The Ethics of Sanctions

by David E. Anderson

On July 1, President Obama signed legislation imposing new unilateral sanctions on Iran that he promised would “strik[e] at the heart of the Iranian government’s ability to fund and develop its nuclear program.”

“We’re showing the Iranian government that its actions have consequences,” Obama said. “And if it persists, the pressure will continue to mount, and its isolation will continue to deepen. There should be no doubt—the United States and the international community are determined to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.”

At the same time, Obama suggested that the United States and the international community have learned something from the morally disastrous sanctions imposed on Iraq two decades ago, resulting in a humanitarian catastrophe that left the civilian population devastated, the infrastructure in tatters, and hundreds of thousands of children dead.

The new Iranian sanctions, Obama said, would be targeted or “smart” sanctions, aimed at the elite and those “who commit serious human rights abuses,” while exempting technologies “that allow the Iranian people to access information and communicate freely.”

Obama also insisted that “the door to diplomacy remains open. But there is no new diplomatic initiative in the offing, according to Robert Kagan, a prominent neoconservative scholar and foreign policy commentator who attended a White House briefing on the Iran sanctions this summer. Kagan wrote in the Washington Post that the White House believes the new sanctions against Iran “would at least cause the regime significant pain,” but at the same time the president acknowledged “that the regime may be so ‘ideologically’ committed to getting a bomb that no amount of pain would make a difference.”

The sanctions bill passed Congress overwhelmingly, 99-0 in the Senate and 408-8 in the House, with not a lot of debate on Capitol Hill and little discussion outside the halls of Congress. It was welcomed by the roughly 50 members of the conservative group Christian Leaders for a Nuclear-free Iran, while a number of policy analysts voiced their misgivings. The unilateral US sanctions, accompanied by a similar set of unilateral measures from the European Union and Asian nations, followed a fourth round of United Nations-imposed punishments—its harshest sanctions yet against Iran—that were approved by the Security Council on June 9. Yet in early September the New York Times was reporting that, despite sanctions, Iran “has dug in its heels, refusing to provide inspectors with the information and access they need to determine whether the real purpose of Tehran’s program is to produce weapons.” So far, at least, sanctions have not forced Iran to change its direction.

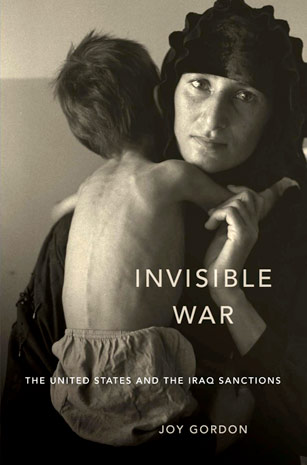

The tough new measures on Iran coincide with the publication of “Invisible War: The United States and the Iraq Sanctions” (Harvard University Press), a comprehensive and devastating look at the sanctions imposed on Iraq in 1990 and kept in place until the 2003 invasion by the United States and its allies in what was called “the coalition of the willing.” The author is Joy Gordon, professor of philosophy at Fairfield University and a prominent voice for many years in debates over the ethics and morality of using economic sanctions in international public policy.

“Invisible War” is a harsh moral and practical judgment on the role the US played in imposing sanctions on Iraq, and it sounds a timely ethical warning about the future use—and misuse—of sanctions. Gordon writes:

The sanctions regime on Iraq, as it was designed, interpreted, and enforced by the United States, evinced a willingness to see appalling things done in the name of security, and this requires us to consider that measures equally damaging and indiscriminate may be pursued in other circumstances, whether in the name of stopping aggression, drug trafficking, or terrorism. We must come to grips with the perversity of this. It is simply not good enough to say that atrocities committed for the right reasons, or by respected international organizations, are not really atrocities after all.

She states the case even more strongly in a recent post on one of the blogs of the Web site of Foreign Policy magazine:

It is hard to look at the current sanctions on Gaza and Iran without recalling the Iraq sanctions regime—both the structural damage and pettiness. It seems that what the US learned from Iraq was to claim that it now employs “smart sanctions,” which will never do the kind of broad damage as we saw in Iraq. As we hear that Israel will now allow potato chips and juice into Gaza, it is hard to fathom how anyone can rationalize that these ever posed a threat to Israel’s security. But above all, what we should know from Iraq is this: causing destitution in distant lands does not make the world a better place, or make the United States, or anyone else, more secure.

In the last decades of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first, as the Cold War ended and new forms of international conflict arose, sanctions emerged as a major tool of foreign policy and international governance, and one that has been employed especially by the United States, acting either with the United Nations or with allies or unilaterally. As Gordon and others have pointed out, more than two-thirds of the 60-plus sanctions cases since 1945 were initiated by the United States, and three-quarters of those involved unilateral US actions. Writing on ethical economic sanctions 10 years ago in the Jesuit magazine America, David Cortright and George A. Lopez of the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame declared, “Sanctions have become the virtual 911 of international decision makers to enforce norms of justice and international peace.”

Sanctions are attractive to policy makers—and the public—for a number of reasons. They seem more substantial than diplomatic finger-wagging, less costly to impose than military action, and morally preferable to war. “They are often discussed as though they were a mild sort of punishment, not an act of aggression of the kind that has actual human costs,” Gordon wrote in a 1999 issue of CrossCurrents, the journal of Association for Religion and Intellectual Life.

Over the years, as the humanitarian consequences and punitive social impact of comprehensive economic sanctions imposed on Iraq and other countries such as Haiti, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Yugoslavia became apparent, ethicists began debating more urgently how this tool should be understood. Albert C. Pierce, professor of ethics and national security at the National Defense University in Washington, DC, writing in a 1996 issue of Ethics & International Affairs, the journal of the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, argued that economic sanctions “are intended to inflict great human suffering, pain, harm, and even death and thus should be subject to the same kind of careful moral and ethical scrutiny given to the use of military force before it is chosen as a means to achieve national political objectives.” According to Gordon, “because sanctions are themselves a form of violence, they cannot legitimately be seen merely as a peacekeeping device, or as a tool for enforcing international law…They require the same level of justification as other acts of warfare.”

Pierce, Gordon, and others say sanctions should be evaluated in much the same way and with similar principles as force is evaluated, that is, with the just war doctrine. Gordon, for example, argues the sanctions imposed on Iraq violated both the criteria that must be met before going to war, such as just cause and the probability of success, and the criteria for how the war is conducted, employing such norms as proportionality and discrimination,’ which bars directly intended attacks on noncombatants and noncombatant targets.

Comprehensive economic sanctions as employed against nations such as Iraq in 1990, Haiti in 1991, and Cuba since the 1960s, have failed to achieve their goals while at the same imposing devastating hardships on the civilian population. Gordon cites studies that found the economic sanctions leveled against Iraq were responsible for the death of some 237,000 Iraqi children under age five. At best, sanctions have been successful in just a third of the cases where they have been employed. US sanctions in Iraq “systemically overrode many of the basic principles of international humanitarian law,” she writes, adding that “many have maintained that the magnitude of the suffering was such that the sanctions regime could properly be termed genocidal.”

Some experts, however, pointing to the cases of South Africa and Yugoslavia, suggest there have been at least modest successes with the use of the sanctions tool. “Even in Iraq,” according to Cortright and Lopez, “where the frustrations and humanitarian agony of sanctions are most acutely evident, sanctions initially had some impact in convincing Baghdad to make concessions to UN demands.” They argue that sanctions can be reformed, and smart sanctions can be used to deny decision-making elites access to financial resources while trying to avoid harm to civilian populations, thus meeting moral and ethical standards.

They have also written that “some degree of civilian pain is inevitable with the application of sanctions and does not make every use of the instrument unjust. International law professor Lori Fisler Damrosch argues that, although sanctions impose hardships on vulnerable populations, they may be ethically justifiable if carried out for a higher political and moral purpose such as halting aggression or preventing repression.”

Cortright and Lopez have suggested that “the use of targeted measures, if properly enforced, could be a means of enhancing the effectiveness of sanctions while reducing their adverse humanitarian consequences.” They caution that “substantial improvements in international compliance will be necessary, however, for financial sanctions, arms embargoes, and travel sanctions to have the kind of targeted impact reformers seek.”

In particular, they argue that “sanctions work best as instruments of persuasion, not punishment,” and concessions by a targeted regime “should be rewarded with an easing of coercive pressure.” Even the imposition of smart sanctions “should be limited by specific ethical standards of just cause, last resort, right authority, probability of success, proportionality, and civilian immunity.”

Applying just war criteria allows for making some distinctions. Lopez, for example, has endorsed the most recent round of United Nations sanctions against Iran, arguing they have a reasonable chance of success. He has also noted they “capture the important policy subtlety that sanctions must pressure for compliance, not punish for capitulation,” are smart in that they “undermine real assets and capabilities that Iran might use for weapons production,” and make sanctions “the cornerstone rather than the entire edifice of a nuclear rollback policy.”

But Lopez has been critical of the unilateral US sanctions, testifying before Congress in December the proposed unilateral step by the US “will inflict economic pain in Iran, but produce no political gain on issues important to the United States.” They would have, he said, an adverse impact on the human rights situation in Iran, strengthen the ruling regime, and would undermine “the reasonably strong coalition of support condemning Iranian actions that has emerged over the past year, and which is the ultimate leverage against Iranian misbehavior.”

Looking at past examples of where sanctions-stimulated reversals have occurred—Ukraine, South Africa, Brazil, or Libya—Lopez said the lesson for the Iranian case is “we cannot punish them into a nuclear deal.”

“Only an astute mix of narrow sanctions to focus their attention, continued engagement, and versatile incentives will provide this,” he told the House Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs.

Meghan L. O’Sullivan, a professor of international affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, gives the current sanctions regime “good marks in terms of being well-structured in relation to the goals,” and she praises the Obama administration for its effort to “standardize the message about the goal of sanctions: to coerce Iran back to meaningful negotiations—not to destabilize the regime.”

Yet as she has argued in an online interview with Bernard Gwertzman of the Council on Foreign Relations, if the sanctions are to have “any hope of bringing Iran to the table in a meaningful way, they need to be perceived by Tehran as a serious threat to regime stability. And that would involve some real stress on the Iranian economy such as major inflation, growing unemployment, unrest over economic circumstances.”

But that pushes the situation toward the ethically questionable outcome of inflicting harm on civilians rather than regime leaders and raises inevitable questions about the relation between sanctions and force. For Gordon, sanctions themselves are “a form of violence—no less than guns and bombs—and it is ethically imperative that we see it as precisely that.” For Patrick Clawson, who directs the Iran Security Initiative at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “If there is no will to use force to back the sanctions, then the sanctions are morally dubious.”

In March, Richard Land, president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and a member of Christian Leaders for a Nuclear-free Iran, called Iran “the most dangerous regime in the world” and said “the diplomatic virtues of patience must not be used to conceal the vices of inaction and appeasement.”

The conservative leaders, who include Chuck Colson of Prison Fellowship, Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council, Bill Donohue of Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, and Pat Robertson of the Christian Broadcasting Network, among others, did not address any ethical issues but focused on the danger of a nuclear-armed Iran.

“We are running out of time to apply diplomatic pressures to this dangerous regime, and every day we delay, every moment we fail to show resolve, that regime comes closer to threatening the region and stability of the world with nuclear weapons,” the group said in June.

Nor have more liberal religious organizations broached the Iran sanctions issue with ethical analysis. In its most recent statement, the World Council of Churches warned in 2007 that “threats to begin another war in the Middle East defy the lessons of both history and ethics.” The council said it was referring to “the belligerent stance of the US toward Iran and of Iranian threats against the US and Israel. The region and its people must not suffer another war, let alone one that is unlawful, immoral, and ill-conceived once again.”

The lack of particular religious and ethical response to the latest round of sanctions against Iran may be due in part to the fact that so far the sanctions are targeted rather than comprehensive, aimed Revolutionary Guard-owned businesses, Iran’s shipping industry, and the country’s commercial and financial sector.

But the US sanctions also target Iran’s energy sector. The July unilateral sanctions penalize companies for selling refined gasoline to Iran or supplying equipment in a bid to increase its refining capacity. Despite being a major oil producer, Iran imports at least a third of the refined gasoline products it needs and, if tightly enforced, sanctions could bring about widespread disruption of the Iranian economy. Some policy experts worry, however, that such secondary sanctions—targeting firms that do business with Iran—inadvertently do more harm than good.

“They are sanctions against our allies, and the people that we need to get on board with us, to help us deal with them,” Kimberly Ann Elliott, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, said in an online interview with the Council on Foreign Relations.

Robert Einhorn, the State Department official who oversees US sanctions against Iran and North Korea, told National Public Radio on Sept. 1 the sanctions are beginning to work—at least to put pressure on the government if not to bring it to the bargaining table.

“It’s interesting to know that Iran’s imports of gasoline have dropped very substantially in recent months,” he said, “so that is putting pressure on Iran.”

At the moment, however, nobody is raising moral and humanitarian concerns about either sanctions imposed by the United Nations with a general international consensus or the more stringent measures imposed unilaterally by the United States and the European Union. But sanctions create an ethical conundrum. If smart sanctions do not appear to be working, if they do not have the right combination of pain and incentives to induce a regime to come to the bargaining table, if they are seen, in just war terms, as unlikely to produce success, then the temptation for policymakers is either to abandon them for another alternative, usually armed force, or to ratchet up the penalties closer to the punishing comprehensive embargo imposed to such devastating effect—Gordon calls it “gratuitous harm”—on the Iraqi people.

Either move entails the risk of violating just war principles. But a choice in one direction or the other might at least generate a more robust public conversation about the ethical justifications and moral implications of economic measures designed as an alternative to war, and more vigorous debate about the proper policy toward Iran—a debate that has yet to take place.

David E. Anderson, senior editor at Religion News Service, has written most recently for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on “Drones and the Ethics of War.”