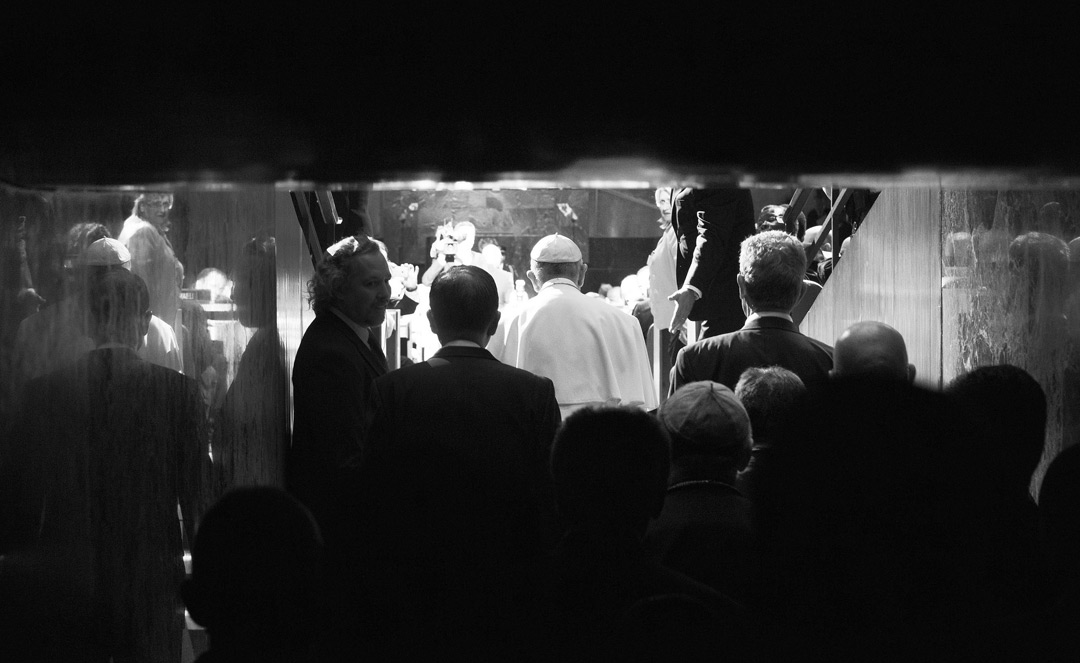

Photo: UN Photo/Evan Schneider

After his masterpiece of a speech before the United States Congress, Pope Francis laid down a dud today (September 25) in his speech before the United Nations. And there was a consequence to such a dud: He failed to make as persuasive a case as possible of his concern about climate change and the poor.

It’s hard to know what to make of the striking difference in substance and style between the two talks. The first was brimming with imagery, stories, and warmth; the second was philosophical, abstract, and scolding. The first confirmed everything we’ve come to know about Pope Francis; the second sounded like Pope Benedict Emeritus had come back for one final swan song blast. There’s little doubt that Pope Francis poured his heart and soul into the speech before Congress and left the UN talk to be shaped largely by aides.

Pope Benedict saw the great moral challenge of our time as the loss of a sense of absolute truth. Surging Prometheans that we are, there’s no boundary we won’t cross in our hubris to remake ourselves and our world. In a noted speech to the German parliament (which is quoted in Francis’s UN speech), Benedict described this tendency as a chosen blindness to the fact that we are not only spirit and will but also nature. This claim provides the logic by which Francis’s UN speech understands the abuses of power now besetting the world. Nations amassing power; financiers seeking piles of wealth; even gay men and lesbian women departing from the requirements of nature to enter into marriage: all of these examples proceed by way of radical self-will and the rejection of binding moral claims emerging from the structure of reality itself.

That’s a pretty abstract way of putting things. But Benedict approached the world in pretty abstract fashion. And, by contrast, we know that Francis does not. For him, the great moral challenge of our time is the loss of capacity for relationships with concrete and vulnerable human beings. We hear always from Francis a language that captures this central concern. He speaks often of care. He encourages the creation of a culture of encounter in which we come to know those far away. He speaks of all people as brothers and sisters. He discusses the problem of gay marriage not so much as a rejection of abstract nature as much as a failure of concrete relationships. He even speaks of our brotherhood and sisterhood with the natural world.

But this language of relationship played almost no role in the UN speech and, because it didn’t, Francis lost an opportunity to make a more persuasive case for the central concerns of his agenda. The UN speech sounded like the fading days of Benedict’s papacy: too many shopworn abstractions that put people off and aren’t capable anyway of capturing the dynamism of power relations on the international scene. By contrast, Francis’s rhetoric of relationship readily connects with people and captures much better, too, the way power actually works.

When he spoke to the political representatives of the American people, Francis sounded a persuasive, universal note. When he spoke to the assembly of the people of the world, he sounded like his sectarian predecessor.

David DeCosse directs the campus ethics programs at Santa Clara University.