BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Parents want to give their children every advantage in life—music lessons, tutoring, sports camps. They also want to do whatever is possible to make their children healthy. But what about going beyond opportunities and health to enhancement, making kids bigger or smarter or more talented? Science is opening that door in a big way, and many ethicists debate where the line between health and enhancement should be. Kim Lawton has our story.

KIM LAWTON: Twelve-year-old Mitchell Greenwood has a nightly ritual. Before he goes to bed, he gives himself a shot of human growth hormone. Mitchell is healthy, but at 4'1" he's below the normal height for his age.

MITCHELL GREENWOOD: I'm just hoping that I get those couple of inches that I really wanted, that I'm taking it for.

LAWTON: Do some of the kids make fun of you? Are kids mean?

MITCHELL: Yeah. Well, like, some of my friends, they're just like, "Ha, ha, shorty." And I know they they're just joking. But then there are also some people that do it to be mean.

LAWTON: Mitchell is genetically predisposed to be short. His mom, Lisa, is 5'3" and Doug, his dad, is 5'4". Their doctor projected that Mitchell may not get any taller than 5'1" and he suggested human growth hormone might help add two or three more inches to that. They decided to try it.

LISA GREENWOOD: For Mitch, there have already been things in his life that he's wanted to do that he's been unable to do because he's too small. I think that parents will always choose the things that will help their kids grow to be happier, more productive adults.

DOUG GREENWOOD: Some with reason and some without reason, you know. I think this has been a reasonable choice that we've made.

LAWTON: But as biotechnology advances, some ethicists are raising moral concerns about the extent to which parents may try to make even more radical alterations.

Harvard Professor Michael Sandel is a member of the President's Council on Bioethics and author of the new book THE CASE AGAINST PERFECTION. He warns of a slippery slope in the drive toward enhancement.

Professor MICHAEL SANDEL (Department of Government, Harvard University): Aiming at giving our kids a competitive edge in a consumer society—that, in principle, is a goal that is limitless. It has—there is no end. In fact, one can imagine a kind of hormonal arms race, or genetic arms race, whether it's to do with height or IQ, conceivably, in the future.

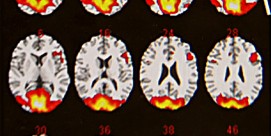

LAWTON: Scientists have mapped human DNA, making it possible to know what genes are responsible for particular illnesses. Clinical trials are now underway to find new treatments for genetically-based diseases. But what if this newfound genetic knowledge is used not only to cure, but also to enhance physical and mental capabilities and to enable parents to select the traits of their children? In 2003, the FDA approved the use of human growth hormone for healthy children who have no defined cause for their short stature.

Dr. PAUL KAPLOWITZ (Pediatric Endocrinologist, Children's National Medical Center): The decision was controversial because there were a lot of people who felt that this was cosmetic treatment—like why take a normal child and put them on a medication that their body is probably making some of anyway just in order to make them grow taller?

LAWTON: Paul Kaplowitz is the pediatric endocrinologist treating Mitchell Greenwood. Although some of his colleagues treat normal height children who want to be taller, Kaplowitz says he would not.

Dr. KAPLOWITZ: If I see those children I simply say, "You know, this is not an appropriate use of growth hormone. Your child may be shorter than you would like, but they're fine. They will reach a normal height." And furthermore, I tell them that, you know, if we insist on treating them, we are sending them the message that there is something wrong with them. They are not okay the way they are.

LAWTON: Sandel says he does support the use of new biotechnologies to cure illness.

Prof. SANDEL: My argument is not that we must never intervene in nature. My argument is that there is a moral difference between intervention for the sake of health to cure or prevent disease, and intervention for the sake of achieving a competitive edge for our kids.

LAWTON: But according to UCLA professor Gregory Stock, author of the book REDESIGNING HUMANS, the line between therapy and enhancement is never clear-cut.

Professor GREGORY STOCK (Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavior, UCLA): Any time there is a reduction in some disease process, in some affliction which we can all support, the possibility exists of other enhancements, and I see this as a very robust development. I don't see that we're moving toward some sort of a cliff.

LAWTON: Few people think twice about getting their kids braces, but what about genetic help to boost their memory? Stock's company, Signum Biosciences, is researching therapies for Alzheimer's patients. He's not concerned that parents might also use that therapy to help their children do better in school.

Prof. STOCK: If we could enhance our memories, to me that superficially seems desirable. It's not clear that it would be of as much value as we want, or that it's as necessary since we have all sorts of electronic devices that are essentially memory enhancers.

LAWTON: Technologies are also moving forward that may one day allow parents to pre-select various traits, including personality or temperament. In Scarsdale, New York, Dr. Andrew Silverman is already helping parents choose the gender of their children. Most couples come to him for family balancing. Silverman is Jewish and says he initially did have ethical concerns, until he consulted with a rabbi.

Dr. ANDREW SILVERMAN (The Silverman Center for Gender Selection): He says he doesn't see a problem. He said, "You are helping couples procreate. You're not destroying life, you are creating life. You are a partner with God. Go ahead."

LAWTON: Still, Silverman says he would draw a moral line at helping parents pick other qualities, such as personality.

Dr. SILVERMAN: I'm sure there'll be other professionals who will. If it's available and it's not illegal, people will offer it. You know, the greatest joy and mystery of life is seeing how your kids turn out, because they are in the same home environment. They have relatively the same genetic spread, assuming it's the same marriage. Then how they turn out is the wonderment of life.

LAWTON: Professor Sandel opposes sex selection because he believes it changes the parent-child relationship.

Prof. SANDEL: The norm of unconditional parental love, I think, depends on the fact that we don't pick and choose the traits of our children in the way that we pick and choose the features of a car we might order.

Prof. STOCK: Is it the child that is being damaged by being the gender of choice of that parent? I don't think so. Who is being injured if parents have a predilection for certain types of personality and temperament, if they would be more comfortable or think they really would prefer to have a child who's a little more outgoing, or who's more introverted, or who is a little brighter?

LAWTON: Stock believes there is a moral responsibility to push forward with research, trusting that human beings have a great capacity for adapting to technology.

Prof. STOCK: So, you know, where is this going to lead us? We don't really know. And to sort of be engaged in this process, which is changing the world around us, which is, you know, changing ourselves, which is life beginning to get control of its own processes and to act upon that information, and to me it's awe-inspiring.

LAWTON: Such power is precisely what worries Sandel.

Prof. SANDEL: In most of our lives, we are accustomed to aiming at mastery and control and dominion—over Nature, over our lives, over our jobs, over our careers, over the goods that we buy. But parenthood is a school for humility.

LAWTON: And there are larger social questions, such as cost.

Dr. KAPLOWITZ: A course of growth hormone to add an extra couple of inches could easily get close to $100,000, and the question is who is paying for this? Well, in most situations the insurance companies are paying for this.

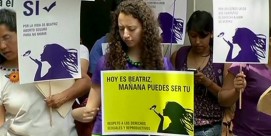

LAWTON: Some worry about the creation of two very separate classes of people: those who can afford genetic enhancements and those who cannot.

Prof. SANDEL: It will only deepen the gap between rich and poor and possibly inscribe that gap in our biology.

LAWTON: Already, many parents compete to give their children every possible advantage. There are tutoring and private coaching lessons. Would they consider genetic enhancements as well?

WENDY: If there was a drug or something that people had, and it was like they could prove that it wasn't harmful, I don't know how people would react. I mean, we can all say we wouldn't do those things, but it's hard to say.

GREG: If you found out there was possibilities you haven't thought of, and the research was done to make it safe, but then you might end up with the Bionic Man or Wonder Woman or something like that. I don't think that would be right.

MARA: I just think that you don't play God.

LAWTON: For Doug and Lisa Greenwood, it came down to doing what they thought was physically and emotionally best for Mitchell.

Ms. GREENWOOD: I think it's easy to have this debate when it is just a debate that you're having. But when you are faced with, well, your child could be 5'1" or maybe he will be 5'5" or 5'6" you are going to choose 5'5" or 5'6".

Mr. GREENWOOD: You want to give your kids the very, very best so they can have opportunities that you haven't had in education. And growth is certainly one of them—and health.

LAWTON: With new technological breakthroughs, those decisions will only get more complicated in the years to come, and society will have to grapple with what should be allowed. I'm Kim Lawton reporting.