In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Path to Sainthood

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: Saints have been part of the Roman Catholic Church for centuries as heroes, patrons, intercessors and spiritual companions. But the path to sainthood is never an easy one.

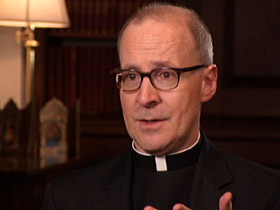

REV. JAMES MARTIN, S.J. (Author, My Life with the Saints): The lives of the saints show us that, you know, God makes holiness out of all sorts of different materials.

LAWTON: Many religious traditions honor people who are considered especially holy. But the Catholic Church has a uniquely complex system for declaring someone a saint. It’s a multistep canonization process that has evolved since the thirteenth century. Father James Martin is author of the book My Life with the Saints.

MARTIN: The Catholic Church has a more complicated process than anyone else on almost any topic, basically. I think it’s important for people to know that when we hold up someone for public veneration, or as an example, that their life has been thoroughly investigated.

LAWTON: The process usually begins in the region where the potential saint lived or is buried. After local Catholics show a particular devotion to the person, the bishop opens an investigation into the case or “cause” for sainthood. A point person called a postulator oversees the cause. According to the rules, there should be a five-year waiting period after the person’s death. But in the cases of both John Paul II and Mother Teresa, that waiting period was waived.

LAWTON: The process usually begins in the region where the potential saint lived or is buried. After local Catholics show a particular devotion to the person, the bishop opens an investigation into the case or “cause” for sainthood. A point person called a postulator oversees the cause. According to the rules, there should be a five-year waiting period after the person’s death. But in the cases of both John Paul II and Mother Teresa, that waiting period was waived.

MARTIN: Some people have argued, you know, why rush them? You know, what’s the rush? I mean, they’ll be a saint in ten years, or 20 years, or 30 years, so why not let the process sort of go its normal route? On the other hand, people say, “Well, you know, the pope is responding to the desires of the people,” which is what people always want the Vatican to do.

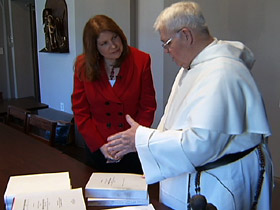

LAWTON: At the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C., Father Gabriel O’Donnell is a postulator. He actually went to postulator school at the Vatican. O’Donnell shepherded the cause for Father Michael McGivney, founder of the Knights of Columbus. That cause has advanced several stages in the process. O’Donnell has now begun work on a new cause for Rose Hawthorne, the daughter of nineteenth-century author Nathaniel Hawthorne. She cared for low-income cancer patients.

REV. GABRIEL O’DONNELL, O.P. (Dominican House of Studies): The first thing you have to do is research anything the person has written or published, and then you begin studying anything they have left behind in terms of documentation.

REV. GABRIEL O’DONNELL, O.P. (Dominican House of Studies): The first thing you have to do is research anything the person has written or published, and then you begin studying anything they have left behind in terms of documentation.

LAWTON: It can be a tedious, arduous process, which includes interviewing people who knew the potential saint or were affected by his or her work. The church teaches that in order to be a saint, someone must have lived a life of “heroic virtue.”

MARTIN: A life of holiness, basically, a life of charity, Christian charity and love, service to the poor often, but, you know, the person has to be holy on a personal level beyond just doing, you know, great deeds, beyond just founding a religious order or being pope or something like that.

O’DONNELL: But you’re also looking for the flaws, because the whole idea of the saint is that they’ve overcome their difficulties, you know, not that they didn’t have any. One of the things that the church is very strong about is that if you can find anything negative you have to make that known.

LAWTON: There even used to be an official role for someone to argue against the cause. It was known as “the devil’s advocate,” although the position was eliminated in 1983. The evidence, usually thousands of pages, must be assembled according to the Vatican’s strict set of guidelines or norms.

O’DONNELL: Page after page of norms and you have to follow each step carefully. If you miss a step the whole thing can be thrown out as invalid, and it’s happened to some causes.

O’DONNELL: Page after page of norms and you have to follow each step carefully. If you miss a step the whole thing can be thrown out as invalid, and it’s happened to some causes.

LAWTON: If the evidence is approved, the person is declared “venerable”—worthy of consideration. A special Vatican office, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, takes over the cause, and the search begins for a miracle attributed to the intercession of the potential saint after his or her death. In Catholic teaching, the miracle is confirmation that the person is indeed in heaven.

O’DONNELL: The point of the miracle which fascinates many people but also puzzles them is that if the church is going to declare this person to be blessed or a saint, the church is looking for some sign from God, so it’s what we call the “digitus dei” or the finger of God says yeah.

LAWTON: Any reported miracles are subjected to rigorous review by a panel of scientists and doctors.

MARTIN: The Vatican’s bar is very high. So the miracle, which is usually a medical miracle or a healing, must be instantaneous, right? It must be non-recurring. It must be not attributable to any other treatment, basically, and it must just be the result of praying to that one saint, so—and it must be medically verifiable. The doctors and scientists basically don’t say this is a miracle or not. They say to the Vatican, “This is inexplicable.”

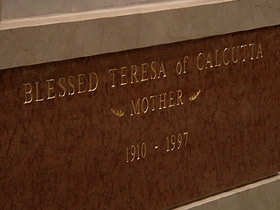

LAWTON: It’s up to the pope to declare it a miracle, and if he does so, the person is eligible for beatification, although martyrs—those who died for the faith–may be beatified without a verified miracle. In beatification, the person is given the title “Blessed.”

LAWTON: It’s up to the pope to declare it a miracle, and if he does so, the person is eligible for beatification, although martyrs—those who died for the faith–may be beatified without a verified miracle. In beatification, the person is given the title “Blessed.”

MARTIN: It’s a recognition of the person’s holiness and importance for the worldwide Church, and of course canonization is a much more sort of broad stamp of approval by the Church. But even “blessed”—I mean someone like Blessed Mother Teresa, you know, is already being venerated worldwide, as she was in her lifetime.

LAWTON: For a declaration of sainthood a second miracle must be verified, and it must have taken place after beatification. That can take many more years. The first American citizen to be proclaimed a saint was Frances Xavier Cabrini, who was canonized in 1946. Mother Cabrini was born in Italy but came to the US in 1889 to help Italian immigrants. Every year, some 80,000 people come to her shrine in New York, where a wax figure lies over some of her remains.

SISTER THOMASINA LANSKI (St. Frances Xavier Cabrini Shrine): She is a person who had many struggles, many faults, many failings, but her life was centered on God.

LAWTON: Sister Thomasina Lanski is administrator of the shrine. She says like all saints Mother Cabrini plays several roles for Catholics.

LANSKI: People actually can come, we have her relic, and they can be blessed by her, and I think it’s important that when people come to pray to Mother Cabrini they’re praying for her intercession. We never worship her. We worship the Lord, and we talk always about prayers through Mother Cabrini to be answered by the Lord. We never say the prayers are answered by Mother Cabrini.

LANSKI: People actually can come, we have her relic, and they can be blessed by her, and I think it’s important that when people come to pray to Mother Cabrini they’re praying for her intercession. We never worship her. We worship the Lord, and we talk always about prayers through Mother Cabrini to be answered by the Lord. We never say the prayers are answered by Mother Cabrini.

LAWTON: Father O’Donnell says the concept of intercession is often misunderstood.

O’DONNELL: The idea of a saint is that he or she is before the throne of God in heaven and that one asks them, you know, to intercede and pray for us. So we’re all praying to God together, because we believe that they are with God. They’re the friends of God, and it’s not bad to talk to some of somebody’s friends, you know?

LAWTON: Are there people who might be saints, but just not recognized?

O’DONNELL: Oh, sure. Oh, my gosh, yeah, yeah, yeah. I could name my own parents, at least my own mother, I don’t think my father would. You meet saints all the time. But they’re never going to be beatified, you know, or canonized. No, there—it is quite amazing how many people live heroic lives. Quietly.

LAWTON: Father Martin says he prays to saints every day. He keeps what he calls his “wall of fame,” with pictures of saints and potential saints.

MARTIN: Some of my favorites are Mother Teresa is here as a real example of working with the poor. Joan of Arc, I think, is someone who is true to her vision. Dorothy Day was an apostle, really, of social justice here in New York. Here’s St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order over there. When I’m sick I pray to St. Bernadette, the visionary of Lourdes. When I pray for humility I pray to Therese of Lisieux. So they each sort of have different roles, as it were, in my life. These are really the ones I look to as my heroes, really, my spiritual heroes.

MARTIN: Some of my favorites are Mother Teresa is here as a real example of working with the poor. Joan of Arc, I think, is someone who is true to her vision. Dorothy Day was an apostle, really, of social justice here in New York. Here’s St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order over there. When I’m sick I pray to St. Bernadette, the visionary of Lourdes. When I pray for humility I pray to Therese of Lisieux. So they each sort of have different roles, as it were, in my life. These are really the ones I look to as my heroes, really, my spiritual heroes.

LAWTON: He says it’s spiritually encouraging to learn that saints were real people.

MARTIN: By putting the saint on a pedestal, sometimes literally, we remove them from our own lives, and we make them less meaningful, and it sort of gets us off the hook. We say, “Let’s leave the tough Christianity to them.”

LAWTON: Martin acknowledges that for some Catholics veneration of the saints can border almost on the superstitious. But he believes a bigger problem is dismissing them altogether. In an era of skepticism and scandal, many Catholics believe saints can help attract people to faith.

O’DONNELL: I find that when I’m preaching or talking in a parish or talking to people in general about this, they’re pretty receptive to saints, even if they’re not so receptive to the hierarchy or a priest or something. The holy person, the holy man, the holy woman—this fascinates people still, and I think it draws them.

O’DONNELL: I find that when I’m preaching or talking in a parish or talking to people in general about this, they’re pretty receptive to saints, even if they’re not so receptive to the hierarchy or a priest or something. The holy person, the holy man, the holy woman—this fascinates people still, and I think it draws them.

LAWTON: And the Church teaches that’s the way it’s been for centuries. I’m Kim Lawton reporting.

BOB ABERNETHY, host: But, Kim, I gather that not everyone is totally enthusiastic about John Paul’s beatification.

LAWTON: There has been some controversy. Advocates for people who were abused by priests say it really sends a bad message for the Church to be beatifying, to be granting honor to someone that presided over the Church at a time when sex abuse crisis was really spiraling. There are questions about what John Paul knew, how much he could have done and didn’t do to prevent the crisis, to punish some of the priests who were involved, and so they’ve raised objections on that grounds. Other people have talked about the timetable. It was a very fast–tracked process, and why not let it take its normal route to sainthood? So there has been some controversy, but the Church says that it’s just responding to the groundswell of support for John Paul II, which is how any sainthood process begins.

ABERNETHY: But that said, there are messages that are sent by who is put on this track and how fast it is.

LAWTON: There are several people who question whether political influence is involved in the process. The fact that some people do seem to get fast-tracked and others—the late Pope John XXIII, who did the Vatican Council, or the slain Archbishop Oscar Romero, very popular as well—but their cases haven’t been fast-tracked, and so there are people who look at that and say, why these guys and not these guys?

ABERNETHY: And John Paul II, when he was pope he presided over a lot of saints.

LAWTON: He loved the saints. He felt they were important for the Church, and so he actually streamlined the process for sainthood when he became pope, and during his almost 27 years as pope he actually canonized almost 500 people and beatified another some 1300, and that’s more than all of his predecessors combined.

ABERNETHY: Kim Lawton, many thanks.