Eco-faith

BOB ABERNETHY: Now, the greening of religion. Many of us probably overlooked this year’s observance of Earth Day last Thursday, the day set aside for reaffirming a commitment to protecting the environment. Not so for many churches, mosques, and synagogues. In recent years, because of a shift in thinking about the natural world, many faith communities have been taking up the cause of the environment. This movement is particularly strong along the banks of the Columbia River, where salmon has been declared an endangered species. Reuben Martinez has been there.

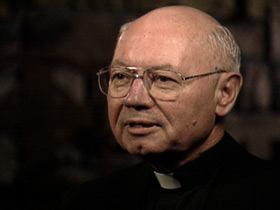

REUBEN MARTINEZ: The Columbia River courses 1,200 miles across some of the Pacific Northwest’s most beautiful country, a land that has also been mercilessly exploited for its natural resources. But for the people who live along the river, its waters have a deeper meaning. Bishop William Skylstad of the diocese of Spokane grew up on an apple farm near one of the Columbia’s countless tributaries.

Bishop WILLIAM SKYLSTAD (Diocese of Spokane): The river for us was a place to see wildlife; it was a place to see the ducks, certainly in the summer and the fall months, the salmon migrating up the river. The river meant a lot to us.

MARTINEZ: For millennia, the Columbia’s waters sustained the physical and spiritual life of native peoples in the region. Like the bishop, Umatilla leader Armand Minthorn’s childhood was dominated by the river.

Mr. ARMAND MINTHORN (Umatilla Tribe): You know, I hear a lot of our older people talk about when they were growing up, and they talked about this river, and they talked about the salmon runs and how plentiful they were. That’s how it was then, before the dams.

MARTINEZ: Massive dams like the Grand Coulee harnessed the river for irrigation and power, but they have also spelled disaster for the salmon and the river. The Columbia has been polluted by chemical runoff from mines and farms, its tributaries muddied by erosion from logging and overgrazing. The river now faces an environmental crisis that has stirred communities of faith, giving rise to an environmental movement rooted in spiritual rather than secular traditions.

Practically every mile of the mighty Columbia has known human intervention. It was the profaning of these waters that gave birth to this spiritualized environmentalism. But if there’s one symbol of the sacred that unites communities of faith, it’s the waters that give life.

Mr. PAUL GORMAN (National Religious Partnership for the Environment): We affirm that the Earth, with its salmon, are yours.

MARTINEZ: At this crossroads of politics and faith, theology is being rewritten. The Old Testament talks about man’s dominion over nature. But many religious leaders around the country now talk about stewardship, mankind’s responsibility to protect God’s creation.

Mr. GORMAN: This is a coming to awareness of civilization and of the faith community more particularly of what it means to be here and human and in right relationship with creation.

Bishop SKYLSTAD: For us, the Church, I think an important role is to reflect in ethical ways about the environment and what’s happening in our environment. How can we help the land continue to be fertile? How can we help the river system continue to be a fertile place, so to speak, so that the salmon species will continue to survive, so that agriculture in our area will continue to be a sustainable agriculture?

MARTINEZ: The boy who once swam in the river is now a Catholic bishop. He has been traveling the Columbia basin for the past year, together with his fellow bishops from the Pacific Northwest and Canada, investigating the river and its problems.

Unidentified Man #1: If you look below us on the right, you see some of the early farms here. This is Sagemoor Farms, one of the older ones …

MARTINEZ: This trip is leading up to an unprecedented pastoral letter the bishops plan to issue next year, calling on people of faith to join in saving the river’s ecosystem.

Man #1: You’re seeing here some of the nuclear-related complexes.

MARTINEZ: A big concern is the now-inactive Hanford Nuclear Reservation, which produced plutonium for the atomic bomb during World War II. Leaking radioactive storage tanks now threaten nearby waters and land.

Mr. PETER ILLYN (Target Earth): We have to begin doing business differently in our relation ship to the Earth. And we have a saying: “Extinction isn’t stewardship.” And so we really draw a line in the sand and say there’s a point where we — you know, where we reach a crisis. And I think we’re there. This is the Columbia River. We go up to Indian Heaven Wilderness.

MARTINEZ: At the other end of the Columbia River near Portland, and at the other end of the Christian spectrum, another faith-based project is under way.

Mr. ILLYN: And then this whole area here is wilderness. This is 12 Heartbeat Rule.

MARTINEZ: Peter Illyn, a former evangelical minister, runs the Pacific Northwest office of Target Earth, a nationwide evangelical group that does grassroots organizing and environmental education.

Mr. ILLYN: “And God said, ‘Let the water teem with living creatures, and let the birds fly above the Earth, across the expanse of the sky.'”

MARTINEZ: On this day, Target Earth has gathered a group of Christians to restore and protect vegetation on the banks of the Lewis River, a tributary of the Columbia where erosion from cattle grazing has silted the waters, a potential danger to salmon runs.

Mr. ILLYN: Tell me what’s happening here.

Unidentified Man #2: Well, what’s happened so — is the river has been basically coming out of there and heading right for this area, and it’s been eroding very badly.

Mr. ILLYN: People take care of what they love, and they love what they know. So really, it’s –it’s to connect people back to the Earth and to do it within the context of their faith, that they’re called to be stewards; they’re called to be caretakers.

MARTINEZ: The communities along the river are polarized. Those who make their living from the river’s waters — the farmers, the irrigators, the barge operators — are outraged at the proposal to reroute the river around four dams on one of the Columbia’s tributaries. Environmentalists say this breaching of the dams is crucial to restoring the salmon run.

Bishop SKYLSTAD: As you can see, this is a very complex area, but …

MARTINEZ: Seeking consensus rather than confrontation, Bishop Skylstad has held several town hall-like meetings up and down the Columbia, hearing from all parties for whom the river is a lifeline.

Mr. FRED IZIARI (Eastern Oregon Irrigation Association): And let’s not make any mistake about it. You want to take the dams out, you’ve got to take the farmers with it. There’s nothing that’s going to be left, nothing.

Mr. JIM TIMMONS (Environmentalist): Is that your view? Well, it seems to me that basically what we’re looking at here is an increase in cost of operation of getting that water up there. And we might find ourselves here in a few years where the dams — say we decide to keep the dams, and that fish go — are exterminated.

Bishop SKYLSTAD: There are so many competing interests, and yet we hope that this pastoral letter will foster a sense of civil dialogue as society strives to make prudent, wise decisions as we look to the future.

Mr. ILLYN: I think it’s gonna be a bit ugly, that they’ll be — the politics are gonna increase. And that’s why we’re so dedicated to — to standing up and reminding at least the Christians involved in the process that the moral aspect of how we treat the Earth is — is more important than the political and the economic. This is probably the most important moral issue facing the rest of human history.

MARTINEZ: Will the increasing involvement of faith-based communities and environmental politics bolster a movement that has long been seen as the domain of tree-hugging radicals? The moral authority that churches bring to these issues is certainly a force to be reckoned with. The question is whether the new green gospel can inspire people beyond their self-interest for the sake of a sustainable relationship between man and nature. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Reuben Martinez on the Columbia River.