In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Look Ahead 2011

BOB ABERNETHY, host: Welcome, I’m Bob Abernethy. It’s good to have you with us. Today, a special report on the events and issues we see ahead in 2011. We do this with the help of Kim Lawton, managing editor of this program, Kevin Eckstrom of Religion News Service, and E.J. Dionne of the Brookings Institution, the Washington Post, and Georgetown University. Before we begin our discussion, as we close out the first decade of the new millennium we remember some of the stories that set the stage for the news we expect to cover in 2011 and beyond. Our managing editor Kim Lawton took a look back at the events of the last decade.

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 were perhaps the defining moment of the decade, and the repercussions are still being felt on many fronts. In the wake of the tragedy, mainstream Muslim leaders tried to spread a message that Islam is not synonymous with terrorism. But those efforts were complicated by an expanding extremist movement that recruits over the Internet, as well as several high-profile arrests of Muslims plotting more attacks. American Muslims worked to define their place in US society, but many felt unfairly targeted by enhanced security measures and what they saw as a rising tide of Islamophobia. President Obama made improving relations with the Muslim world one of the priorities of his new administration.

The 9/11 attacks led to American involvement in long and difficult wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Religious and ethical leaders debated whether each conflict was just. President George W. Bush argued for a doctrine of preventive war, the idea that it was moral to attack a country to prevent it from attacking us first. The ethical debates intensified with revelations that the US was using torture as a means of getting information. After thousands of deaths of troops and civilians, President Obama announced the end of combat operations in Iraq and the intention to begin withdrawing from Afghanistan.

The 9/11 attacks led to American involvement in long and difficult wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Religious and ethical leaders debated whether each conflict was just. President George W. Bush argued for a doctrine of preventive war, the idea that it was moral to attack a country to prevent it from attacking us first. The ethical debates intensified with revelations that the US was using torture as a means of getting information. After thousands of deaths of troops and civilians, President Obama announced the end of combat operations in Iraq and the intention to begin withdrawing from Afghanistan.

Economic crises dominated much of the end of the decade as recession, unemployment and foreclosures took a toll on faith-based groups and the people they serve. Religious institutions were forced to slash their budgets and lay off staff even as they were asked to do more to help needy people.

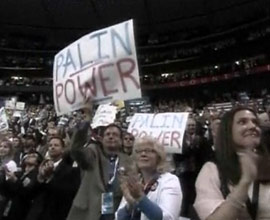

Religion continued to be a potent force in politics. In 2000 and 2004, President Bush rallied religious conservatives. He set up a new White House office to expand government partnerships with faith-based social service organizations. Analysts spoke of a God gap, with voters seeing the Democratic Party as unfriendly toward religion. In the run-up to the 2008 elections, Democrats and the Obama campaign developed an unprecedented outreach to compete for religious votes. Many in that faith coalition were disappointed the Democrats didn’t build on the momentum in the 2010 midterm elections. Meanwhile, religious conservatives were energized by the Tea Party movement and vowed new activism leading up to the 2012 elections. Religious groups across the spectrum were involved in policy debates, from health care to immigration and gay marriage.

Issues surrounding homosexuality provoked bitter debates within religious institutions and American society as a whole. The 2003 election of Gene Robinson as the first openly gay bishop in the US Episcopal Church brought the worldwide Anglican Communion to the brink of schism, even as other denominations continue to debate the role of gay clergy. In 2003, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage, with four other states and the District of Columbia following suit. The issue continues to work its way through the courts.

Issues surrounding homosexuality provoked bitter debates within religious institutions and American society as a whole. The 2003 election of Gene Robinson as the first openly gay bishop in the US Episcopal Church brought the worldwide Anglican Communion to the brink of schism, even as other denominations continue to debate the role of gay clergy. In 2003, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage, with four other states and the District of Columbia following suit. The issue continues to work its way through the courts.

For the Roman Catholic Church, a dramatic changing of the guard with the 2005 death of John Paul II, who had been pope for more than 25 years, and the election of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI. For the US Catholic Church, much of the decade was focused on addressing a massive clergy sex abuse crisis, enacting new guidelines to prevent abuse, and confronting litigation that saw more than two billion dollars in payouts to victims. In 2010, the clergy abuse scandal exploded across many parts of Europe and posed new challenges to the Vatican and top church leaders.

The new millennium began with a sense of relief that a predicted Y2K computer meltdown never materialized. It ends with the development of social media like Facebook and Twitter offering new online possibilities for personal connection and outreach, enabling information to be disseminated at lightning speed—both for good and for ill.

ABERNETHY: Kim, many thanks for that. Welcome to you, to Kevin Eckstrom, and to E.J. Dionne. E.J., we have a new Congress, Republican control of the House, more Republican votes in the Senate. Walk us through that a little bit. What do you expect that will mean for some of the social issues that are of most concern to religious communities?

EJ DIONNE (Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution): You know, watching Kim’s set-up piece I was thinking of Yogi Berra’s great line: ‘Predictions are hard, especially when they’re about the future.” And who would have imagined a decade unfolding the way this last decade just unfolded? So I think we’re all in a difficult situation here. I think when you look forward to this Congress, so much of it is not going to be about social issues. The last Democratic Congress kind of acted to get some of those out of the way, notably don’t ask don’t tell. I think they really wanted that through because they knew it was going to be very difficult this time over. You may have some debate about abortion around the healthcare bill. Republicans want to repeal it. I don’t think they’ll be able to but they going to have a variety of ways of trying to hem in President Obama in sort of putting it into effect. So I think you may see it there. I think one of the sleeper issues will be fights we might have around the National Endowment of the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, where you have, if nothing else for purely political reasons it’s a question where conservatives can talk about it as an economic issue: should we be spending the money? But there are always issues related to cultural values that get into those debates. So I suspect you are going to see some of those arguments around the humanities and arts endowments. Personally, I hope it doesn’t happen that way, but I think that is going to happen.

EJ DIONNE (Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution): You know, watching Kim’s set-up piece I was thinking of Yogi Berra’s great line: ‘Predictions are hard, especially when they’re about the future.” And who would have imagined a decade unfolding the way this last decade just unfolded? So I think we’re all in a difficult situation here. I think when you look forward to this Congress, so much of it is not going to be about social issues. The last Democratic Congress kind of acted to get some of those out of the way, notably don’t ask don’t tell. I think they really wanted that through because they knew it was going to be very difficult this time over. You may have some debate about abortion around the healthcare bill. Republicans want to repeal it. I don’t think they’ll be able to but they going to have a variety of ways of trying to hem in President Obama in sort of putting it into effect. So I think you may see it there. I think one of the sleeper issues will be fights we might have around the National Endowment of the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, where you have, if nothing else for purely political reasons it’s a question where conservatives can talk about it as an economic issue: should we be spending the money? But there are always issues related to cultural values that get into those debates. So I suspect you are going to see some of those arguments around the humanities and arts endowments. Personally, I hope it doesn’t happen that way, but I think that is going to happen.

ABERNETHY: How about immigration?

LAWTON: Well, I was going to say that I am going to be watching to see how some of the evangelical political activists maneuver with the Tea Party politicians that got elected. You know, in this last election there was so much talk about how the Tea Party was so ascendant and there were a lot of religious conservatives that were supportive of the Tea Party. But when you get to issues like immigration or some of the other issues involving a social safety net for the poor, evangelicals don’t always line up as economic conservatives. And so while they might be hoping for some action on abortion or maybe even some of the gay marriage type issues—I don’t know that that’s going to come up in Congress, but I’m going to be watching some of the economic issues that do have some moral implications to see how much evangelicals, and some Catholics who were supportive of the Tea Party—where they come down.

ECKSTROM (Editor, Religious New Service): Right, and there are a lot of moral issues that a lot of religious groups care about. And so I think what you’re going to have is maybe a different set than what we’ve seen in the last couple years. Whereas under the Democratic Congress we were talking about moral issues like the environment and the minimum wage increase and things like that, you’re probably not going to see as much of that with a Republican House. Instead, you’ll have issues that maybe more conservatives tend to latch on to. But it’s not that these social issues are going to disappear, it’s just that there are going to be a different set of them.

ECKSTROM (Editor, Religious New Service): Right, and there are a lot of moral issues that a lot of religious groups care about. And so I think what you’re going to have is maybe a different set than what we’ve seen in the last couple years. Whereas under the Democratic Congress we were talking about moral issues like the environment and the minimum wage increase and things like that, you’re probably not going to see as much of that with a Republican House. Instead, you’ll have issues that maybe more conservatives tend to latch on to. But it’s not that these social issues are going to disappear, it’s just that there are going to be a different set of them.

DIONNE: That’s a good point, because you are going to talking more and more about budget deficits and cuts in government programs, and I think it’s going to be fascinating to see how religious groups that sometimes seem to be aligned with conservatives on some of the cultural questions are actually going to be saying no, you can’t cut this program for the poor or that program for the poor, because there are a lot of Catholics, a lot of evangelicals, and many in the rest of the religious community—mainline Protestants, Jews, Muslims—who really want to protect some of those programs. So I think their voices are actually going to be very important at a time of budget stress.

ECKSTROM: And one issue I think that’s worth watching that we’ve already seen indications of is that House Republicans want to hold hearings on American Muslims and the radicalization of American Muslims – sort of home-grown terror threats – and what’s going wrong within American Islam that it’s allowing this to happen? So it’s a different kind of religious issue but one that’s already going to be on Congress’s agenda.

ABERNETHY: Before we leave that, E.J., what about the tone, the spirit that you expect. Is it going to be awful?

DIONNE: I’m not very optimistic that we’re going to see an outbreak of comity and friendship across party lines. On the Muslim hearings, having Congress sort of investigate a religious group in the country raises all kinds of questions, which I hope get raised. I’m not sure that the deal that President Obama reached with the Republicans on taxes can be easily replicated across other issues. After all, tossing out about $858 billion is a lot easier than cutting $400 billion or whatever they decide to do. So I think it’s going to be a very difficult couple of years.

LAWTON: And also, sort of in the backdrop, this coming year in politics is going to be the run up to the 2012 presidential election, and so that’s going to be complicating anything anyone wants to get done because there’s going to be a lot of posturing as people try to set themselves up for the next presidential election.

LAWTON: And also, sort of in the backdrop, this coming year in politics is going to be the run up to the 2012 presidential election, and so that’s going to be complicating anything anyone wants to get done because there’s going to be a lot of posturing as people try to set themselves up for the next presidential election.

DIONNE: Which brings us to some very interesting debates inside the Republican Party. Your point about the Tea Party and the Christian conservatives overlapping but distinct groups—how are they going to play those roles inside the Republican fight for the nomination?

LAWTON: And a lot of religious conservatives were very unhappy with the Republican establishment, felt like they took them for granted, Republicans took the religious conservatives for granted—wanted them to come out and work and vote but didn’t necessarily take care of their issues. It will be interesting to see whether they feel the same way about the Tea Party as well.

ABERNETHY: And back on this question of tone, everything perhaps is going to be made more dramatic by the fact that it’s going to be, this year, the tenth anniversary of 9/11.

LAWTON: It’s hard to believe that it was almost 10 years ago when those attacks happened and that really did set up a lot of difficult issues for us as a country, both in terms of the war and as well as in terms of interfaith relations. I know a lot of Muslim groups are sort of bracing after seeing in the previous year a lot of protests against mosques and things of that nature. They’re concerned about the atmosphere and a lot of Muslims I’m talking with are worried about what’s going to happen leading up to the 9/11 anniversary.

ABERNETHY: But Kevin, you or E.J. have made the point that we have this real problem of trying to deal with homegrown terrorism and terrorism here that just emerges out of the suburbs some place, and on the other hand protecting the civil rights of a whole group of people.

ECKSTROM: This is a huge challenge for American Muslims and one of the big debates within the American Muslim community right now is how much do they cooperate with law enforcement on trying to prevent these sorts of attacks that nobody wants to see? How much should parents report their kids if they’re acting strangely or going to bad Web sites or talking in radical terms? And there’s a lot of Muslims who are afraid of being entrapped by the FBI and being led into plots that they might not otherwise do. But then they also know that if they don’t report them nobody else is going to and if there’s an attack, things are only going to get worse.

DIONNE: You’ve got tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of Muslims living in American suburbs, living middle-class lives, and if one or two or three or five of those thousands of kids is discovered to get involved in terrorism, suddenly we’re talking about these very middle-class, classically American places being breeding grounds for terrorism. I think one thing that is going to sort encourage that is if we make this big American Muslim middle class feel excluded from the rest of us, and we’re really going to have to think that through. Of course we don’t want home-grown terrorism, but we’re nowhere like where the Europeans are, because we have this great tradition of upward mobility and inclusion in our country.

DIONNE: You’ve got tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of Muslims living in American suburbs, living middle-class lives, and if one or two or three or five of those thousands of kids is discovered to get involved in terrorism, suddenly we’re talking about these very middle-class, classically American places being breeding grounds for terrorism. I think one thing that is going to sort encourage that is if we make this big American Muslim middle class feel excluded from the rest of us, and we’re really going to have to think that through. Of course we don’t want home-grown terrorism, but we’re nowhere like where the Europeans are, because we have this great tradition of upward mobility and inclusion in our country.

LAWTON: And this has been a challenge for American Muslims themselves within their communities. If we launch programs to combat homegrown terrorism, homegrown extremism, if we launch programs in our mosques, does that appear like we’re giving in to the stereotype that all Muslims are potential terrorists, and so they’ve really struggled within their community how to approach this problem. They want to look proactive. They want to look like they’re addressing this as good, loyal Americans, but how do you do that without giving into the perception?

ABERNETHY: Kevin, what do you expect to happen with the cultural center/mosque near Ground Zero?

ECKSTROM: Well, it’s going to be a challenge. They presumably have all of the zoning things that they need. They’ve got their permits and the city is going to allow them to build it. What they’re missing right now is the money. And it’s going to take them a while to raise as much money as they’re going to need, but it’s also going to be difficult to get, I think, a lot of people to support that because that center is so radioactive and it’s generated so much heat that there’s going to be a lot of people who maybe don’t want their names associated with it. And on the flip side, there’s a lot of Americans who don’t want the money coming from some foreign anonymous donor somewhere, so they have a big challenge there.

ABERNETHY: Now you were referring earlier to the fact that the beginning of 2011 may well seem like the beginning of the election campaign of 2012, E.J.

DIONNE: Right, and I think you’re going to see some sort of interesting positioning inside the Republican Party. I mean, we still don’t know if Sarah Palin is or is not going to run for president. Sarah Palin seems to be more representative of the Tea Party side of the right, although she has clearly some Christian conservative support. Mike Huckabee is going to be competing with her as the spokesperson for Christian conservatives, but every Republican running for president wants a piece of that vote, because it is such an important vote in the Republican primaries, and that’s going to start right now. It’s already started, before the show went on the air.

DIONNE: Right, and I think you’re going to see some sort of interesting positioning inside the Republican Party. I mean, we still don’t know if Sarah Palin is or is not going to run for president. Sarah Palin seems to be more representative of the Tea Party side of the right, although she has clearly some Christian conservative support. Mike Huckabee is going to be competing with her as the spokesperson for Christian conservatives, but every Republican running for president wants a piece of that vote, because it is such an important vote in the Republican primaries, and that’s going to start right now. It’s already started, before the show went on the air.

ECKSTROM: And I think something worth watching there is Mitt Romney, who is at the front of a lot of these polls, these straw polls, whether or not he tries to make the case about his Mormon faith again with the evangelical base. A lot of people say, you know, he did that; he doesn’t need to do it again. Other people say that he’s never going to win them over; there’s a certain amount of the base that’s just never going to accept a Mormon candidate. So I think it will be interesting to watch how he navigates the Mormon question.

ABERNETHY: And meanwhile, E.J., every pundit worth his salt is giving Obama advice about what he needs to do, how he needs to change himself, how he needs to change his language. Talk about that.

DIONNE: Well, the range of advice goes from you must be nicer to the Republicans and look like you’re a centrist to you’re political and moral obligation is to confront these guys and have a big argument so that the issues can be clear to the country. And I think he’s going to try to do a little of the former to say I’ve reached out my hand to them, and when the hand is rejected on certain issues, he’s going to flip to the second. But I think one of the things to look for is whether he does speak more in a moral and spiritual language both about himself and the underpinnings of his policies, but also about this sense of America can grab its position in the world back after a period when Americans felt we were in decline. I think there’s going to be some John Kennedy-esque rhetoric coming out him getting the country moving again in the coming year.

LAWTON: And the Democratic Party is going to have to figure out what it wants to do in terms of faith-based outreach. There was a lot of criticism from Democrats about how the party handled that in the last midterm elections and a lot of faith-based moderates and liberals and even some conservatives that don’t consider themselves Republicans felt that the party didn’t do enough to reach out to them, so that’s going to be something they’re trying to figure out as well.

ABERNETHY: Meanwhile the troop withdrawal from Afghanistan is supposed to begin n 2011. What are your expectations there?

ABERNETHY: Meanwhile the troop withdrawal from Afghanistan is supposed to begin n 2011. What are your expectations there?

LAWTON: Well, there’s some really difficult ethical debates still lingering in terms of what America leaves behind in Iraq and Afghanistan in terms of civil society and …

ABERNETHY: And safety and protection for the people who helped us.

LAWTON: Exactly. Religious minorities and people who were seen as being part of the American offensive—what’s going on with them and what responsibility does America have within that? And those are going to be difficult questions. I’ve been surprised how little the religious community has been focusing on these issues of war. It seemed like last year, in the last election, people just didn’t really talk about those ethical, moral issues.

ECKSTROM: And, you know, we’ve heard a lot of talk about the president’s problem with his base—you know, the liberal base is dissatisfied for any number of reasons. But it’s worth remembering that a good chunk of that base voted for him because he said he was going to close Guantanamo Bay, and it’s still open, and that he said he’d get us out of Afghanistan, and he actually sent more troops in. So there’s, I think, some ethical problems that he faces in terms of not moving fast enough on that issue.

DIONNE: Actually, he said he’d get us out of Iraq, and he said Afghanistan was the good war, and we’ll presumably continue to pull out of Iraq. My hunch is that if we have a withdrawal this year from Afghanistan it’s going to be very small. It’s clear that the new timeline that the administration wants seems to be 2014. And there’s going to be some opposition in his own party to not withdrawing more quickly. I also think some of the new conservatives who are less interventionist in Congress may also be a surprising opposition to a long commitment there.

ABERNETHY: Let me ask you to look at Europe and the Vatican. What do you expect there in terms of this ongoing struggle about the sex abuse of kids by priests? Anybody?

DIONNE: Everyone is silent.

ECKSTROM: Happy topic. Well, this pope has the unfortunate possibility of his legacy being presiding over this sex abuse scandal that reared its ugly head—that the church didn’t learn anything from the first time around. And I think he has made some progress in sort of admitting that the church needs to do some introspection and figure out what went wrong so that we don’t make this happen again. But the pope is going to be 84 in 2011. I don’t know how much more time he has left in that job, but probably a few years, and I think he’s going to be doing some legacy-making, because this is now at the point where he can still do some things and see what happens.

ECKSTROM: Happy topic. Well, this pope has the unfortunate possibility of his legacy being presiding over this sex abuse scandal that reared its ugly head—that the church didn’t learn anything from the first time around. And I think he has made some progress in sort of admitting that the church needs to do some introspection and figure out what went wrong so that we don’t make this happen again. But the pope is going to be 84 in 2011. I don’t know how much more time he has left in that job, but probably a few years, and I think he’s going to be doing some legacy-making, because this is now at the point where he can still do some things and see what happens.

LAWTON: Well, so many people in the church are frustrated because they want to get beyond this issue but they just can’t do it, and so that’s been something they’ve all had to confront.

DIONNE: I think it’s sort of an argument between people who defend the Vatican and the church say look, they understand, they’ve tried to fix this, they’ve made some moves versus others who say that they still haven’t fully taken responsibility for changing the structures of the church. It’s a classic argument between more conservative or traditionalist people and people looking for greater change in the church because they think it needs it, and I think that is an ongoing struggle and that the sex abuse scandal is a piece of that larger struggle.

ABERNETHY: Our time is almost up, but before we quit, in this coming year do you see something happening or that might happen or do you see some person that you’re going to be paying particular attention to?

LAWTON: Well, we should also point out that last year a lot of the things we discussed we didn’t predict. So, as E.J. said, it’s hard to know that. I think it is going to be a pivotal year for religious groups and issues surrounding homosexuality, whether we’re talking court cases around gay marriage or whether we’re talking denominations still really struggling over how to handle gay clergy and gay bishops. And the Anglican Communion, which has really been torn about by this subject, is also going to have to face some tough questions this coming year.

ECKSTROM: I’m going to keep an eye on Archbishop Tim Dolan in New York, who is the new president of the Catholic bishops conference. He’s a media-savvy guy, he gives you a bear hug, he’s sort of a telegenic face for the church. But he’s no shrinking violet. He will take on the issues of the day, but in sort of a friendly kind of way. It will be interesting. The only real power he has is the power of the megaphone, and which issues he chooses for the bishops to emphasize.

DIONNE: I think that’s an excellent selection. I would say if I could combine Palin, Huckabee, Obama, Romney—we’re going to see if the nature of the discussion of religion in our politics changes substantially this year or not. As we’ve already said, there are challenges to each of those figures, and it will be interesting to see how they deal with it.

ABERNETHY: I have been wondering with respect to Iraq and now Afghanistan why there was no peace movement—not more of a peace movement. Do you think with Afghanistan, as we begin to come out of there, that there will be such a thing?

DIONNE: I think going into Afghanistan there was very broad support when we started because many people, except for pacifists and a few others who have legitimate reasons for opposing all war, most people thought this was kind of a just war response, so you didn’t have a big opposition. I think now a lot of people say God, this is a terrible mess. I don’t have a good answer coming out of it, and I think that sort of undercuts what might otherwise be a big peace movement.

ABERNETHY: Thanks, E.J., our time is up. Many thanks to Kim Lawton of Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, Kevin Eckstrom of Religion News Service, and E.J. Dionne of the Brookings Institution. That’s our program for now. I’m Bob Abernethy.