In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Moral Questions and Military Intervention

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: In justifying last month’s military intervention in Libya, President Obama used solely humanitarian reasons, saying the US was acting to prevent a massacre of innocent civilians.

President Barack Obama (from March 28, 2011 speech): Some nations may be able to turn a blind eye to atrocities in other countries. The United States of America is different.

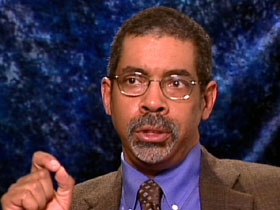

LAWTON: According to prominent Yale Law School professor Stephen Carter, this marks a significant moral shift in America’s use of force.

PROFESSOR STEPHEN CARTER (Yale Law School): President Obama, unlike his recent predecessors, has taken the position that one of the things the American military will do in the world is intervene to protect people who are being slaughtered by their own government, and that’s an enormous break with America’s practice.

LAWTON: In previous conflicts, including the first Gulf War and air strikes in the Balkans, US presidents argued that while humanitarian factors may have also been at play, military action was in America’s strategic interests.

CARTER: The argument that is being offered for Libya is entirely the argument that we have no self-interest here except to protect these people who are going to be slaughtered. Now I know a lot of people think, “Well there’s something else going on, there’s really another reason.” Who knows? All that could be true, but what’s really interesting is that the language the White House is using is entirely the language of humanitarian intervention.

CARTER: The argument that is being offered for Libya is entirely the argument that we have no self-interest here except to protect these people who are going to be slaughtered. Now I know a lot of people think, “Well there’s something else going on, there’s really another reason.” Who knows? All that could be true, but what’s really interesting is that the language the White House is using is entirely the language of humanitarian intervention.

LAWTON: Carter has a new book called The Violence of Peace: America’s Wars in the Age of Obama. He claims the man many voters considered the “peace candidate” has turned into a “war president” with an expanding philosophy about the use of force. Carter says that philosophy was signaled in Obama’s 2009 acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize.

President Barack Obama (from 2009 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech): Inaction tears at our conscience and can lead to more costly intervention later. That’s why all responsible nations must embrace the role that militaries with a clear mandate can play to keep the peace.

CARTER: What’s striking about the war in Libya, whether one is for it or against it, is that it shows that President Obama was serious, that he actually meant what he said, that he actually believes that’s a justified use of American power.

LAWTON: Carter asserts that Saint Augustine and other early developers of the just war theory supported the idea of using force to achieve justice.

CARTER: Today we look at self-defense as the axiomatic case where everyone agrees that’s when you can go to war. For the early thinkers that was one of the weakest cases, because as Augustine liked to say, “You should never go to war out of love for yourself but only out of love for others.”

CARTER: Today we look at self-defense as the axiomatic case where everyone agrees that’s when you can go to war. For the early thinkers that was one of the weakest cases, because as Augustine liked to say, “You should never go to war out of love for yourself but only out of love for others.”

LAWTON: The price of inaction, Carter says, can indeed be terribly high, as was the case in Rwanda when nearly a million people were killed in the 1994 genocide. The US did not intervene there.

CARTER: President Clinton later said that was the greatest failure of his presidency, and I think it’s absolutely right. I think it was a grave moral mistake by the country that is not only the leader of the free world but also the preeminent military power in the world.

LAWTON: How do you morally weigh Libya versus Darfur?

CARTER: What I think the administration has not done successfully in Libya is made the case about why, if you’re going to make a humanitarian intervention, this is the place to do it. There are places in the world that cry out for military intervention. Darfur is the most obvious of those, where you have had a genocide go on for a long period of time. Successive presidents have chosen not to go to Darfur. Why Libya? Why not Bahrain? Why not Yemen?

LAWTON: Carter says the administration should make public the intelligence it acted upon.

CARTER: It’s important that it try to explain to the American people and to the world why it was so certain that atrocities would be committed unless the West intervened quickly.

LAWTON: And Carter asserts the American public also has a responsibility in determining what things are worth killing for—and dying for.

CARTER: We need to develop a moral language, an ability to talk about war because it’s so very important—talk about war without regard to party or country but rather in the sense of what’s fundamentally right or wrong. What is it that, in a just society and just world, force should ever be used for?

LAWTON: Carter believes the centuries-old just war theory is still the best place to begin.

CARTER: It supplies a vocabulary, a vocabulary that asks us to think, is there a just cause? Is this the last resort? Can the use of force actually do the thing that we claim we are setting out to do? And is our use of force proportional to the problem we are trying to solve? When we ask questions like that we’re asking moral questions. I think those are the right questions to ask.

LAWTON: And they are questions, he says, that will come up well beyond Libya.

I’m Kim Lawton reporting.