In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Holocaust Remembrance

Read an excerpt from THE EICHMANN TRIAL by Deborah Lipstadt

DEBORAH LIPSTADT (Professor of Modern Jewish History and Holocaust Studies at Emory University and Author of The Eichmann Trial): The trials that took place immediately after the war were based primarily on documents. In the Eichmann trial, Gideon Hausner, the attorney general, made a decision to call the victims of genocide. He called these witnesses to tell their personal stories, and they told their stories one by one by one. So people began to associate what happened during the Holocaust, the Final Solution, with specific people, and in that way it put a human face on genocide.

The victims had spoken before, but they had never had an audience the way they had it at the Eichmann trial. The world was listening. I think it was the impact of the intensity, the idea of being in a courtroom setting, that the perpetrator was sitting there in that glass booth—I think all those things together gave what the victims were saying, what the stories they were telling, an added authenticity and authority.

The victims had spoken before, but they had never had an audience the way they had it at the Eichmann trial. The world was listening. I think it was the impact of the intensity, the idea of being in a courtroom setting, that the perpetrator was sitting there in that glass booth—I think all those things together gave what the victims were saying, what the stories they were telling, an added authenticity and authority.

People understood that these people weren’t inherently flawed, that they weren’t inherently weak, but that they were in a sea of opposition, a sea of hostility, and there was no one, no one there to help them.

When you begin to hear the story from people, when it becomes personalized, when you hear it in the first person singular, “This is my story and this is what happened to me,” genocide takes on a new meaning. You begin to realize that it didn’t happen to just a group of nameless people, but it happened to individuals, and what happened is their memory, and then the memory gets transmitted to the next generation.

It’s a lesson to the world of what happens when you stand silently by. In fact, it’s more important that the rest of the world, those people who aren’t associated with the victims, know about it. That’s what it means to be persecuted, that’s what it means to be a victim, that’s what it means to call for help and have nobody answer. That’s the importance of memory—that you take this memory, integrate them into ourselves, internalize them, and act on that in our lives.

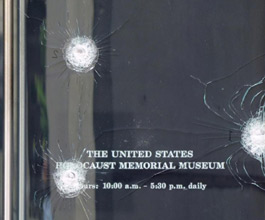

I was here as a scholar in residence at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and then on June 10, [2009] as I was on my way downstairs to give a lecture to a group of people who had come to visit the museum, I passed the guard station. I saw Officer Johns and the other officers greeting people. No sooner had I gotten to the room, a few minutes thereafter shots rang out, and it was an 88-year-old Holocaust denier, racist, anti-Semite who came to the museum, approached the door. Officer Johns reached out to open the door to let the man in, and the man took out a rifle and shot him. It happened because this killer was motivated by hatred, was motivated by anti-Semitism, was motivated by exactly those sentiments which this museum is dedicated to fighting, and it was such a terrible irony.

I was here as a scholar in residence at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and then on June 10, [2009] as I was on my way downstairs to give a lecture to a group of people who had come to visit the museum, I passed the guard station. I saw Officer Johns and the other officers greeting people. No sooner had I gotten to the room, a few minutes thereafter shots rang out, and it was an 88-year-old Holocaust denier, racist, anti-Semite who came to the museum, approached the door. Officer Johns reached out to open the door to let the man in, and the man took out a rifle and shot him. It happened because this killer was motivated by hatred, was motivated by anti-Semitism, was motivated by exactly those sentiments which this museum is dedicated to fighting, and it was such a terrible irony.

On this Yom HaShoah I think it’s very important for the world to remember that evil begins with a single individual talking to another individual talking to another individual. Maybe they are motivated, as was the case in the Holocaust, by an age-old hatred, but it takes one person with another person with another person to make it happen, and that each of us as individuals have the power to say, “Stop.” We may not be able to stop the hatred, but we can say, “Stop, I won’t be involved in it.” We also have to remember not to think of the victims only as “the six million,” but they were one by one by one, and in that courtroom in Jerusalem 50 years ago people heard the voices of those victims in a way that they hadn’t heard them before.

EXCERPT: THE EICHMANN TRIAL

“Testimony Riddled with Pain”

Shortly thereafter, the leader of the Vilna resistance fighters, Abba Kovner, testified. In December 1942, he had called for active resistance against the Nazis. This was probably the first such call in all of Europe. In it, he used a phrase that subsequently was used colloquially as a means of denigrating the victims: “Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter.” After leading the Vilna uprising, he joined a Soviet resistance group. He subsequently became a kibbutznik and one of Israel’s leading poets. As a man of the land, arms, and letters, he epitomized the “new Jew.” Yet his testimony was riddled with pain. He told of his student Tsherna Morgenstern, a “tall upstanding girl” with “wonderful eyes,” who was taken with her classmates to Ponary. An SS officer ordered her to step forward: “Don’t you want to live—you are so beautiful….It would be a pity to bury such beauty in the ground. Walk, but don’t look backwards.” As she waked away, her classmates watched with envy until the officer shot her in the back. Kovner told all this and more. Toward the end of his speech—it was more that than anything resembling testimony—he turned to the judges and declared, “A question is hanging over us here in this courtroom: How was it that they did not revolt?” As a “fighting Jew,” he would “protest with all my strength” if someone asked that question with even “a vestige of accusation.” In fact, rather than question why most Jews did not rise up, people should recognize that not resisting was the rational thing to do. Resistance organizations are created by calls from a “national authority.” There was no Jewish authority to issue that call. There was no one to organize an uprising. Rather than demean the victims, contemporary generations should recognize how “astonishing” it was that “there was a revolt. That is what was not rational.” Kovner’s words, together with [Moshe] Beisky’s earlier testimony, constitute eloquent responses to a question that people who live privileged and secure lives seemed to have few compunctions about asking.

From “The Eichmann Trial” by Deborah E. Lipstadt (Schocken Books, 2011)