of their base but that have the potential to alienate a broader electorate. Nearly 40 percent of Republican voters are conservative evangelicals who can be mobilized on cultural issues, but the GOP risks alienating moderates and independents by emphasizing the Christian right’s positions on gay rights and abortion. John McCain, for instance, increased his support among Christian right activists by choosing the conservative evangelical Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008, but the choice cost him support among moderates.

The safest strategy for the GOP is to focus its message on the economy or other issues that are not culturally polarizing. The party has generally emphasized social issues only as a last resort in years when party leaders do not think they can win by talking about economics. In 1972, when the Republican Party experimented with a strategy of cultural conservatism, President Richard Nixon’s White House aide H.R. Haldeman admitted that the Republicans were emphasizing “patriotism, morality, religion, not the material issues of taxes and prices” in the president’s reelection campaign mainly because “if those [economic matters] were the issues, the people would be for McGovern.” Similarly, the Republicans acquiesced to the Christian right’s push to emphasize social issues in 1992, and again in 2004, because they could not win on their economic record in those years. But in 2010, Republicans saw an opportunity to win an election by appealing to popular economic discontent.

The Republican Party’s decision to emphasize the economy more than social morality does not mean that the GOP’s victory on Tuesday meant nothing to social conservatives. On the contrary, they realize that Tea Party Republican candidates, who are ostensibly libertarian, share the Christian right’s positions on social issues. Senator-elect Rand Paul (R-KY), who opposes abortion rights, courted Christian right support during the campaign with an endorsement from James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family. The Tea Party’s unofficial national leaders, including Representative Michele Bachmann (R-MN) and Senator Jim DeMint (R-SC), likewise oppose abortion rights and same-sex marriage. The Christian right may not have been in the limelight on Tuesday night, but its causes were advanced just as much as if it had been.

When John Boehner (R-OH) takes the speakership of the House, conservative evangelicals can quietly celebrate their victory. They may not have been the focus of media coverage during the campaign, but they know the Republican victories on Tuesday were a victory for their cause as well.

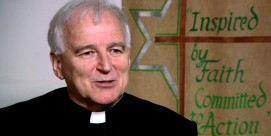

Daniel K. Williams is an assistant professor of history at the University of West Georgia and the author of “God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right” (Oxford University Press, 2010).