In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Trayvon Martin Case: Racism, Violence, and Justice

BOB ABERNETHY, host: Second-degree murder charges were filed this week against George Zimmerman, the volunteer neighborhood watchman who shot and killed unarmed teenager, Trayvon Martin. The announcement came after weeks of protests demanding Zimmerman’s arrest. Several religious groups also called for an investigation into Martin’s death. Recent polls show that attitudes about the case vary dramatically by race.

Joining me with more on this are Kim Lawton, managing editor of this program, and Harold Dean Trulear, associate professor of applied theology at Howard University in Washington, DC and national director of the Healing Communities Prisoner Reentry Initiative.

Professor, welcome, we’re glad to have you here again.

PROFESSOR HAROLD DEAN TRULEAR (Howard University Divinity School): Thank you. It’s my privilege.

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: Good to see you again.

ABERNETHY: The contrast in the way people saw this case in Florida just couldn’t have been more stark—overwhelming differences in the way whites and blacks saw it and what they saw in it. How did you see it?

TRULEAR: I identified with it. I have two sons. They’re grown. When they were teenagers, part of their training in learning how to drive was what to do when you’re pulled over by the police so you don’t end up being a statistic. And I think for a number of African Americans the facts of the case as they’ve come out and as some of the speculation has gone—it just fits so closely to a lot of our experience, even whether we’re poor, whether we’re middle class.

LAWTON: And that sense of continuing injustice. It seemed like this really pricked those feelings.

TRULEAR: Yeah, I think it did, and that’s why you see the level of emotion, I believe, that’s coming out. We recognize this. We’ve seen this before in some—various ways, shapes, or forms.

ABERNETHY: And beyond this, beyond the, what do you call it, the outrage about racial injustice, beyond that is something more that you see, that you’ve been working on—the question of violence.

TRULEAR: Absolutely. We live in a violent nation. We settle conflicts through violence. Things escalate. This case is a perfect example of an initial confrontation escalating into a violent conclusion. Those types of things happen all the time, and we’ve lost our ability to be civil about discussion and disagreement. The number one cause for homicides in this country is arguments. it’s not drugs on the street, it’s not other things like that. It’s conflict.

ABERNETHY: But is that racism or is it black on black?

TRULEAR: Most of it, in terms of homicide, is black on black. I think that both racism fits the mold, and then also the way in which African-American males have turned on each other. Trayvon Martin was fourteen times more likely to have been killed by Trayvon Martin than he was George Zimmerman.

LAWTON: But that’s a very provocative statement, and I am wondering what kind of reactions you get within the African American community when you say something like that.

TRULEAR: You get a negative reaction when you do it, by making it either one case or the other. What we’re trying to do, those of us that are working on this issue, is trying to say let’s expand the conversation. Both situations are unacceptable, being killed by another African American male or being killed by a non-black town watchman. They’re both unacceptable, and we need to be working on violence reduction in all cases.

LAWTON: And within the faith community, what resources do you see there to help in this?

TRULEAR: Well, there are a number of models that have been going around the country. The most important thing is getting out on the streets and building relationships, developing the kind of community where people get to know each other and begin to learn how to resolve conflict. You’ve seen it in Boston through the Ten Point Coalition over the years. This new program, well it’s not so new now, but Operation Ceasefire that’s come out of Chicago. It’s not a faith-based program but there are a number of people of faith who are involved in it, and they’re all focusing on resolving conflict through means that are other than violent.

ABERNETHY: But that’s something, I would guess, that is uniquely done by blacks in black neighborhoods. You don’t see a role there for whites, do you?

TRULEAR: Oh, absolutely.

ABERNETHY: Do you really?

TRULEAR: Oh, yeah. In fact, one of the top people who is doing violence reduction in Boston was a native Israeli who had fought in the Israeli army. What gets valued is not color, it’s the fact that you are real, and that you’re present, and I know that there are white people who have done successful work in anti-gang strategies, anti-violence initiatives. It can cross color lines.

ABERNETHY: But do you want people in churches to go out into the violent neighborhoods and build relationships?

TRULEAR: They already have those relationships. We are—those are our sons, those are our grandsons, those are our daughters. So for me, it’s not a matter of going into a neighborhood. We’re already located there. We already have connections there.

ABERNETHY: Well, thank you very much and good luck in all that work that you are doing.

TRULEAR: Thank you.

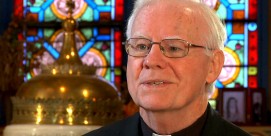

ABERNEHTY: Professor Harold Dean Trulear of Howard University in Washington, DC.