In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

James Carroll on Jerusalem

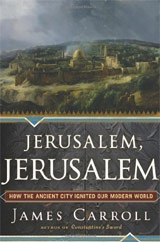

Read an excerpt from JERUSALEM, JERUSALEM by James Carroll

JAMES CARROLL (Author, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World”): Jerusalem in the ancient world was the cockpit of violence. It was the place where all the warring armies of the empires intersected.

Beginning with that first experience of exile in Babylon, Jews came into a new awareness of who they were and who their God was by looking back at Jerusalem, and they claim their identity by refusing to forget it.

Augustine was arguing for the survival of Jews as Jews in Christendom who would witness to the truth of Christian claims by their degradation, and that’s been the source of tremendous anti-Jewish and ultimately anti-Semitic behavior, contempt, and one of the most powerful forms of the degradation was the Jews are to be permanently in exile from Jerusalem, from the Jewish home.

It’s so important to emphasize that the Islamic arrival in Jerusalem was nonviolent and respectful of the Jewish tradition, so that when the caliph beheld the Temple Mount, which to him was to be revered because that was the place where God had stopped Abraham from sacrificing his son, he’s astounded to discover that the Christians have been treating it as a garbage dump, and the caliph, Umar, ordered the Temple Mount cleaned up, reverenced; he invited Jews back into the city who had been exiled by the Christians. Those first generations of Muslims were honoring the Jewish holy place without any sense of conflict with it, and we know that that was lost.

It’s so important to emphasize that the Islamic arrival in Jerusalem was nonviolent and respectful of the Jewish tradition, so that when the caliph beheld the Temple Mount, which to him was to be revered because that was the place where God had stopped Abraham from sacrificing his son, he’s astounded to discover that the Christians have been treating it as a garbage dump, and the caliph, Umar, ordered the Temple Mount cleaned up, reverenced; he invited Jews back into the city who had been exiled by the Christians. Those first generations of Muslims were honoring the Jewish holy place without any sense of conflict with it, and we know that that was lost.

In the year 1096 when the pope calls for the crusade to take Jerusalem back from the infidel who have been occupying it since the seventh century, it sears the European Christian imagination with violence, holy war, God wills violence, and it centers the Christian imagination on—guess what?—Jerusalem.

The return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem, to Israel, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries especially, culminating in the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, is a reversal of this ancient fate that was generated by the Romans and then theologized by the Christians. And I would just add that we Christians have been reckoning with this, and that’s the meaning for us Catholics of the tremendously important visit to Jerusalem by Pope John Paul II in the year 2000. He prayed at the Western Wall as a Jew would pray, without invoking Jesus, and he offered his act of repentance there—a tremendously important reversal of theology, the example of the kind of reckoning with the past that has to keep happening, actually.

Christians, Jews, and Muslims all have a sacred connection to it, each in a very different way. That sacred connection to this place, even though at the present moment it’s a source of contention, is actually a profound source of union.

I don’t see any hope for peace between Israelis and Palestinians until two things happen. One, Palestinians have to somehow reckon with the authentic return of the Jewish people to the Jewish homeland is a fulfillment of Jewish history. On the other side, I don’t see much hope for peace until Israelis reckon with their part in the dispossession of the Palestinian people, and in particular I’m troubled by the settlements and the ongoing occupation.

The holy one we all have in common is the one God, which makes us brothers and sisters, so the place itself is a source of peace, and so I love Jerusalem, including the mess of it—the Christian mess, certainly, but all of the messes of it.

EXCERPT: JERUSALEM, JERUSALEM

“The Most Absolute of Cities”

To speak of the hope of peace for Jerusalem is to acknowledge the enormous varieties of religious experience, to use the great phrase of William James, which in the twenty-first century face each other in the intimacy of the global village. Jerusalem is that village writ small, a living image of how all believers and nonbelievers inevitably encounter—or confront—one another as near neighbors, unable to avoid each other’s differences, and therefore unable not to be influenced by them. Jerusalem has long been the most absolute of cities, yet it is the capital today of encounters in which absolutisms are shown to be mutually interdependent, and therefore not absolute. Neither values nor revelations exist outside of history, and if Jerusalem does not show that, nothing does. Yet Jerusalem also shows how each religion that finds a home there, including “the religion of no religion,” understands itself as offering a comprehensive vision of the whole of reality, even if it does so from the necessarily partial perspective of its contingent tradition. The religions, while emphasizing the whole to which their revelation points, have tended to forget the inevitable partiality that arises from the basic fact of the human condition, that truth is always perceived from one point of view or another—never in itself.

That is what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel meant when he declared that “God is greater than religion.” Every religion. That might seem a modern insight, yet it encapsulates the breakthrough vision that the captive Jews were given in Babylon nearly three millennia ago, the vision that made Judaism the first of the three monotheisms. Those religions, like every religion, came into being with an inbuilt tendency to confuse themselves with the object of their devotion, as if the worshiped deity were the religion. Religious orthodoxies of every kind tend to forget that at their center is an unknown mystery—unknown because unknowable. “So what are we to say about God?” Augustine asked. “If you have fully grasped what you want to say, it isn’t God. If you have been able to comprehend it, you have comprehended something else instead of God.” Humans are restless in the face of what they cannot know, which is why the essential unknowability of God has prompted humans to make gods out of what we can and do know. Our selves, tribes, nations—and doctrinal beliefs. When religions substitute themselves for God, as they have done from the time of Jeremiah to the time of crusading popes to the time of fatwa-issuing ayatollahs, they become igniters of sacred violence, which, with its transcendent claims, can be more enflaming than any other fire, any fever.

The connection between religion and violence has been powerfully laid bare in the twenty-first century. How will its exposure shape the next generation of believers?

From “Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World” by James Carroll (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011)